As a boy, not surprisingly, he joined the scout movement. He loved to listen to the wireless radio broadcasts that came all the way from the BBC in England. But in every other way Jan Van Hoof was an ordinary Dutch boy during the Second World War. That is, until Sept. 17, 1944. During the next 24 hours, as Allied paratroops descended through the skies over his hometown of Nijmegen, Van Hoof left his youth behind. And it was summed up in what he said to his parents that day.

“The bridge is safe,” he said.

The steel-girder bridge, one of the longest spans in Europe at the time, traversed the River Waal. Consequently, it just happened to be the second of three river-crossing objectives that the Allies had chosen to capture and occupy as part of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s infamous Operation Market-Garden in September 1944.

But the Germans, who had occupied Holland since 1940, anticipated an Allied attempt on the bridge. They had quietly hidden 2,000 pounds of high explosive in its superstructure to ensure the bridge would never fall into Allied hands. That’s when young Van Hoof took it upon himself to sneak into the bridge girders and cut the ignition wires on the explosives. Because he took that risk, the Allies were successful and took the bridge the next day, Sept. 20, 1944. A boy became a war hero overnight.

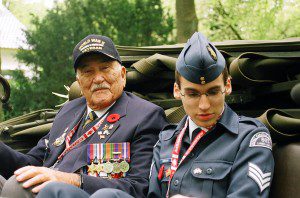

This week, I have led a group of 40 tourists to the celebrations recognizing the liberation of Holland 65 years ago – in May 1945. A number of those Canadians travelling with me, like Jan Van Hoof, gave up their innocence and boyhood pursuits during that same period.

Among them is Ron Charland from the eastern townships of Quebec. He served with Le Regiment de Maisonneuve. Just a 20-year-old private, “Frenchie” as he is affectionately known, served as a sniper throughout that last winter of the war. Employing only his wits and his Lee Enfield sharpshooting rifle, he searched for German targets in the front-line area between his regiment and enemy positions in eastern Holland.

“The worst part was,” Charland said, “you’d be out in that no-man’s-land – alone – for 48 hours at a time.”

It was in the same part of that Dutch countryside, as the Allies began their last push into Germany, that Charland lost a buddy. On the third day of our liberation tour this week, I watched Frenchie search the Canadian War Cemetery at Groesbeek ’til he found the grave of Pte. Eduard Paquette, killed Jan. 23, 1945. He was only 21. I watched Charland crouch his 6-foot-1-inch frame at the grave site, place a Canadian flag there, and then give an emotional last salute.

“Probably the last visit I will ever make,” he said just audibly.

Not far from Frenchie’s final tribute to his friend, another Canadian made his way to the Ceremony of Remembrance at Groesbeek cemetery, Monday afternoon. Born in Holland in 1935, Thornhill resident Albert Vrensen has been overcome several times this week. Most notably when we visited the National Liberation Museum (also in Groesbeek), I saw Vrensen visibly shaken by archival photographs of German troops invading his childhood hometown, Rotterdam.

“That was 1940,” he said. “I remember later that Hitler’s car drove past us. He was a mere seven feet from where I stood.”

Too young to join the Dutch Underground (as Jan Van Hoof had), Albert Vrensen, recalled an instance when a young resistance fighter shot and killed a German soldier. To set an example, the Germans summarily dragged people from their homes and executed them in front of horrified neighbours. All these years later the memories of such atrocities brought tears to his eyes. To make matters worse, Vrensen said his aged father died of starvation in the last winter of the war.

“My brothers and sisters and I almost didn’t make it either,” he said. “We looked like those images we saw years later of starving Biafrans.”

Albert Vrensen and his family managed to survive until the Allies finally liberated Rotterdam. After a period in the Dutch army, he immigrated to Canada. This return trip has been a first.

This week, Albert Vrensen, Ron Charland and others with me on this tour lamented what war cost the youth a generation ago. But then, Al and Ron survived to return for the 65th anniversary of peace and freedom restored in Holland. Frenchie’s friend Paquette wasn’t so lucky.

Nor, it turns out, was Jan Van Hoof. Just 24 hours after defusing the German explosives on the Nijmegen bridge, Van Hoof guided a British army jeep near Nijmegen. He was shot and killed in a German attack – Sept. 19, 1944 – and instantly became a martyr of the Dutch liberation.