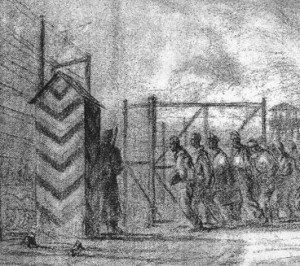

If the 1963 movie portrayal of The Great Escape succeeds in delivering the drama and tension leading up to the mass breakout planned for late March in 1944, it utterly fails to capture the reality of winter in western Poland.

On March 1, as F/O John Colwell recorded in his diary, six inches of snow fell. Temperatures generally dipped below freezing pre-Christmas and stayed there until April. Even kriegies used to cold winters in Canada, found conditions at the North Compound of Stalag Luft III tough to endure.

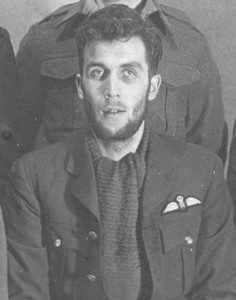

Flying Officer Don McKim’s Halifax bomber was shot down over Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, in December 1942, in a frigid 185-mile-per-hour wind. Still, on Christmas Eve, having to sleep in the bottom tier of a bunk bed – closest to the floor – McKim said he was never so cold in all his life.

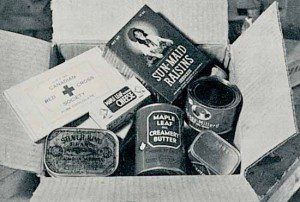

“The mattress was made of bags of wood chips,” he said, “so, the cold would work its way through (and) I put all the clothes I had on. My greatcoat. My mittens. Everything trying to stay warm.” McKim was claustrophobic, so he worked as a stooge, yes, outside in the winter air passing X Organization communiqués.

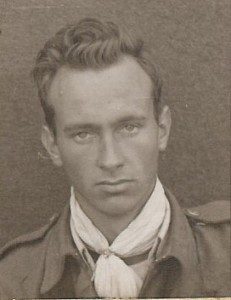

Equally affected by freezing temperatures, Pilot Officer Frank Sorensen (shot down over North Africa in 1943) wrote of the environment and its impact on him often during his first winter at Stalag Luft III. On Feb. 25, 1944, he wrote to his father, “It’s been very cold here lately (and) as I am very restless, unable to keep my blankets on me at night, I sewed them into a sleeping bag.”

And a few weeks later, he wrote about winter dragging on, “leaving the ground wet and miserable and forcing most everyone to remain indoors. Indoor life in a kriegie camp does not make time go any faster.”

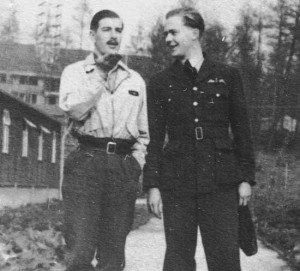

Sorensen contributed in many ways to the escape effort, but among the most valuable required him to be outside. Big X (Roger Bushell) was fluent in German, French, and some Russian phrases, but he was deficient in Danish. Since Sorensen had been born in Denmark, through the fall and winter of 1943-44, the two walked along the circuit (just inside the warning wire where they couldn’t be heard by guards or any other listening devices) as P/O Sorensen taught Big X common Danish phrases that Bushell could use if he escaped and got aboard a vessel sailing from Germany toward Scandinavia.