I think it was my first time at the movies. It was the Birchcliff Theatre on Kingston Road in Toronto. My mom took me. We got popcorn and a soft drink. And the excitement mounted as the movie house lights dimmed, the curtains parted (that’s right, they actually had curtains drawn in front of the screen then) and up came the opening titles as the announcer boomed:

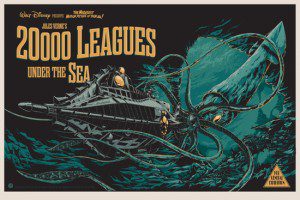

“Walt Disney presents…” and he paused before finishing the sentence, “Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.”

I think all the kids at that matinee screening of the movie, including me, cheered with delight. We were all about to join Captain Nemo, Prof. Aronnax, his assistant Conseil and master harpooner Ned Land in their pursuit of alleged monster in the depths of the sea. Of course, the monster turned out to be a man-made submersible boat, the first submarine, in Walt Disney’s first science fiction movie. It was made in “Technicolor and Cinemascope,” which meant going to the movies was an event.

I think all the kids at that matinee screening of the movie, including me, cheered with delight. We were all about to join Captain Nemo, Prof. Aronnax, his assistant Conseil and master harpooner Ned Land in their pursuit of alleged monster in the depths of the sea. Of course, the monster turned out to be a man-made submersible boat, the first submarine, in Walt Disney’s first science fiction movie. It was made in “Technicolor and Cinemascope,” which meant going to the movies was an event.

Today, I can watch science fiction a hundred times more dazzling than Jules Verne without travelling nearly as far as Kingston Road in Toronto. And I can take it in courtesy of a DVD popped into my computer or downloaded from Netflix. In effect, I can get all the viewing I had at the Birchcliff in 1955 with the insertion of a disc or the tap of a space bar.

What’s even more incredible, perhaps, is that unlike Disney’s requirement for 400 technical crew, the shooting of the giant squid scene in an actual gale off The Bahamas and a budget of $5 million, anybody with computer-generated graphics and a few hundred dollars worth of software can swim circles around the Disney’s classic all on a laptop. And the producer could be you or I. So says Internet columnist Bob Lefsetz, in an editorial published this week, entitled “Where We’re At.”

“Everybody’s a creator,” Lefsetz writes. And he goes on to say that anybody who creates as a professional – with standards, credibility, integrity and attempted distinction – inevitably runs up against the many more hobbyists who enjoy the power of having professional tools (gadgets and electronic wizardry at their fingertips), the disguise of anonymity, and access to global distribution (the Internet) without any track record, reputation or responsibility.

“We’re all concerned with what to watch on our flat screen,” he continues, “but we care not a whit where it’s shown. It’s about the content, not the channel.”

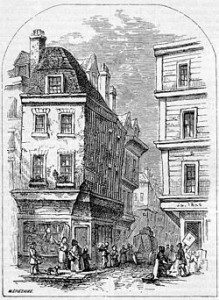

I think it’s the YouTube mentality. If someone can repurpose a piece of content out there more outrageously than anybody else and upload it faster than anybody else, who cares about what it says? A colleague of mine at Centennial College pointed out that the avalanche of non-descript often artless content on the Internet reminded him of a phenomenon called “Grub Street.”

I hadn’t heard of it. With a little research I learned it really was a street in London, England, during the 19th century. A notoriously impoverished area, Grub Street became home to an extraordinary number of hack writers, modest publishers and booksellers surviving not on the quality, but on the quantity of published works. Worse, very little of what the Grub Street hack writers wrote was true.

I remember some of father’s descriptions of Tin Pan Alley in the same light. It’s where music publishers, composers and lyricists gathered on West 28th Street in Manhattan to generate songs, words and recordings purely as a means of generating sheet music sales. Ironically perhaps though, the concentration of such musical talent there as Scott Joplin, W.C. Handy and Louis Armstrong and others generated some of the most enduring forms of American popular music – ragtime, urban blues and jazz – as well as stage shows – minstrel, vaudeville, burlesque and the Broadway musical.

But again, today, a single person (with no particular talent) in a basement studio with just a synthesizer, a mixer and reprocessed (stolen) music tracks can generate any and all of those music forms with the tap of computer key. Lefsetz calls it “an era of chaos.”

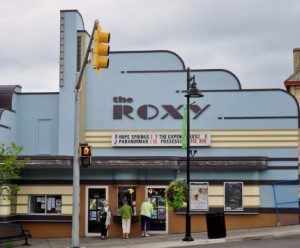

Earlier this week, I attended the annual general meeting of the Uxbridge Historical Society. Local entrepreneur Cathy Christoff was guest speaker, describing her work to build her community-oriented Roxy Theatres (opened in 1996). She explained that from the inauguration of the revitalized location of the Roxy theatre (originally opened in 1955), her modern-day concept of going to the movies is all about entertainment and the senses.

“If it’s just about watching a movie, then the movie business has no future,” Christoff said. “But when it’s an audience taking in the joy, thrills, laughter and tears in a shared experience, then there’s a wonderful future for movies.”

And that’s the difference between watching something gone viral on a computer screen versus going 20,000 leagues under the sea with Captain Nemo at the Birchcliff in technicolor and cinemascope.