On Nov. 16, 1860, George Davies made history. The lighthouse keeper climbed the newly constructed, 15-metre-high, conical tower of Fisgard Lighthouse at the entrance to Esquimalt naval harbour on Vancouver Island. His appointment not only helped the British claim sovereignty of the Pacific Coast, it also made a statement about public investment in literacy. In addition to his salary for the nightly lamp lighting atop Fisgard, keeper Davies received a $150 stipend to purchase magazines and books.

“It is of the utmost importance to the interests of the Lighthouse Service,” the Governor of Vancouver Island stated at the time, “that the minds and intellects of the lighthouse keepers should not be allowed to stagnate in their isolated and … desolate stations.”

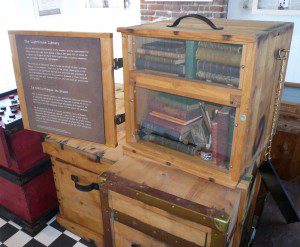

Friends my wife and I have been visiting in Victoria, B.C., took us to Fisgard this week for a scenic picnic and a taste of Pacific history. The view from the lighthouse to the Straits of Juan de Fuca and the Washington mountains proved spectacular. But the encased books of the lighthouse keeper’s former library struck me just as much.

For its time, the book stipend seemed an enlightened decision. The policy of budgeting funds for reading material showed clearly the progressive view that working people – no matter their stations in life – should have access to the literature of society.

By coincidence this week, in my work with the Writers’ Union of Canada, I’ve read about a federal government decision that represents just the opposite attitude. About a year and a half ago, the national archives, Library and Archives Canada (LAC), announced a total moratorium on the purchase of books for its collection.

At the time (June 2009), Doug Rimmer, assistant deputy minister of programs and services at LAC, told CBC News the moratorium was temporary. It did, however, put the brakes on a $1-million-a-year expenditure and, as a consequence, stopped a lot of buying and potential royalties going to authors. Rimmer cited the rapid increase in digital content as a reason for re-evaluating LAC’s investment in books.

“We have a responsibility to ensure that we’re using our money as effectively and efficiently as we can,” he told the CBC.

Among those awaiting both the end of the moratorium and LAC’s next move are Canada’s buyers and sellers of antiquarian published material. This week, I spoke with Liam McGahern, partner in Patrick McGahern Books in Ottawa and the president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Canada. He informed me that the LAC moratorium is over, but that the national library has now no budget at all to purchase books – Canadian or otherwise.

“In a good year,” McGahern said, “we have sold between $10,000 and $30,000 worth” of books, letters, maps and photographs to LAC. “We’re glad the moratorium’s been lifted. But where did the [$1 million] go? Maybe we’ve all been too accepting of this [government] review process.”

In other words, he said as an example, if his store were to acquire a rare first edition of W.O. Mitchell’s “Who Has Seen the Wind” inscribed to his son, because LAC has taken this stand on digitization and budget cutbacks, the Mitchell edition would almost certainly go to a private (probably U.S.) buyer. It wouldn’t benefit Mitchell’s estate and certainly not Canadian booklovers or researchers.

“LAC is saying the original, printed document doesn’t matter. It’s saying it’s acceptable to have a facsimile,” McGahern said. “That bothers us, as it does Canadian authors and readers. We feel we play an important role in building Canada’s national collection.”

Remarkably, like the government agency that oversaw the Fisgard Lighthouse and supplied its keeper with access to literacy in 1860, early residents of Uxbridge benefited from equally enlightened public thinking. Look at the community’s nearly 125-year-old library and realize that one of the town’s earliest Members of Parliament made much the same kind of investment in literacy.

In 1887, MP Joseph Gould helped fund the construction of the Mechanics’ Institute building in Uxbridge; with money left over, Gould added an endowment to fill the Institute’s shelves with books for public use.

“This building is the first donation of the kind in [Ontario,]” the provincial minister of education said in 1888, “and is the best in the province for the size of the town.”

The disappearing $1 million budget at LAC may not appear consequential on the grand scheme of book publication and literacy in Canada.

But in an era when information of all forms should benefit all Canadians, it appears LAC’s and the federal government’s hesitation to invest in books is counter-intuitive.

Like Vancouver Island without a Fisgard Lighthouse, such decision-making runs the risk of leaving Canadians adrift in the dark when they most need a beacon for knowledge and identity.