Just before I delivered a Remembrance talk in the southwestern community of Shedden, Ont., last Sunday morning, I walked along the back wall of the Southwold Township Complex, where I was to speak. There were perhaps 500 people waiting for the township’s annual pre-Remembrance Day observance to begin.

And standing politely along that back wall, so that older citizens – principally veterans and their spouses – could have seats, were about 20 young army and air cadets. I made a point of introducing myself to them and learning who they were before I spoke.

“I’m 18 and in the Elgin Regiment,” one of them announced proudly.

“And why did you offer your part-time service?” I asked.

“I wanted to say something about my generation,” he said.

I can’t tell you how much inspiration those young part-time soldiers gave me that day. I wished I could have bottled their positive attitude and given some of it to those young people who vandalized the First World War memorial at Toronto’s Malvern Collegiate the same Sunday. That might have gone further than all the outrage from politicians, school officials and the public, we heard about on Monday.

Yes, I was offended by the damaged monument too. But louder outrage, more video surveillance and stiffer jail sentences, as some called for, I don’t think would solve the problem. I suggest that the tact I took during my Sunday talk in Shedden might go a bit further toward bringing the vandals around.

“Don’t think of the people who served Canada in past wars as the older, greying senior citizens you see seated here in the hall,” I told the young cadets at the back of the hall. “Think of them as the young person you see in the mirror.”

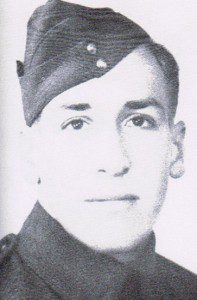

I told them to think of that image of themselves as they looked at a picture I projected of Fred Barnard and his Don Barnard the morning they – barely beyond their teens – stormed ashore at Juno Beach with the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada. I told them to imagine the two of them receiving their baptism of fire the same day – D-Day, June 6, 1944 – as the Allies broke through Hitler’s Atlantic Wall to begin the liberation of Europe. And I told them to imagine that one of them wouldn’t make it past the first day.

“I saw my brother Don … lying on his back as if he was asleep,” Fred Barnard said. “There was just a black hole in his uniform right in the middle of his chest. No blood. He must have died instantly.”

I told one of the young women cadets not to consider images of their aging grandmothers when they looked back at the pictures and heard stories of women in wartime. No. I asked them to consider a picture of Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service volunteer Ronnie Egan.

At 19, Ronnie had left her family in Vancouver, joined the Royal Canadian Navy to serve her country where she could, and become a chief petty officer heading up the clerical staff at HMCS Stadacona in Halifax, N.S. during the war.

“As far as my experience in the Navy goes,” she told me, “we were treated well. We had clean sheets, good blankets, excellent meals and good living quarters… It was a case of joining up, doing my share.”

Then, I presented the image of a Canadian whose war was nearly forgotten by the government, the military, the media and the public. That was Bud Doucette’s war. Born in Montreal in 1932, Bud had responded to a call for volunteers to sign up in a United Nations special force in 1950 to defend the borders of South Korea (breached by the Communist North Koreans that year).

Eventually, as a trained machine-gunner in the Royal Canadian Regiment he was shipped to the Far East and served 121 days along the front-lines where everyday the Chinese Communist Forces bombarded their positions relentlessly.

“When the enemy opened up,” he said, “you couldn’t hear yourself think.”

Again, I reminded the young people in the audience not to think of these events as “ancient history” or as “old people’s wars.” I pointed out that it was the 17- and 18- and 19-year-olds who had liberated Normandy in 1944, done essential service on the homefront throughout the Second World War, and defended the United Nations peace charter in Korea between 1950 and 1953 all because their country expected that of young men and women in the armed services.

Just the same as that young cadet in Southwold Township last Sunday, Fred and Ronnie and Bud (whether they put it in those words or not) “wanted to say something about my generation.”

What could be a better model for young people than to make that kind of statement for their country or themselves?

Hi Ted

In 2009 I took a trip with you to Juno Beach (the 65th anniversary). I am wondering if you have any more trips planned over there as I have a friend who would like to come with me to see this area.

Sincerely

Don Lockhart