He helped save Canada.

Aside from times during the two world wars, I think some of this country’s darkest days occurred in the years immediately following the Centennial in 1967. First with the St-Jean-Baptiste riots and bombings in Montreal (1968), then during the October crisis (1970), when the FLQ kidnapped and killed cabinet minister Pierre Laporte in Quebec City, hope for maintaining a united Canada seemed bleakest in those early 1970s.

Then, in November 1976, the Parti Quebecois came to power on a platform that included Quebec’s separation from Canada. I worked as a radio producer/host for CFQC in Saskatoon in those years. Our morning program was heard all over the three Prairie provinces. And I remember our station manager, Dennis Fisher, calling us together soon after the PQ’s historic victory that autumn.

“The nation has never been so threatened,” he said. “It’s up to us to do something.”

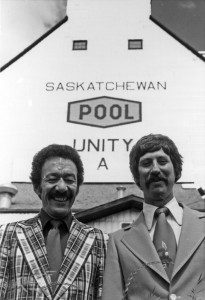

I remember looking around the room at my radio colleagues. Most of us were young, new in broadcasting and (situated in the middle of the Prairies) feeling as if we were a long way from the centre of decision-making and a long way from having any influence over the potentially divisive events unfolding in Quebec. Our two morning show co-hosts – Denny Carr and Wally Stambuck – were seasoned broadcasters. They certainly knew a lot of people, but even they admitted feeling helpless over the events about to change the very makeup of Canada.

“What if we broadcast a show of unity on Canada Day?” Fisher suggested to us. “What if we invited people from all across Canada to tell Quebecers how we care about them on our program? And what if we stage our Canada Day show in a place that epitomizes our message?”

Carr and Stambuck and the rest of the station staff wondered what Fisher had in mind. Was he planning to move the show to the national capital, or maybe to Quebec? No, he told us, the show would bring proud Canadians – by phone, by letter and in-person – to a town of 2,000 residents about an hour’s drive west of Saskatoon, near the Alberta border. The “Wal and Den Show” on the upcoming Canada Day only – July 1, 1977 – would be broadcast from Unity, Saskatchewan.

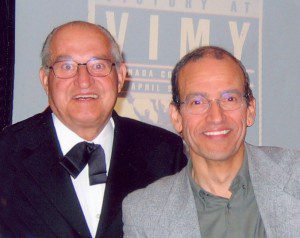

Dennis Fisher was born and raised on the prairies. He first worked professionally as a draftsman, but in the 1960s moved into broadcast sales and management at CFQC, a private radio station run by the Murphy family of Saskatoon.

Even more than his station manager’s job at QC, Fisher loved the stories from his part of Canada. He took great pains to investigate and preserve Aboriginal stories from the prairies. He had a vast network of pioneer and veteran friends. And he knew more about the Riel Rebellion than anyone I knew. In fact, I met Dennis, when he knew I was compiling a book about captains, pilots and pioneers who’d participated in steamboat commerce on western river systems of the late 19th century. One day, he invited me to his office, where he revealed a red, leather-bound journal. It was the diary of Louis Riel.

“It contains Riel’s notes about rebellion,” Fisher told me. “He even describes his plan to capture a Canadian steamboat on the Saskatchewan River.”

For a novice researcher/historian, this was a gold mine. What’s more, Fisher would often take me out to Batoche – where Riel had made his last stand against the Canadian militia forces of Gen. Frederick Middleton in 1885. There, before the first sprouts of green grass poked up through the Prairie earth, Fisher would share with me his discovery of Gatling gun shells, cannon fragments, jacket buttons and even debris from the home of Riel’s military strategist, Gabriel Dumont.

There were days when the station manager and its busiest producer disappeared for hours because Fisher wanted to show me another artifact he’d discovered from the early days of Saskatchewan history. He even arranged an exclusive interview for me with former prime minster John Diefenbaker to share his views of Canada.

In fact, the day our Canada Day broadcast went to air – from 9 a.m. until noon, July 1, 1977, in Unity, Saskatchewan – we managed to include the personal messages of three Canadian prime ministers, all 10 provincial premiers, industry and professional leaders from coast to coast, and hundreds of Prairie listeners – all expressing their ideas for a united Canada.

Alan Blakeney, then premier of Saskatchewan, even flew in for the occasion. He arrived in time to offer his personal wish to keep Quebec in Canada and to cut a huge July 1 birthday cake, shared by the residents of Unity.

“It’s been a great 110th birthday for Canada,” our two hosts on-air said as the show wrapped up this uniquely Canadian broadcast.

They were right. That day, the country’s leaders and its average citizens had been invited into the limelight to express what they had only quietly felt, but had rarely expressed. It took a thinker with foresight and conviction, Dennis Fisher, who spoke with his stature as a broadcaster and his passion for Canada’s past, to give its future a voice.

Ted….what a wonderful memory!!! Dennis must be so proud. Congrats on an incredible piece of Canadian History;the “Unity” show AND on being awarded the Citizen of the year. Denny would be so proud as well.

Regards from my new job,

CEO

Saskatoon City Hospital Foundation

looking for info on the history of the murphy family owning raadio station saskatoon

Can you tell me what the “QC” in Radio station CFQC means. I always thought it was Queen City but that is Regina’s nickname. I remember visiting my grandmother many times a year as a kid in the late 60’s early 70’s and fathfully listening to Wall n’ Den on the radio.