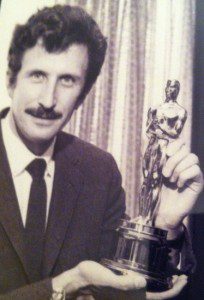

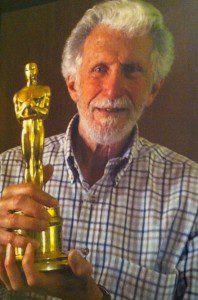

It took us nearly a lifetime to recognize a lifetime. But we finally did it on Sept. 19, 2009. It was a tribute to one of our own – a photographer, innovator and award-winning artist. And in the days afterward, as the person given the distinction of hosting the evening and interviewing the man being honoured, I received two touching written snapshots of the occasion. One came from the subject of the tribute.

“Thank you for your introduction of me,” Christopher Chapman scribbled on a card a few days later. “And thank you for guiding me through that interview.”

The other snapshot came as an email from Christopher’s wife, Glen.

“How thrilling to have a significant number of family, friends and community there,” she wrote. “We’re still in awe of the whole evening.”

The Gala, during that year’s Uxbridge Celebration of the Arts, offered a retrospective on the professional and personal life of a man who, despite his stratospheric stature in the filmmaking profession, chose for much of his adult life to eat, sleep and create in a small community.

Christopher Chapman, after all, had grown up in Toronto, shot motion pictures all over the world, rubbed shoulders with the movie greats, and trail-blazed in the art of film so frequently and so uniquely that Hollywood had recognized his inventiveness and skill with its highest honour, an Academy Award. And yet, as fellow admirer, the Roxy’s Cathy Christoff, recently reminded us:

“Christopher was so blasé about his Oscar, he simply used it as a doorstop.”

Christopher died on Saturday at ReachView with his family around him.

For those not old enough to remember, in 1968, the Academy awarded Christopher Chapman its golden statue for his work on a landmark short film featured at the Ontario pavilion during Montreal’s Expo ’67. Just 17 minutes long, and without a single word spoken by voiceover announcer, but containing all the sights and sounds of industry, entertainment, transport and tranquillity of a province through its four seasons, “A Place to Stand” took Christopher 18 months to shoot and edit. In its creation he invented one of the most inventive optical concepts of the time; he made moving images appear and move on top of moving images without the aid of a computer. The technique he invented manually, now created in seconds with digital animation, was the travelling matte.

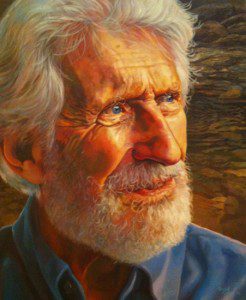

While Christopher gave us perceptive motion-picture masterpieces, all I can offer in personal tribute are mental photo stills of moments shared with this genuine, giving and gentle genius. Of course, I recall the night we celebrated his cinematic achievements and the Oscar. But for me the most memorable moment came during our interview when I asked him what he’d thought of his homage to Ontario.

“It was the most complicated film I ever attempted,” he said. “After the months of production, I thought I had a disaster on my hands.”

“It was the most complicated film I ever attempted,” he said. “After the months of production, I thought I had a disaster on my hands.”

Another snap came from our conversations about a book to which he contributed a chapter. Compiled by Priscilla Galloway and published in 1999 by Stoddard, “Too Young to Fight” offered a story of growing up in wartime that I had learned from others, but never from someone as close as Christopher. Born in 1927 and therefore just 12 when the Second World War broke out, Christopher and his twin brother Francis watched their older brother Bob go off to war in the Royal Canadian Air Force. In the book, the dreaded “regret to inform you” telegram arrived; his navigator brother had died in the crash of a crippled Lancaster in January 1943.

“Withdrawing from the quiet devastation, Francis and I climbed to the attic and our beds,” Christopher said. “As I lay in bed that night, the distant image of Bob smiling before he disappeared into Union Station has never left my memory.” A photographic memory, both natural and trained, no doubt made such an experience painfully indelible.

A final snapshot of a man blessed with talent and modesty to a fault, came to us very recently. During the recent short-film night at the Roxy Theatres, Glen Chapman gave us another reason to love and remember her life’s partner. She loaned us the video excerpt from the 1968 Oscars, when comedian Bob Hope and actress Diahann Carroll struggled with a microphone on a telescopic stand. Just as the two announced “A Place to Stand” as the Oscar winner for Best Live Action Short Subject, the mike stand collapsed into the stage.

A final snapshot of a man blessed with talent and modesty to a fault, came to us very recently. During the recent short-film night at the Roxy Theatres, Glen Chapman gave us another reason to love and remember her life’s partner. She loaned us the video excerpt from the 1968 Oscars, when comedian Bob Hope and actress Diahann Carroll struggled with a microphone on a telescopic stand. Just as the two announced “A Place to Stand” as the Oscar winner for Best Live Action Short Subject, the mike stand collapsed into the stage.

The TV cameras cut to Christopher, dressed to the nines, bounding down the aisle to the stage to receive his prize. Of course, he thanked his family, his peers and the Academy. But what struck me, even with the malfunctioning microphone, Christopher seemed able to broadcast to the world the joy of his moment in the sun. One of many mental snapshot memories of a man who thrived on pictures that moved.

Ted, I have once again read your heartfelt column on Christopher, after his passing October 24, 2015. You are a thoughtful, caring and sensitive writer. Thank you dear one for being such a special friend, to many of us. Love, Glen (Barbara Glen Chapman)