The world ended that night. A high school girl in a major eastern city was hysterical; she claimed she and her girlfriends cried and held each other preparing to die. Rural residents on mid-western farms prayed harder than they ever had before. And thousands more rushed headlong into the streets of New York City that night. They hallucinated that aliens from outer space were invading their city, their country, their planet. They’d heard a radio broadcast – 71 years ago tomorrow night – and thought it was really the end of life on Earth.

The world ended that night. A high school girl in a major eastern city was hysterical; she claimed she and her girlfriends cried and held each other preparing to die. Rural residents on mid-western farms prayed harder than they ever had before. And thousands more rushed headlong into the streets of New York City that night. They hallucinated that aliens from outer space were invading their city, their country, their planet. They’d heard a radio broadcast – 71 years ago tomorrow night – and thought it was really the end of life on Earth.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” they heard the announcer say, “this is the most terrifying thing I have ever witnessed! … Wait a minute! Someone’s crawling out of the hollow top … Someone or something. I can see peering out of that black hole two luminous discs … are they eyes? It might be a face…”

Fright, real fright was born Oct. 30, 1938.

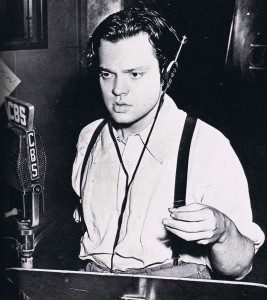

It was that pre-Halloween night that a bunch of daring writers, actors, producers and sound effects technicians successfully fooled many North Americans into believing that an invasion of hostile Martians had begun. Known as the “Mercury Theatre of the Air,” the radio troupe had rehearsed all week in the CBS Radio studios in Manhattan. Their writer – Howard Koch – had adapted an H.G. Wells science fiction story (set in 19th century England) and updated it to the uncertainty of the late 1930s in the U.S. Their director and leading actor – Orson Welles – had then led the cast into the original live broadcast of “The War of the Worlds.”

It was totally convincing. Within minutes of the start of the broadcast, regular listeners to CBS heard on-location music from the ballroom of an identifiable New York hotel. But then the first of a series of interruptions began – each one more threatening than the last, each offering bulletins about odd explosions noticed on Mars, and each voices of authority warning of a major, national threat from the heavens. What proved even more extraordinary than the broadcast itself, however, was the degree to which the North American public believed what it was hearing was actually happening.

Why did it work? Well, there were only two radio network shows on the air that night – “Mercury Theatre” on CBS and the “Chase and Sanborn Hour” (with ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his smart-mouthed dummy Charlie McCarthy) on the rival NBC network. In fact, some who started listening to Bergen and McCarthy and switched over to CBS did not hear the disclaimer identifying the show content as a dramatization of H.G. Wells’ sci-fi story. The format of the show – a series of news bulletins interrupting regular programming – proved entirely believable. Actual places – in New Jersey and New York – were named. People in authority – reporters, scientists, police and military spokesmen – were interviewed with credible sound effects and appropriate stumbles to give the on-location atmosphere plenty of authenticity. Ultimately though, radio was trustworthy. People felt if it was on the air, it had to be true.

In an essay entitled “The Great Martian Invasion,” writer Ann Elwood went even further in her analysis of the public state of mind in 1938. In her story, she asked: “Was it just the play that caused the panic on that October night? Or was it something else for which the Mercury Theatre broadcast served merely as a catalyst: a combination of the anxiety and tension permeating a world on the brink of war (or) the low mental defences of a people exhausted by the Great Depression…”

Years ago, I interviewed the producer of the War of the Worlds broadcast. John Houseman claimed the entire radio station and cast were in on the hoax.

“We weren’t pulling one over on the network. CBS knew what we were doing. We read the script over and then Orson (Welles) took over and directed it brilliantly.”

But when I asked him (back in 1978) if a similar hoax could be repeated on contemporary media, he answered definitively,

“No. This could only have happened on radio.”

Ultimately, the last laugh that October night in 1938 went to the show’s directing mastermind, Orson Welles, as he stepped out of character in the final moments of the broadcast.

“Remember the terrible lesson you learned tonight,” Welles concluded. “That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch. And if your doorbells rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian. It’s Halloween.”