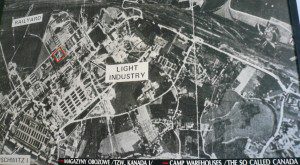

Seventy years ago, Hitler and his henchmen murdered civilian populations across occupied Europe: Jews, Roma, homosexuals, communists and thousands of other so-called enemies of the Third Reich. But before they did, they stripped them of every single personal possession – from heirlooms to clothing to gold fillings – and stockpiled them for exploitation by the Nazi regime. In an ironic twist of fate, I learned recently, the warehouses at Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp had an odd nickname.

“The Polish prisoners called the warehouses ‘Canada,’” our guide at the concentration camp museum told us, “after the faraway place they’d once heard contained riches and freedom.”

It’s true. Even though virtually none of those imprisoned in those Second World War extermination camps of Eastern Europe would ever have travelled to or seen a real picture of the northern half the North America, they chose to call the place that stockpiled their stolen belongings, “Canada.” The Canada warehouses became the destination of all they had ever owned. In a sense, the Canada warehouses became prisons of their identity.

As many Canadians have learned when they travel aboard, it’s often outside the country that Canadians discover the strengths and benefits of citizenship here. In fact, during another stop in the Czech Republic, last week, I had lunch with our personal tour guide.

As we dined on a Czech borsht and bread, Veronika Smidova commented about the nature of the people in the tours she guides. In particular, she couldn’t get over the groups from the U.S. Since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, she said, the Americans didn’t seem to want to trust anyone; she said they even wanted all restaurant foods checked for quality and safety.

“They wanted to know if I carried a first-aid kit in case the tour was attacked,” she said.

On the other hand, she pointed out that Canadians were so accommodating, so interested in experimenting and never demanding. “They even apologized for not knowing as much Czech as I knew English.”

Our Czech guide wasn’t so much painting a picture of the mythical “ugly American,” as she was paying tribute to some of the qualities that Canadians exhibit both at home and away. Because Canada is a nation of immigrants, the culture, language, culinary traditions and customs of so many Canadian communities have become as diverse as the people who live there. The presence of different foods, accents and even diverse attitudes has become the norm, not the exception.

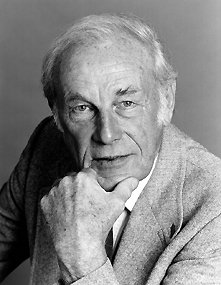

I can recall producing a series of broadcasts about Toronto’s multi-cultural makeup back in about 1970. Among my subjects was Czech-born opera singer, broadcaster and actor Jan Rubes, who earned international acclaim in such films as “Witness,” “Dead of Winter” and “The Outside Chance of Maximilian Glick.” At that time, before his eventual stardom, we met at his favourite Czech restaurant on Eglinton Avenue just east of Bathurst. He introduced me to his ethnic foods and regaled me with tales of his immigration to Canada and his struggle to act in his second language, English.

“The first couple of performances,” Rubes said back then, “I didn’t know how the audiences could hear through my heavy Czech accent.”

Years later when we met again in Collingwood, Ont., I asked him what he was most proud of during his lifetime. I thought he might mention a favourite opera he’d sung, one of his many CBC radio broadcasts or certainly one of his 40 films.

“No,” he said, “I’m most proud of being a Canadian.”

In addition to introducing me to the “Canada” warehouses of Auschwitz concentration camp, my recent tour of Eastern Europe also took our tour group to the place where, in many ways, the Holocaust began. Early in 1942, when Hitler’s hatchet men gathered to plan the reshaping Europe in their own Aryan image, they assembled at the villa of a former German industrialist. The meeting to decide who would do what to whom – otherwise known as “the final solution” – became known as the Wannsee Conference. In just 90 minutes, our German guide informed us, this elite group of 15 Nazi bureaucrats determined the fate of millions based on their skin colour, ethnic origin or religion.

As an aside during that part of his talk, our guide – a PhD student named Jakob Mueller – paused and noted what he knew about Canada’s religious makeup.

“Catholic, right?” he asked rhetorically.

“No,” I said. As he looked back at me in surprise, I added, “Canada has the most diverse population anywhere and welcomes the practicing of every religion in the world.” He seemed embarrassed by his own naïve assumption. When we chatted later he still seemed surprised, as if to say, “How could they all practise their different faiths together in one place?”

Well, I said, it has not been easy or accomplished overnight. But I suggested, unlike nations of the Old World and even those in the Developing World, Canada’s very founding (the British North America Act of 1867) and its recent update (the patriated Canadian Constitution of 1982) have enshrined such things as the right to practise one’s religion, speak one’s mother tongue and wear one’s indigenous clothing (including religious garb) from coast to coast to coast.

I repeated that the Canadian experiment was not yet a complete success. But, I emphasized, we try to accommodate where others steadfastly refuse. Their millennia of feuding and fighting have proven our experiment has merit.

Sometimes, the qualities and strengths of being Canadian are not as obvious as hockey prowess, the Rocky Mountains or maple syrup. Sometimes, they are the subtleties of tolerance, personal pride of citizenship and our celebration of our global roots.

Yes, I winced when I stood in front of the pictures of the “Canada” warehouses at Auschwitz. But during these same Eastern European travels, when I listened to the way others talked about the personality of this country and its people, I also realized the values we hold strong, the ones that set us apart, are the ones that make for a deeper celebration than just waving a flag, singing an anthem or setting off fireworks. They are the ones worth celebrating.

What makes Canada Canada is very often the way the world sees us.

Last night, I had dinner with a guy whose grandmother as a Polish Jew who was sent to the Canada warehouse – she worked in the linens department. We were amazed and disbelieving. He said she didn’t like talking about it and as children they thought she meant Canada, North America. Yours, Deborah.