It was back about 1973 that a movie caught my attention.

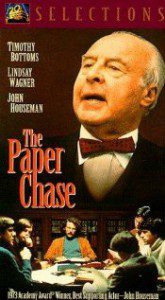

The Paper Chase, based on the novel by John Jay Osborn, depicted a group of first-year Harvard Law School students. Like so many university freshmen, the movie frosh ran scared from nearly every class. Then they banded together into a study group, pooling their notes on civil law discussions, criminal law tutorials and, in particular, the contract law lectures of the dreaded Prof. Charles Kingsfield (played by John Houseman). Lead character James Hart (played by Timothy Bottoms) described the study group as an act of self-preservation.

“We band together,” he said, “or we fail!”

Notice he did not say, “Share essays and answers to tests.”

The object of The Paper Chase study group was to take full advantage of every student’s strength and overcome every student’s weakness, by sharing accumulated knowledge and healthy study habits. As often as it could, the study group met and compared notes, each session led by the student who excelled in that particular course. Again, notice that the idea was to prepare for assignments and testing, not to exchange the answers. Not to cheat.

On Tuesday of this week, a Ryerson computer engineering student faced a hearing on charges of academic misconduct over his alleged activity with an electronic study group, linked via Facebook. The university contends that first-year student Chris Avenir joined an online group originally to get help with his homework, but that he eventually became administrator for 147 classmates all swapping assignments worth as much as 10 per cent of semester marks. Ryerson has the option of expelling Avenir.

The case has sparked a firestorm of response:

James Norrie, of Ryerson’s School of Information Technology Management, said, “Sharing of answers defeats the purpose of learning.”

A doctoral student in North Carolina, Fred Stutzman, said, “Cheating is cheating and collaboration is collaboration. Because there’s a virtual environment doesn’t change the definition.”

But CBC Radio’s technology commentator Jesse Hirsh called Ryerson’s reaction “ludicrous” and “heavy handed.”

And Market News editorialist Chrstine Persaud wrote: “Who cares? How is this any different than a group of students getting together in a local coffee shop or at someone’s house to do their homework together?”

The difference, I think, is that the Facebook study group appeared to make data available to its Ryerson members that went beyond completing homework. Apparently, right on its title page, Avenir’s site encouraged members, “if you request to join, please use the forms to discuss/post solutions to the chemistry assignments.” That appears to me to be more serious than comparing notes at a kaffeeklatsch.

And, who cares? I care because I work in a teaching environment. At Centennial College (and I think at other communications schools) we define fabrication (invention of stories) and plagiarizing (taking someone else’s) in a clear, sombre fashion. We make even more clear the consequences of such conduct – zero grades and, if repeated, expulsion. We try to teach young journalists that the profession expects ethical behaviour and that graduates will deliver nothing less. In fact, to ensure that code of honour is understood and respected, as of this current semester, we invite every journalism undergraduate to make an academic honesty pledge.

“I know that our readers and audience demand accuracy and honesty about where the information they are consuming comes from,” the contract reads. “And because the industry insists on rigorous standards … I pledge to act professionally at journalism school and for news organizations where I may be employed.” And then, as a commitment to the school, the profession and his/her peers, each student signs the pledge.

Not for a moment do I suggest that a contract eliminates the problem. As recently as last month, another Toronto journalism school student announced she had used a pseudonym, fabricated more than a dozen stories during her two semesters in the program and maintained an ‘A’ average before bailing out of the course to answer a greater calling – writing fiction. Unfortunately, such cheating forces teachers to search for new ways to catch it. We read, check and double check story sources. We scour the Internet hoping we won’t find abuse, but knowing full well it’s out there.

Meanwhile, we encourage the kind of practice depicted in The Paper Chase, where students legitimately inspire each other and build on each other’s strengths. It’s evident, however, that we’ll continue to find the realities of Facebook cheating, just as likely as the fiction of a John Jay Osborn study group.