Earlier this week, in the town where I live, there was a little incident on the main street. A car jumped the curb and ended up sideways in front of a few shops. I noticed it because the police were there. I ventured closer and saw a woman, I think the owner of the car, sitting on a storefront step. What intrigued me was that everybody gathering around had the same first reaction.

“Are you OK?” everybody asked the woman.

She appeared shaken, but otherwise all right.

Notice nobody seemed very curious about what had actually happened, what the cause of all this was, or even what the damage appeared to be. As I say, it looked as if the only casualties were flowerbeds and a street bench. But every one of us seemed most eager to know if the woman whose car sat oddly on the sidewalk, was safe. I think our reaction to the incident is indicative of attitudes in a community that keeps close tabs on its citizens, its events, its time and place in the world, and recognizes the importance of saying nice things rather than automatically expressing bad.

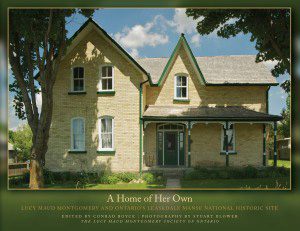

Coincidentally, on the weekend, I attended the launching of two books at the Lucy Maud Montgomery National Historic Site in Leaskdale, Ont. The first book, A Home of Her Own, edited by long-time Uxbridge resident Conrad Boyce with photography by the multi-talented Stuart Blower and published by the LMM Society of Ontario, paints a revealing portrait of Maud. As Boyce wrote, “she lived and died with every ebb and flow of the First World War … realized she never really loved her husband … but put on a brave public smile for the sake of the family.”

Conrad Boyce makes clear that Maud Montgomery lived at least two lives – running a household for two children, presenting competence and stability as the Presbyterian minister’s wife in front of his congregations, and appearing happily involved in the daily life of Uxbridge and area, while revealing darker thoughts in the writings of her voluminous journals. Wrote Boyce, “All of this drama is barely visible between the lines of her fiction.” In other words, Lucy Maud Montgomery offered an upbeat view of the world to her neighbours, but kept her true feelings to herself (and her diaries).

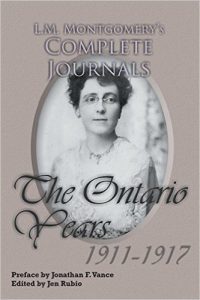

Jen Rubio, the editor of the other LMM book launched on the weekend, The Ontario Years: L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals 1911-1917, carried that point further. For a number of years, Jen Rubio and her mother Mary Rubio, another L.M. Montgomery scholar, have expressed the view that there was more to LMM’s literary genius than just her Anne of Green Gables and Emily of New Moon books. But in earlier editions of the Rubios’ work, they were told (presumably by their publishers) “to take out everything that showed (Maud) wasn’t a happy person.”

In their talk last Saturday, the Rubios illustrated that gossip in Maud’s time was a form of entertainment in rural Canada and that it was therefore safer and more appropriate to be positive in public, while keeping any negative feelings hidden in a private journal. Mary and Jen Rubio went on to say that Maud felt it a duty to say nice things. Indeed, at one point in Anne of Avonlea, her character Anne Shirley asks, “Have you ever noticed that when people say it is their duty to tell you a certain thing, you may prepare for something disagreeable? Why is it that they never seem to think it a duty to tell you the pleasant things they hear about you?”

Maud refers to this quality as “the pointing of duty.”

It’s remarkable to me that too few of those with high public profiles – politicians, entertainers, sports heroes and others – cannot recognize that extraordinary obligation when they make public pronouncements. Donald Trump’s recent outburst concerning the Orlando nightclub massacre comes to mind. My memory of former Mayor Mel Lastman includes his xenophobic outburst, “What the hell would I want to go to a place like Mombasa for? I just see myself in a pot of boiling water with all these natives dancing around me.” Add to that list, some of the public antics of such modern celebrities as Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus, who according to Today’s Parent magazine is “always on the cover of magazines doing bad stuff,” and erring on the side of saying nice things seems an impossibility.

Now I’m not suggesting we all dust off our 1922 editions of Emily Post’s Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home, but I do think some guidance among the handlers, promoters and agents of today’s popular public figures is long overdue. Or as Lucy Maud Montgomery suggests in another Anne quotation:

“It does people good to have to do things they don’t like … in moderation.”