The Queen, the French prime minister, Prime Minister Harper, assorted other dignitaries, at least 4,000 young Canadian students and thousands of French and Canadian citizens were there. They had all assembled on a hillside in north-central France to commemorate perhaps Canada’s greatest military victory in the Great War at Vimy Ridge, on April 9, 1917. The tour of 112 people, for whom I’ve provided commentary this week, had dispersed into the overall crowd of 25,000. Suddenly, this older man approached me.

“You are a Canadian?” he asked.

“Oui,” I said, in my awkward attempt to speak his language.

“Here. Take this,” he said and he gave me a CD of images containing inscriptions from surrounding villages and towns commemorating Canadians who had helped liberate France 90 years ago. “It is small thanks for what your countrymen did.” And as I fumbled for something to give him in return he said, “I expect nothing, please, nothing in return.”

It was one moment in an altogether extraordinary day.

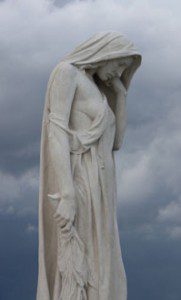

We had arrived at the summit of the ridge about 10 a.m. Our bus wove its way through the hundreds of other vehicles lining up to disgorge their passengers. We had then gathered at Walter Allward’s famous memorial itself – twin pylons towering 125 feet in the air – honouring more than 11,000 of Canada’s Great War dead who had no known graved. There, our group enjoyed a private interview with Julian Smith, the architect in charge of refurbishing the monument. When I asked him how felt he said that news of the latest six Canadian troop deaths in Afghanistan had just arrived. It made the moment of the rededication of the Vimy Memorial (originally unveiled in July 1936) all the more sobering and important, he said.

Then, as the RCMP, the French security police, the host broadcasters, the grounds crews and the Vimy Ridge interpretive staff all prepared for the main event, at 4 o’clock, I wandered the historic site to get a feel for the day. Near the site cemeteries, I encountered a piece of home.

Three Port Perry High School students, who were part of the “Return to Vimy” youth tour, approached me and shared their stories. Not own stories, but the stories of three Canadian soldiers who served at Vimy. (There were 3,598 killed and another 7,000 wounded.) Robb Phillips told me of Cpl. Joseph Kennedy, his great grandfather wounded by machine-gun fire. Cotter Allen carried with him the story of Cpl. Arthur Barnard, who died at Vimy at age 35. And Michael Riseley told me about his chosen Vimy soldier, Pte. Ralph E. Bowen, a peacetime plumber who died at Vimy on the first day of the battle – 90 years ago this very day.

Then, I met the MacDonald family from Uxbridge. Father Mike was performing as part of the Vimy ceremonies with the Highland Creek Pipes and Drums. Tish MacDonald was there chaperoning a group of the Return to Vimy youngsters. And their daughter Rebecca MacDonald was there wearing the name of her grandfather, who fought with the Canadian Corps and lost an arm in combat just before the war ended in November 1918.

“I can’t believe there’s a ton of Canadians over here,” Rebecca told CBC broadcaster Rex Murphy on the air Sunday night.

She was right. Also in the crowd from Uxbridge were Bill and Elinor Cole; Bill’s father Thomas Clark Cole (with the 48th Highlanders) was wounded on the first day of the battle by machine-gun fire and walked several kilometres to get first aid; and Elinor’s uncle John Raymond Gaetz (from Red Deer) had also served during the victory on the ridge. Meanwhile, long-time Uxbridge resident Barb Pratt had coaxed her two brothers – Wilf and Jim Hewlett – to come to Vimy as a pilgrimage in tribute to their Vimy vet father, Bill Hewlett. When I asked Barb of her impressions, she said one brother had told her “I’m glad you coaxed me to come.”

Back in the crowd waiting for the rededication ceremony to begin, another man approached me. Laurence O’Neill told me he once served in the military and as his retirement ritual he regularly comes to Vimy. This was his tenth trip. He said he was just another ordinary Canadian paying his respects. And that’s what made these modern pilgrims, not to mention the original Canadian volunteer troops at Vimy, so special.

Ordinary people had gone to such extraordinary lengths to make it happen.