I remember the day some business friends and I needed a room in which to meet. A financial advisor friend offered his offices. As I sat down in his boardroom, I spotted a large picture frame on the wall. It contained several images of the former post office in my town. It was typical of that turn-of-the-century, Edwardian construction – tall central tower, large windows, red bricks. When I asked what had happened to it, someone said they’d torn it down.

“Any chance they’d ever rebuild something like that?” I asked naively.

“No will. No way,” fellow board members told me.

Let me tell you about the will to rebuild. Come to Eastern Europe as I have this past week. In the past 70 years – and in particular since the Berlin Wall and East Bloc Communism tumbled in 1989 – no other place I have ever seen illustrates that will better. I am currently touring Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic, planning a tour here next spring to explore this part of the world for its wartime history and other unique attractions. I’ve discovered one that epitomizes what it means to rebuild from scratch.

It all began the night of February 13-14, 1945, during the Second World War.

Taking off from British aerodromes that night, nearly 800 Allied bombers set out for destinations deep in Europe. About 250 of them flew to Dresden targeting more than 120 wartime factories. George Mitchell, an RCAF veteran friend of mine gave me details of the legendary attack.

“Altogether 881 tons of bombs fell in the central districts of Dresden between 10:13 and 10:28 p.m.,” Mitchell wrote. “By 11 p.m. the [city] was burning so intensely that it was too much for the city force of a thousand firefighters… Most people then thought it was all over…

“At 1:07 a.m. the air raid sirens sounded again … A second bombing [took place] from 1:21 to 1:45 a.m. The fires could be seen 50 miles away.”

In addition to the destruction of military targets, tragically more than 20,000 people died in the resulting 1000-degrees Celsius firestorm. Equally unfortunate, the 18th century, 100-metre high Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) was destroyed.

“Fire erupted inside the church at 2 in the morning,” church historians reported. “The organ too was engulfed and the tin of the organ pipes melted. When the organ loft collapsed, it fell on the lower altar area, shielding it enough for some of the altar requisites to survive undamaged.”

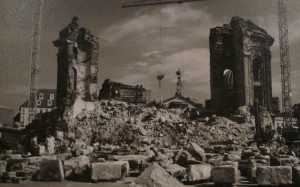

Except for two stair towers of stone on either side of the church, 6,000 tons of the Frauenkirche structure tumbled into a mountain of debris. And there it remained until the Berlin Wall come down in 1989, when enthusiasts began a public awareness and fund-raising campaign to resurrect the church.

From a handful of musicians originally to a city-wide (and eventually worldwide) campaign, those sympathetic to rebuilding the church raised 180-million Euros (including U.S. doctor Gunter Blobel who donated his entire $1 million Nobel prize). But that was only half the unique story.

Beginning in 1991, archaeologists scoured the 70-metre-square pile of rubble and like a jigsaw puzzle they marked with metal “dog tags” and catalogued each of the 8,500 stones they found. Then, based on photographs, memories of worshippers and something called “photo-electronic stocktaking,” nearly 3,800 of the original stones and thousands of new replicas were laid one-by-one, beginning with the foundation stone in 1994.

In 2003, work began on the cupola, topped with a gilded cross the next year. New bells rang from the belfry and pipes sounded from the organ loft in 2005. Workers completed the job in 2006, in time to mark the 800-year anniversary of the City of Dresden.

And that’s key, because as was pointed out to me, Frauenkirche was rebuilt not so much for religious reasons, not just as a remembrance of those lost in the war, nor even as a symbol of reconciliation between former warring enemies.

“A city functions very often based on its landmarks,” my guide friend René Thied told me this week as we toured the restored church. “People say, ‘Let’s meet at the Frauenkirche.’ So landmarks keep people connected, a community functioning.”

Thied pointed out that the same was true in Berlin, particularly since the wall came down in 1989. Even though much of the rubble left by the Second World War and 50 years of the Cold War remains in parts of the East, he said, cities in Germany have tried to rebuild squares, restore monuments, or even incorporate ruins (such as the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedachtniskirche) to give populations (literally and figuratively) touchstones.

It’s a form of resuscitating a community’s heart that some New World communities, even as small as Uxbridge, can learn from the Old World.