He wore a baseball cap that had no team emblem and a T-shirt with no sign of his number 81 on it. He smiled for several of the private photographs taken that day; and that was a bit out of the ordinary. Otherwise his visit to Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children went unnoticed even when he opened up a case and revealed – for the children and staff at the hospital only – the Stanley Cup, the one he and his fellow Pittsburgh Penguins had won last spring. And his visit would have gone unnoticed, but for a hospital staffer who tweeted:

“SickKids was buzzing with #StanleyCup fever today! Thx for visiting our patients & families @PKessel81 #NHL.”

If the translation escapes you, former Toronto Maple Leaf pro hockey player Phil Kessel traded a year ago to the Penguins, fulfilled a promise and brought the Stanley Cup (during the customary two-day privilege to take the Cup personally wherever each of the winning players choose) to Sick Kids Hospital. But if the tweet hadn’t given it away, Kessel’s visit would have been completely missed by the media.

And that’s exactly the way Kessel intended it. He gave his time and celebrity to a cause that meant the world the kids, but which the world didn’t need to know about.

That’s the kind of celebrity I admire. Not, I hasten to point out, the kind of celebrity we saw during the Toronto International Film Festival nor that which accompanies most fan feeding frenzies around the visits of movie stars, music headliners, sports heroes or royalty. As far as I’m concerned, having a reporter stand on a red carpet just to see who’s arriving and who’s leaving a movie theatre is little better than dead air. Neither is filling media space and time – such as on TMZ – of any redeeming value. It’s following celebrities for celebrity’s sake. Much ado about nothing.

I do, as my first anecdote suggests, admire those who use their celebrity to a valuable end. I can think of such prominent examples as movie stars Audrey Hepburn, Peter Ustinov and Liv Ullman using their fame and reputations to support global assistance for children through UNICEF. And, while they were front-and-centre in such charitable events, Bono and Bryan Adams eagerly supported such causes as Amnesty International, Band Aid and Live Aid, while Neil Young did the same for rural North America with Farm Aid.

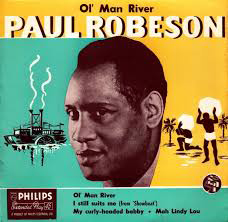

But I think my greatest admiration goes to the likes of Paul Robeson, the African-American athlete, actor, baritone singer and advocate.Born in 1898, in New Jersey, Robeson won a four-year scholarship to Rutgers University, and – despite racism from some of his teammates – won 15 varsity letters and was twice named an All-American in the 1920s. He turned to law for his first profession, but abandoned that career when a white secretary refused to take dictation from a Black man. As a stage performer his leading role in Othello earned him international fame.

In his show-stopping performance of the song “Old Man River” in the musical Showboat, he changed the lines to make a point.

“I’m tired of livin’ and ‘feared of dyin’” became, “I must keep fightin’ until I’m dyin’.”

But Robeson didn’t hide behind the freedom of stage performance. He promoted Black spirituals when they weren’t popular. He sang about justice in more than 20 different languages. He called himself a citizen of the world, befriending other outspoken celebrities of the day, such as anarchist Emma Goldman, and authors James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway.

In 1933, a published biography pointed out that Robeson donated proceeds of his release “All God’s Chillun” to Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany. And in 1937 he openly supported the Republican government against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

“The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery,” Robeson said. “I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

For his support of Blacks and labour in America, the House Un-American Activities Committee labelled him a Communist. The accusations ended his singing career because no one would hire him and his passport was revoked. He died nearly broke and broken in 1976 at age 77.

“As an artist I come to sing, but as a citizen, I will always speak for peace, and no one can silence me in this,” he said.

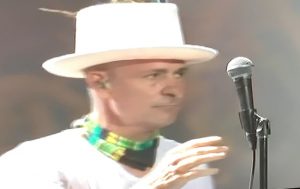

This week, half a century after Robeson, another singer from another era used his celebrity to make an equally powerful statement. Tragically Hip’s frontman Gord Downie announced Sept. 20 that he’ll perform two concerts in Ottawa and Toronto in support of the Secret Path project. His shows will honour Chanie Wenjack, an Ojibway boy who died of hunger and exposure attempting to flee a residential school 50 years ago.

“Chanie haunts me,” Downie told CBC News. “His story is Canada’s story.”

And given that Downie has told us he has terminal brain cancer, these shows are clearly not about Gord. They’re about a gift, a cause and celebrity worth applauding.