Ninety-one years ago this week, the men of Zephyr, Sandford, Sunderland and Uxbridge came away from Passchendaele, Belgium.

In three and a half months of fighting that fall of 1917, Canadian troops – including members of the 116th Battalion from Ontario County – had managed to seize about six kilometres of ground from the occupying German army. Before the battle, the Canadian Corps commander, General Arthur Currie, had forecast to his British superiors that taking Passchendaele would cost 16,000 Canadian casualties. He was almost exactly correct; 15,654 Canadians died, were wounded or captured there.

“Passchendaele!” Currie had exclaimed before the battle. “What’s the good of it? Let the Germans have it – keep it – rot in the mud.”

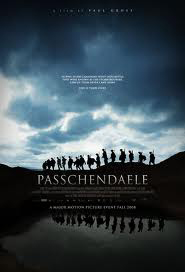

“Passchendaele,” opened this week for movie-goers – three generations later – to learn what some of the men of Ontario County experienced in the Great War.

Among those who survived that bloody encounter 91 years ago, was a 19-year-old farm boy from Reach Township. Lyman Nicholls had played hooky one afternoon from Uxbridge Secondary School to join up.

He’d received his uniform, boots and enlistment papers, but by nightfall his parents had un-enlisted him because he was underage. By that summer when he turned 18, however, Nicholls legally joined up and went to war. He survived a baptism of fire at Vimy Ridge and then Passchendaele.

“Some of us signallers acted as a stretcher party,” Nicholls later said.

An officer gave him a white flag to presumably protect him from enemy machine-gun fire as members of the 116th picked up Canadian wounded. Nicholls remembered walking along wooden duck boards to keep him from sinking in the muddy bog. He and his fellow stretcher bearers walked in single file toward two German pillboxes where the wounded men awaited their assistance. Among the wounded Nicholls brought back was a young German prisoner.

“I was last (man) behind those stretcher cases and I held the German prisoner by one arm and held up the white flag, as high as I could, expecting at any minute we might be killed…But we got back safely,” Nicholls said

As military decision-makers often do, British Field Marshal Douglas Haig sensed the battle for Passchendaele would become the greatest victory of the 1914-1918 war. Haig himself described the place as little more than “valleys with overflowing streams…speedily transformed into long stretches of bog, impassable except by a few well-defined tracks.” Still, the final push to capture this strip of land from the German army in central Belgium, fell to the Canadians.

Another Uxbridge man who served at Passchendaele in 1917 was the commander of the 116th Battalion. It was Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Sharpe who had proposed, recruited, underwritten and trained the 1,100 volunteers from Ontario County to go to war. He and his adjutant had written of their citizen army that each man had nothing but “an ardent desire to get through the baptism of fire with as much glory and as few casualties as possible.”

But by the time the 116th got to Passchendaele, about a year later, the night raids across No Man’s Land, the frontal attacks behind creeping barrages, the repeated counterattacks of German gas, artillery and infantry, had worn the battalion down. Not in spirit, but in cumulative losses. The first seven months of service on the Western Front had killed or put out of action nearly a third of the battalion’s strength. Then, anticipating Passchendaele, Lt. Col. Sharpe wrote a letter home to Uxbridge.

“We have very little protection there and I may not pull through,” he wrote his wife, Mabel. The letter came across as a kind of last will and testament. “If it should be my fate to be among those who fall, I wish to say I have no regrets to offer. I have done my duty … I die without any fears as to the ultimate destiny of all that is immortal within me.”

Passchendaele all but destroyed the 116th. Of the 1,100 men who had volunteered in 1915-16, only 160 would come home. Lyman Nicholls, the signaller from Reach Township, survived his stretcher bearer duties there, but was wounded soon after at Cambrai. Lt. Col. Sharpe was less fortunate. A man broken by the fatigue of battle and the decimation of his battalion, never got home to Uxbridge; he committed suicide at a Montreal hospital in the spring of 1918.

Passchendaele, the battle, symbolized the war’s futility. The movie that arrives here tomorrow will remind this community – and any others that supplied citizen soldiers to the Great War – of the human cost.