The other night just before I gave a presentation to a historical group in north Toronto, a number of people with the volunteer organization were recognized for their service. In particular, the group recognized a woman who had served the Richmond Hill Historical Society as its secretary.

“Mrs. Monkman is leaving her position,” the president said, “after 26 years of service to the society.”

It took a couple of seconds to sink in, but as I joined the brisk applause directed her way, I thought how remarkable that she had kept the books, recorded the monthly meetings and documented the society’s history so loyally. And for so long! Twenty-six years, I thought. That’s a third of a lifetime, longer than most marriages last these days, almost a full generation. I applauded all the more vigourously for her longevity in the job as much as her efficiency in it.

Working in one place, remaining loyal to an employer, being a so-called “lifer” in one job, used to be the rule, not the exception. But these days, when neither employers nor employees expect working relationships to last more than the length of a contract, I find it remarkable when I come across people such as Mrs. Monkman. Granted, hers was a volunteer service, not a paying one. Even so, I think that sort of commitment is rare.

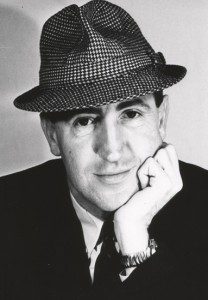

I think of Alex Barris, my own father, for example. He came to Toronto from New York after the Second World War. In 1948, he took a job as a general assignment reporter with the Globe and Mail and remained with the newspaper for about eight years before jumping (with his managing editor John D. MacFarlane) to the Toronto Telegram. At the time, his leap to the rival newspaper was considered remarkable, unexpected, almost disloyal.

But as it turned out, since my father soon became a freelance writer (working on contract for print and electronic media) for the rest of his life, his changing newspapers simply reflected his desire to try something new. In the late 1960s, he even jumped the country. He went to Los Angeles to try his hand, as many Canadian writers did then, at writing sit-coms for U.S. TV.

“Hollywood on five promises a day,” my father later described it.

Some of my father’s contemporaries shook their heads at his daring. Why leave a paying job with a recognized firm? Why leave security for uncertainty? Unlike my father, the men and women who asked him that were lifelong employees. They craved work with Bell Canada, Procter and Gamble, General Motors, heck, even the civil service. Get a government job, they suggested, and you’re sitting pretty. Well, in more than just his choice of working lifestyle, my father was a maverick.

Not surprisingly, I chose much the same path. While over the 40-or-so years I have been a professional writer I have worked “on staff” in a few places, I have mostly written, broadcast or authored alone and without a net. I have preferred the variety and the opportunity associated with a freelance life.

Thus far, I have managed the risk. I admit that it’s probably been a test for my marriage, often tougher on my family and occasionally the cause of sleepless nights. But above all I have enjoyed the freedom. Whenever people have queried me I’ve generally resorted to another of my father’s witticisms.

“I just can’t seem to hold down a steady job,” he used to say with tongue firmly planted in cheek.

That aside, I still admire my peers who have chosen the opposite. I know many men and women who have remained with the same company, school board, civil service, or volunteer organization – much like Mrs. Monkman – for a generation. That, in a society that seems to have lost its sense priorities, most of all for loyalty, I believe is unique and laudable.

And speaking of paying tributes, earlier this fall the college where I teach sent me an invitation. It requested I be present during Centennial College’s annual kick-off for the fall term. The reason it especially wanted me there was that I was to be recognized among a number of professors. I had forgotten, but apparently I have been teaching at the community college for a significant time and the institution wanted to acknowledge my service.

“Congratulations on receiving your 10-year service pin,” the letter said.

And I wondered what my father would have thought. I wondered whether he’d have considered me a sell-out. My guess is he would have been just as pragmatic as I was 10 years ago to take the position offered. At the time, a staff teaching position seemed to fit my lifestyle. Even so, I’ve never really considered myself “tenured” because these days even being “on staff” is a temporary phenomenon.

Nothing is forever anymore, least of all a permanent job.