The morning the world changed, I had tumbled from my warm bed, found a cup of coffee to help me on my way and driven from the countryside to the old CBC Radio building on Jarvis Street, next to CBC corporate head offices in downtown Toronto. By 5 a.m. I had cleared my head and my throat to deliver one of my first newscasts for the CBC Network that morning. Little did I know within the first hours of my shift, I would be part of something momentous.

“Here is the CBC News,” I said at the top of each hour that morning to begin the five-minute hourly newscast. But that day I also got the chance to announce repeatedly as the top story, “Nelson Mandela, the black African leader imprisoned for treason since 1963, has this morning left notorious Robben Island prison, a free man.”

It was Feb. 11, 1990. And that Sunday morning, what particularly South Africans thought was unlikely, if not impossible, had occurred. The man who had studied in a school system for blacks only, who had struggled for black liberation, who had helped form the youth wing of the African National Congress campaigning non-violently to end the racial segregation of white and black South African society (apartheid), and who had been arrested, tried for treason and tossed into the prison on Robben Island for life, had been released.

On that Sunday morning, then 72, his hair graying, his frame erect but worn, Nelson Mandela stepped onto the steps of the city hall building in Cape Town, South Africa, and began to reshape a people and a build a nation.

“I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination,” he said in that speech (quoting words he had used in his own trial defence in 1963). “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society, in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.”

And we had witnessed all this that morning in the CBC Radio building next to those Crown corporation offices we ironically called “The Kremlin.”

What’s remarkable, given that analogy, is that Nelson Mandela changed South Africa faster and more thoroughly than perhaps any modern nation. How long had it taken the United States, for example, to grant civil rights to its black population? Almost exactly a century.

When did the Canadian government get around to apologizing for its Residential School policy of segregating First Nations youth? More than a century after the first treaties were signed between Queen Victoria and the aboriginal peoples in Canada. Modern democracies learned a great deal from the man who walked from that South African prison in February 1990.

“Negotiations on the dismantling of apartheid will have to address the over-whelming demand of our people for a democratic, non-racial and unitary South Africa,” he said that day. And negotiate he did, with that characteristic non-violent philosophy that had served him so well those 28 years in prison.

Within a few years of Mandela’s release, he had transformed his ANC not only into a powerful political force of change, but also into a government in waiting. He had challenged his jailers, the white government of F.W. de Klerk, to deconstruct apartheid and give its blessing to free elections, regardless of skin colour, political stripe or station in life.

The transition to democracy did not avoid the setbacks of violence and resentment from many quarters, but within a decade of his release, by 1997, Mandela had formed a multi-racial government, introduced massive social reform and earned world notoriety for his brilliance – winning the Nobel Peace Prize (for himself and de Klerk). Few in the so-called Western Democracies can make that claim.

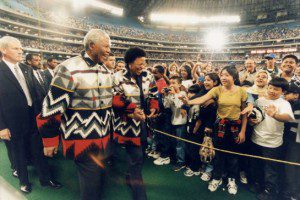

And who but Mandela – in life – could have earned citizenship in a foreign country such as Canada, come to its capital cities amid throngs of well-wishers, attended the inauguration of an elementary school named in his honour, and drawn 40,000 Canadian youth to the SkyDome (Rogers Centre) to hear his electrifying oratory… when the man was in his 80th year of life?

And who but Mandela – in death – could have united so many world leaders (some political mortal enemies such as Barack Obama and Raul Castro) at his memorial this week? Indeed, think of it, on the same airplane to South Africa, as photographed in the newspapers, former Canadian prime ministers Jean Chretien, Kim Campbell and Brian Mulroney sat with current PM Stephen Harper. Most of these people wouldn’t be caught… well, you know.

The day he changed the world, in 1990, Nelson Mandela concluded his Cape Town city hall speech about the democracy he sought this way:

“It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve,” he said. “But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

He died for it. But in peace and in victory.