We had finished our preparations. I’d checked the microphone levels with the sound technician at the venue. We had loaded all the visuals supporting my talk into the theatre’s projection system. The script? I knew all the stories by heart. Everything seemed ready for my presentation about the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Suddenly, everything changed. A woman entered the theatre and then came out of the box office shaking her head. I spotted her and asked what was wrong.

We had finished our preparations. I’d checked the microphone levels with the sound technician at the venue. We had loaded all the visuals supporting my talk into the theatre’s projection system. The script? I knew all the stories by heart. Everything seemed ready for my presentation about the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Suddenly, everything changed. A woman entered the theatre and then came out of the box office shaking her head. I spotted her and asked what was wrong.

“Oh, it’s nothing,” she said. “I just wanted to talk to tonight’s speaker, but there are no tickets left, so I guess I’m out of luck.”

“I’m the speaker,” I said. “What was it you wanted to say?”

“It’s a story about the sculpture on Vimy Ridge,” she said.

I thought I knew most of the story about how Canadian sculptor Walter Allward had come to carve that magnificent limestone memorial atop Vimy Ridge. I knew that in 1923 the government of France had offered Canada 250 acres near the military position known as Hill 145 for the erection of a monument commemorating the exploits of the Canadian Corps in the Great War.

I’d heard that “on an envelope out of his pocket and in a few bold pencil strokes (Allward had) indicated the general idea of two towering pylons of stone.” I knew that Allward, had begun working in earnest on his design at age 44, that he had assembled 150 different drawings, and that his design, when chosen by the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission, would take a dozen years to create.

“I saw a great battlefield,” Allward claimed, recalling a vision he’d had in a dream. “I saw thousands marching to the aid of our armies. They were the dead. They rose in masses and filed silently by and entered the fight to save the living. … I have tried to show in this monument to Canada’s fallen, what we owed them.”

I had learned that Allward’s sculpture required 11,000 tonnes of concrete, reinforced by hundreds of tonnes of steel. The memorial itself – about 200 feet square at the base and about 125 feet high – consisted of 6,000 tonnes of limestone from an abandoned Roman quarry on the Dalmatian coast.

I knew that Allward’s two pylons would depict the principles of Faith, Charity, Honour, Peace, Justice, Truth, Knowledge and Sacrifice in human figures, and that atop the wall of defence with its 11,285 inscribed names of the dead, would be “Canada Bereft” (a.k.a. Mother Canada) mourning her dead.

“We have to contemplate a structure which will endure in an exposed position, for a thousand years,” Allward said, “Indeed, for all time.”

All that I had learned from years of reading and recording. But in all my research, I had never heard what this woman I’d just met in the lobby of that theatre in Sherwood Park, Alberta, told me a few weeks ago.

That’s when Rosemarie Biggs offered me a piece of history about Vimy I didn’t know. She began by describing the life of Edna Jennings, a young artist, whose only ambition was to become a professional dancer in the early days of the 20th century. When she got her chance, in the 1920s, she toured with a dance troupe around Britain.

Suddenly, Rosemarie Biggs lamented, Edna fell ill with typhoid fever. Doctors told her to retreat to her bed to convalesce, or die. As she waited at home for her strength to return, a dancing pal named Joy visited her and told her about an advertisement in a theatre magazine. An artist visiting England needed female models for a piece of art he was designing. Joy had actually gone to a modelling audition, but was told her body shape didn’t suit the artwork, that “her shoulders weren’t broad enough.” Biggs said that Edna Jennings visited the artist and while modelling even had her shoulders measured with callipers.

“It turned out Edna’s shoulders were just what the artist was looking for,” Biggs told me. “The artist was Walter Allward and his planned figure was to be part of his monument on top of Vimy Ridge.”

“You mean Edna was the model for Mother Canada?” I confirmed.

“And I am Edna’s niece,” Rosemarie Biggs said proudly.

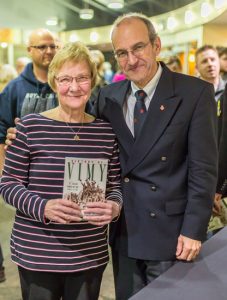

Later that night, as I completed my Vimy presentation on the theatre stage and received generous applause from that Alberta audience, I bowed in thanks and said that the Vimy story continues to deliver even in 2017. I related the story that Rosemarie Biggs had given me that very afternoon. And thanks to a gracious gift from some bandsmen, Rosemarie had received a ticket to our show.

The lights of the theatre came up as I introduced her in the balcony:

“Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Rosemarie Biggs, the niece of Edna Jennings, whose broad shoulders are captured forever in the sculpture of Mother Canada on Vimy Ridge.”

Dear Ted Barris

Thank you very much for this.

I am Edna Jennings daughter and close cousin of Rosemarie.

I am delighted that my mother is being honoured in this way.

She was sad that she had never seen the Memorial herself, as the main work was done in London, and then cast in France. I took her to see it in the ’70s and she was quite overwhelmed as you can imagine.

You need to see it ‘live’ to get the full impact and magnificence.

Thank you again

Sue Jennings

What a beautifully written article.

My partner, John Jennings is Edna Jennings’ son.

He and his four siblings are all very proud of their mother’s part in the breathtaking Mother Canada statue. He last gazed in awe at his mother’s statue nearly sixty years ago. John says, the statue is very like his mother as he remembers her as a young woman.

John is the family historian and, at eighty-six years old, plans to travel from Malvern in Worcestershire, UK, to Vimy for VE day next year (2018) to celebrate the poignant centennial of WW1.

John is currently trying to discover what dates would be the best to attend, perhaps someone reading this might have any helpful tips?

I am Andy, grandson of Edna. We have just visited the statue for the 6th time, today with Edna’s youngest grandson Anthony who is just 1-year old. We live in southwest England U.K. Thank you for the article.