About 25 years ago, I travelled to the town of Windsor, in the Annapolis Valley region of Nova Scotia. I’d read about a local personality, a 19th century judge and member of the provincial legislature, Thomas Chandler Haliburton. Among other things, I’d learned that Haliburton had studied and grown up there, written local history and published under the nom de plume “Sam Slick.” But Haliburton had also kept a factual diary, which around 1803 had solved the great Canadian riddle: Where was the game of hockey first played in Canada?

“And boys let out racin’, yelpin’ hollerin’ and whoopin’ like mad with pleasure (on) the playground,” Haliburton had written as a student at King’s College, Windsor, “and (played) the game of hurley … on the ice.”

My world of writing depends largely on the hunt for facts. It’s based on the principles of research, discovery and verification. Had there not been a source for Judge Haliburton’s revelation, I would never have learned about the birthplace of hockey, nor included that story in my book “Playing Overtime.” My discovery very much depended on the facts as gathered by a local museum and a local neuro-surgeon and recreational hockey enthusiast named Garth Vaughan. The good doctor’s Windsor Hockey Heritage Society and the museum he founded had delivered to me the details of hockey played on Long Pond, in Nova Scotia, 200 years ago.

A number of us this week were wondering what we might do if we came into some great wealth – say $1 million. Well, as I say, I would probably bestow much of it upon museums such as this. Why? Principally because local museums and their artifacts represent the unofficial, but crucial foundation of Canada’s story. When fledgling communities took root in Nova Scotia and elsewhere in this country, there were no official recorders of events, no provincial archives, few newspapers or journalists.

The documenting of Canada’s history depended on handed down stories, folklore, diaries and local museums. They receive little or no official funding. They survive purely on volunteer contributions of dollars and hours. They survive on the goodwill of communities. That gift, I suggest, ought to be rewarded.

Another chunk of my $1 million bequest might be to a small repository of local history in Saskatchewan. About a dozen kilometres outside the City of Moose Jaw, sits a 10-acre piece of prairie land that houses a pioneer museum. The land, and many of the pioneer implements, buildings and artifacts, were donated by long-time farmer and local historian Erald Jones. I met him in the early 1970s while researching a book about prairie steamboats.

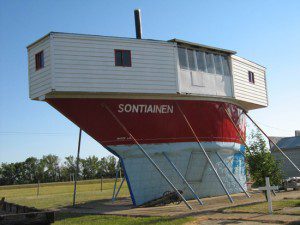

Steamboats on the prairies? That’s right. Between 1859 and the mid-1950s, there were as many as 125 different steam-powered vessels plying the lakes and rivers of Saskatchewan. Among the boats’ human builders was a Finnish immigrant named Tom Sukanen, whose story I learned from Jones and his museum pals. Briefly, during the Depression, pioneer Sukanen lost nearly everything – his family, his crops, his desire to stay on the prairies. He concocted a plan to build a steamship in pieces, transport it via the Saskatchewan River to Hudson Bay and sail home to Finland. Sukanen’s bizarre story became a chapter in my 1977 book “Fire Canoe,” thanks to the Sukanen Ship Pioneer Village Museum. The completed Sukanen ship stands today like a sentinel just outside Moose Jaw.

Perhaps another portion of any sudden $1 million bank account might go to the modest Elgin Military Museum in St. Thomas, Ont. Named after the fabled Elgin (Armoured) Regiment, whose honours in the Second World War include battlefields in Sicily, Italy and North-West Europe, the museum began in 1975. Not surprisingly it has assembled representative weaponry and souvenirs of those campaigns. But its members have consistently pursued history outside the box. Currently, museum volunteers have plans to salvage Royal Canadian Navy submarine, HMCS Ojibwa, and bring it to landlocked St. Thomas.

My research and writing changed when collector friend Blair Ferguson and the Elgin Military Museum gave me access to its human collection. In 2005, as I assembled my book “Victory at Vimy,” I learned the museum had recently acquired the letters home of Victoria Cross winner Ellis Sifton. With the museum’s permission, I was able to flesh out an otherwise clinical history of the man. In his final letter home to his sisters in Wallacetown, Ont., for example, Sifton wrote about the greatest challenge of the coming Vimy battle.

“(I wonder whether) courage will be mine at the right moment if I am called upon to stare death in the face,” Sifton wrote just before April 9, 1917. His VC proved it was. But only the local museum in St. Thomas had known his human condition at the time.

So if I won that elusive $1 million, I’d almost certainly help the greatest friends a non-fiction writer has, the keepers of a community’s heart and history.