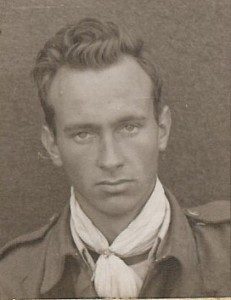

As distant as the 2,000 air officers inside the North Compound at Stalag Luft III felt from their original wartime British air stations thousands of kilometres to the west, on the eve of their historic breakout, the POWs were remarkably close to the U.K. by air waves… thanks to Canadian Richard Bartlett.

Born and raised on a dairy farm near Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, in western Canada, Bartlett raised silver foxes, the assets of which provided him with passage to England and entry to the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm by 1938. Posted to 803 Squadron and flying Skua dive-bombers in the spring of 1940, S/L Bartlett flew in the futile defence of Norway against the Nazi invasion. That June he was shot down and was shipped off to POW camps in northern Germany and Poland. He got involved in clandestine work right away.

“Through friendly relations with Polish labourers at (Stalag Luft I), we bribed one of the Poles to sneak the components for a small radio receiver into the camp.”

And the resulting wireless set allowed the POWs to hear BBC broadcasts. Then, to ensure that the crystal set was never discovered by German guards, Bartlett regularly disassembled the crystal set and placed its parts inside a medicine ball. The ball, a bit larger than a basketball and usually weighted with sand, was used by prisoners of war for calisthenics and other sporting pursuits.

“That way, the radio-equipped medicine ball subsequently travelled from camp to camp (becoming) a continuous source of war news and intelligence,” Bartlett pointed out. In this fashion, by the time the Commonwealth aircrew men had arrived at Stalag Luft III and throughout their stay there, kriegie Richard Bartlett served the escape committee as the custodian of the canary.