What is it about February and Canada?

It’s certainly a month that defines this country. Whether it’s the frigid temperatures and snow we’ve endured or the national symbol we sort of celebrate (it was on Feb. 15, 1965, that officials raised the Maple Leaf flag on Parliament Hill for the very first time), this month makes most people between Bonavista and Vancouver Island express their distinctiveness. But in February we have another aspect of Canadiana to celebrate. It was 30 years ago this month that Canadians acknowledged Black History Month for the first time.

What makes Black History Month distinctively Canadian? Well, to my knowledge, it’s not celebrated anywhere else in the world. What’s more, I met an African-Canadian man, this week, who stopped me in my tracks.

“My family is older than Canada,” he told me.

David Watkins is absolutely right. Born in Windsor, Ont., in 1964, Watkins is a seventh generation Canadian. His father’s ancestors escaped slavery in Virginia in the late 1700s. His mother, from Arkansas, emigrated to the Detroit area in the 1940s; she became one of the first black nurses in the region, while Watkins’ father became Canada’s second black police officer. One of his relatives – a runaway black slave from Milwaukee – used the Underground Railroad (hiding beneath a false floor in a buckboard) to escape her American slave masters.

“We were the first United Empire Loyalists,” Watkins said. “The idea of being Canadian is who I am.”

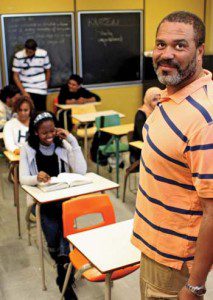

What makes David Watkins even more Canadian than that, is that he teaches history in a downtown Toronto high school, in fact, in one of those so-called “at risk” neighbourhoods. He doesn’t teach the kind of Canadian history you and I might remember – the BNA Act, the War of 1812, the rebellion of 1837, the great Depression or even the Avro Arrow, the Summit Series and the invention of the Blackberry. No. Watkins teaches African-Canadian Studies to Grade 11 classes at Weston Collegiate Institute. He teaches mostly black students how African history relates to Canada, how the young people in his classrooms should connect to the past, present and future of their country.

“Why study black culture as a key Canadian history?” he asks rhetorically. “You can’t go from point A to point B unless you know what your point A is.”

Watkins has been a proponent of the planned African-centric schools in Toronto. He teaches his students that studying history is the key to self-determination and self-awareness. Once they see their own experiences – not those of black Americans – reflected in their nation’s history, then African-Canadian students, he says, can begin to have a vested interest in their surroundings. They break the U.S. stereotypes (depicted in some degrading hip-hop lyrics and so-called “gangsta” accessories) and realize their home is unique. In other words, they find their point A and are comfortable with it.

Educator Watkins also acknowledges the tougher side of his existence – including racial profiling. On one occasion, he said, he returned to his home in middle-class Toronto, stopped in front of his house, jumped out of his car and ran across the lawn to the front door of his house. Within seconds, he said, there was police car with emergency light flashing checking out his identity. And he says, on several occasions he’s been stopped for no other reason than the colour of his skin. He called it “DWB…Driving while black.” Incidents such as that motivate him all the more.

He teaches his history students to ask themselves three questions about their history: What was? What happened to change it? And, what was the result? Answering those questions inevitably takes them back to their roots in Africa or the Caribbean. Not to America, where, he says, young blacks tend to “emulate desperation.” But Watkins doesn’t shy away from those negative images he senses his students are attracted to. He fights the negative stereotypes of black culture as much as anybody, including the dark side of hip-hop culture.

“If you’re one of these cats that’s just talking smack, saying ‘I do this’ and ‘I do that,’ for the sake of a buck,” he told one news reporter, “you’re part of the problem.”

By the way, David Watkins’ technique is working. Today, the Toronto District School Board has him teaching other teachers, so that they can inspire that many more African-Canadian students at Ontario schools. And this past year he caught the attention of the Governor General. Michaelle Jean presented him with the Award of Excellence in Teaching.

And that’s a piece of Canadian history worth celebrating any month of the year.