On my last day of classes in 1964, with nothing left to teach us, my Grade 9 phys-ed instructor just gave us a bat and a ball and told us to go play some baseball work-ups. I loved playing shortstop, the position my dad liked most too. Not long into the game, however, the catcher and I chased the same infield fly and we collided head-on. I broke my nose, lost some front teeth and was knocked out cold. I spent several weeks recuperating at home in bed. My father happened to be writing in his office at the house, so he spent time trying to distract me from my pain by telling me stories. It wasn’t long before I popped the big one.

“Hey Dad, what did you do in the war?” I asked.

I didn’t realize it then (I was 15), but my father – Alex Barris – employed the same safety mechanism many veterans of the Second World War, the Korean War and Afghanistan have used. Never tell the rough stories, the remembrances of destruction close by. Don’t revisit the moments of death and dying. Under no circumstances let loved ones see you break down and cry. Instead, protect them from the truth. Always recall the antics, the quirky tales and maybe the odd near miss. But never let them know the hell of your war.

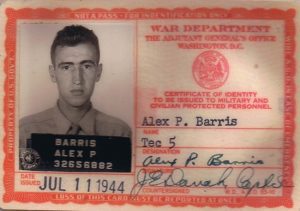

That’s what my father did. For several afternoons in a row, as I lay in bed recovering from my schoolyard wounds, my father regaled me with just the war stories he knew would leave me laughing. During the Second World War, my father, born and raised in New York, was trained as a medical corpsman. For a year, he endured U.S. Army training camps from Kansas to Mississippi. He rose to the rank of sergeant.

During one training stint in the winter of 1943, at Camp Phillips, Kansas, he was assigned the job of waking the battalion commander before dawn so that the officer would be the first on the parade ground to conduct first roll call. One morning, fearing he might sleep through his alarm, my father accidentally woke the commander an hour early. Dad used to wince at the recollection of his senior officer shouting into the freezing Kansas pre-dawn:

“Company A, report! … Company B, report!”

Nobody answered because nobody was up yet.

My father told me about army food – C rations, or “shit on a shingle,” and coffee that tasted like mud. Everybody in the army hated the food and the cooks hated everybody back, he told me. Nobody ever got any food he liked. So, from the moment he received his baloney sandwich ration each morning until noon when he had to eat lunch, my father searched for anybody who hated the peanut butter sandwich ration as much as Dad hated his baloney sandwich ration. Only then could he eat lunch – two peanut butter sandwiches.

And on the stories went. Anyway, towards the end of those days of my convalescence at home that June of 1964, I asked my father one last question about his war. “Did you get any medals?” Presently, my father retrieved a medal hanging from a short maroon-and-blue, striped ribbon. He made no fuss over it. He shrugged off any mention I made of his wartime bravery. He simply suggested, if I really cared about it, that I should put it in safekeeping.

So, while I had managed to get an answer to, “What did you do in the war?” it was the answer he’d chosen to give me. He had gone only as far as he felt comfortable. The rest would have to be left to my imagination, or if I cared enough, to find out on my own someday.

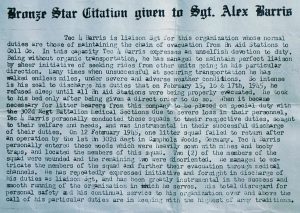

In the last year of my father’s life (2003-2004) – after he’d suffered a debilitating stroke that took away his memory and his speech – I came across a military citation in his personal papers. It described a night in February 1945, in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge, the bloodiest American engagement of the war, when my father personally retrieved four of the medics in his platoon from a booby-trapped, land-mined and snowbound area in Germany, known as Campholz Woods.

In the last year of my father’s life (2003-2004) – after he’d suffered a debilitating stroke that took away his memory and his speech – I came across a military citation in his personal papers. It described a night in February 1945, in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge, the bloodiest American engagement of the war, when my father personally retrieved four of the medics in his platoon from a booby-trapped, land-mined and snowbound area in Germany, known as Campholz Woods.

“His total disregard for personal safety,” the citation for the Bronze Star stated, “are in keeping with the highest of army traditions.”

Well, for those of you who’ve heard me tell this story repeatedly before, this week, I hope I will add a small chapter to my father’s life. For a number of years, I have tried to find the time and means to track down my father’s experience at Campholz Woods, during that horrible last winter of the war. This week, I shall come as close as any member of my family has to learning the truth about my father’s service in uniform under fire. I will walk the ground my father did 72 years ago. And I hope I’ll learn a bit of the truth of my father’s war. Stay tuned…