The tour guide had nearly finished his talk.

The tour guide had nearly finished his talk.

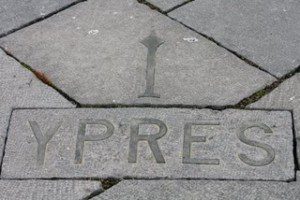

He had led a group of Canadian tourists (I was hosting) through a former European wasteland. Just over 90 years ago, the centre of Ypres, Belgium, was little more than rubble and mud. Fighting between invading German armies and Allied forces (including thousands of Canadian troops) defending the Flemish city had levelled everything recognizable. The First World War had left virtually every building in the city core in heaps of broken stone and splintered wood. Then tour guide Raoul Saeson pointed to a disintegrating wall of the former rectory near the reconstructed St. Martin’s Church.

“It’s the only part of Ypres that has been left as it was in 1918,” he said. “Every other part of the city has been restored to the way it was.”

My recent trip through the former battlefields of France and Belgium has opened my eyes to the remarkable recovery that people here have achieved in the wake of the two World Wars of the 20th century.

Earlier during that same day, tour guide Saeson had led us through the city’s former Cloth Hall. There, beginning in the 13th century, makers of the finest linens in Europe had gathered year-round to buy and sell their wares. On Nov. 22, 1914, three months into the Great War, the first shells from attacking German artillery crashed into the hall, eventually reducing the structure – about the size of three St. Lawrence Markets – to rubble.

Not until 1967 – more than a half-century later – was the rebuilding process of the structure finally completed. Today, the Cloth Hall (looking like the original marketplace on the outside) has been transformed into the In Flanders Fields Museum.

Each day the facility welcomes thousands of visitors to learn what daily life in Ypres was like during the 1914-1918 war. It houses the most vivid and personal displays of the wartime experience I’ve ever seen.

About 40 kilometres south of the city of Ypres, near the French town of Armentieres (yes, as in the song “Mademoiselle from Armentieres”), a restoration of a different type has recently begun. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, since 1917 the organization that has respectfully buried member nations’ war dead, erected tombstones and tended cemetery gardens, recently began a new project. At Fromelles, where in 1916 the Australian army suffered “the worst 24 hours in its history,” CWGC archaeologists are unearthing a mass grave and attempting to identify (via DNA) and then bury individually the 400 soldiers interred there.

A sign raised near the newly surveyed Australian cemetery in the town of Fromelles captures the essence of this reburying initiative:

“Don’t leave me behind, cobber,” Aussie troops would often call to their comrades in distress.

The individual, recorded and marked reburials, reuniting many of those 400 Australian troops with their lost identities will begin later this year.

The same day on this recent tour, my tour group travelled to Passchendaele, east of Ypres, where from July to November 1917, members of the Canadian Corps and other Commonwealth regiments had attempted to smash through the German front lines (as they had done successfully at Vimy in April 1917). For one member of my contemporary tour – Yvette Rumple, from Kelowna, B.C. – the Passchendaele area known as Polygon Wood held particular significance.

During the offensive on Oct. 8, 1917, Yvette’s father, Frederick Owen, was hit in the leg by shrapnel in a shell hole. There he lay bleeding for 24 hours, nearly dying before two sympathetic German soldiers (using a flag of truce) pulled him out and delivered him to a British first-aid station.

“My father lived,” she said. “The rest in that hole died.”

That afternoon this past week near Polygon Wood, Yvette and I stepped off the tour bus into what is now an early spring planting of corn. As she took pictures of the area where her father fought and survived his last battle, I walked out into the rows of corn, filled a plastic vial with damp earth from the field and presented it to her.

For Yvette Rumple, Frederick Owen’s now senior-citizen daughter, the moment had closed the circle, connected her with her father’s remarkable wartime story, and restored a piece of that wartime battlefield to one of its victors.

For Yvette Rumple, Frederick Owen’s now senior-citizen daughter, the moment had closed the circle, connected her with her father’s remarkable wartime story, and restored a piece of that wartime battlefield to one of its victors.

Meanwhile, just outside that same In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, a ceiling-to-floor piece of art, called “Martyred Cities,” reminded visitors such as us North Americans, that while they are restored on the outside, places such as Ypres, Coventry, Rotterdam, Dresden, Hiroshima, My Lai, Jerusalem and Srebrenica, still bear the unhealed scars of war inside.