On a hypothetical day, responding to downtown apathy, the township votes against redeveloping the main street. Or, guessing about a population shift, the public school board makes plans to dismantle one of the town’s elementary schools. And then, wildly projecting buyer trends, several of the big-box stores in town decide to forgo sales for gardeners, truck enthusiasts or on Boxing Day.

In these make-believe scenarios, the municipality, the board and retailers are quite happy to ignore information readily and often freely provided by Statistics Canada in its regular written census. They would agree with the current Industry Minister’s perception that Canadians can do without the long-form census.

“The state has no right to demand intrusive information,” Tony Clement told reporters, and further that “up to 24 per cent of Canadians believe [they] should not be forced to answer it.”

Well, my three hypothetical scenarios and the industry minister’s sense of Canadians’ preference appear to be equally false. Neither can public administrators, educators or successful members of any community business operate without the valuable data the Stats-Can census provides, nor can the federal minister reach such apparently unfounded conclusions.

Are you among the 24 per cent? Did you feel that Ottawa was being too nosey the last time you filled out your mandatory long-form census questionnaire? Is this really a privacy issue for Canadians? I wonder. My guess is that if you asked the Uxbridge Township office, the Durham Public School Board or the businesses along Toronto Street South, they would say “no” on all counts. The census is not intrusive. It’s imperative.

I barely remember the last census form, let along feel put upon by it. It probably took me 20 minutes to complete it. It asked me about the size of my house – yes, including the number of rooms – and who was living there. In our case, because our two daughters had recently married and moved to houses of their own, these seemed pretty logical questions to ask.

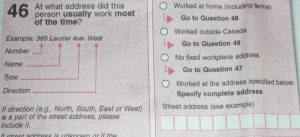

It asked me where I lived and where I worked and therefore – as a commuter – probably deduced I might require some means of travelling to and fro – private car or public transit. I figure these are pretty legitimate aspects of my life for which I can/should provide data.

And so too do Canadian public administrators, charities, business operators, social services and future planners. Agencies such as the City of Toronto, the United Way, Meals on Wheels and even the Fraser Institute (a fiscally conservative and often vocal supporter of Harper administration’s policy) have all expressed their opposition to the federal government’s plan to scrap the long-form census.

Apparently, one of the reasons the federal government has a problem with the long-form census, comes from its estimation of the public’s desire for privacy. The Conservatives believe that the census questions are intrusive. This, when all the world – from airport security scanners to the public’s compulsion to tell all on Face Book – seems bent on revealing everything to everyone without a second thought. I am a firm believer in keeping certain things private.

My wife and I, for example, see no need to show airline or security officers a passport, when a driver’s licence will do. And I routinely refuse to give out my postal code just because a retailer would like to know where I come from. But the national, public, long-form, written census form, I believe, provides the fundamental details of life that in return will continue to improve its quality.

I remember the Order of Canada ceremony at Rideau Hall in Ottawa in the fall of 1999. There, in addition to my father, Ivan Peter Fellegi – the man who had piloted Statistics Canada for some 40 years – stood before Governor General Romeo Leblanc; Fellegi was finally being recognized.

He had worked in virtual anonymity compiling, collating and computing the data of Canada so that those responsible for supporting and servicing a country’s daily life could operate with knowledge – not ignorance – of its population’s desires and needs. Apparently, Rideau Hall had recognized a valuable service and rewarded its provider.

Finally, let me put this discussion in terms the current federal government can understand. Abolishing the long-form census is kind of like General Motors designing the next prototype automobile without any R and D, without knowing who might buy the car, and without costing out the car’s components. Who’d buy anything from that kind of organization?

Or, like the Bank of Canada creating a $3 bill without consulting the Mint, Canadian retailers or the public. Cancelling the census form is like issuing a $3 bill. Makes no sense.

By the way, Angus Reid, another respected census user, last week released its own take the issue. It said more than half of Canadians believe the federal government should reverse its decision and maintain the mandatory, long-form census.