The other night, I sent a couple of dozen of my journalism students out into the night. They had to go to one of the municipalities where the public was voting for mayors, councillors and/or aldermen. Their job was to get the perspective of the loser and the reaction of the winner in their chosen ward for the record. The reaction I got from one or two members of my class of practising reporters amazed me.

“Why is it so important to do this?” one student asked.

“Because I can actually remember a time in Canada when I couldn’t cover a political story,” I said.

Now, some of my students think I was raised and educated when the earth was still cooling. And, in fact, the incident I went on to describe to them actually took place 40 years ago. But I think it made the point very clearly. Never does the 10th month pass each year without my remembering events in Quebec in 1970.

That was the year members of the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ) kidnapped James Cross, a British trade commissioner, in Montreal. They then demanded money, safe passage to Cuba, the release of 23 detained FLQ members (some previously convicted of bombings, holdups, manslaughter or murder) and the broadcast of the group’s manifesto in return for Cross’s release. I remember the voice of Radio-Canada announcer Gaetan Montreuil reading the manifesto over the CBC.

“We will always be the assiduous servants and the boot-lickers of the (English-speaking) big shots,” the document admonished.

Minutes after the Quebec government of Robert Bourassa refused the rest of the Front’s demands, on Oct. 10, another FLQ cell kidnapped Pierre Laporte, the vice-premier and labour minister in Quebec. Overnight, this distant and disorganized protest group seemed immediate and threatening.

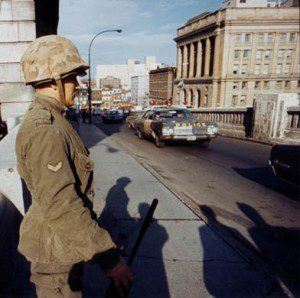

The federal government called out the army to protect politicians, corporate buildings and the Quebec National Assembly. Prominent Quebecers held a press conference announcing that, “Quebec no longer has a government.” On Parliament Hill, CBC reporter Tim Ralfe questioned how far Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau might go with his police-state tactics and he famously uttered the phrase: “Just watch me!” Shortly after, Trudeau imposed the War Measures Act (WMA), which effectively suspended all public civil liberties and Laporte was found murdered.

“The guns pointed at the heads of (Cross and Laporte) have FLQ fingers on the trigger,” Trudeau said on national television. “The government promises unceasing pursuit of those responsible.”

Throughout the tense days of the kidnapping, I went about my second year studies in Ryerson’s Radio and Television Arts program. To gain a bit more experience (and a few extra dollars) I hosted an all-night music and talk show on Ryerson’s broadcast outlet – CJRT-FM (later 91.1 JAZZ-FM).

As the Friday and Saturday night show host, I had a pretty high opinion of myself as well as my music and interviewing skills. One night at a party, I met a man who’d been caught in the dragnet of the WMA and then released. It seemed to my inexperienced journalistic instincts to be a natural reaction to invite him to my show and query him on-air live about Quebec under the WMA.

“Tonight I have an exclusive,” I remember telling my audience. That audience included a number of friends and media colleagues who expressed palpable panic over the events in Quebec. One friend in particular thought the country was on the verge of civil war and she wondered where we might go if fighting came to the streets of Toronto.

It turned out by exploring the kidnappings and arrests of civilians on the air, that I was violating the WMA. It clearly stipulated that outside of newscasts, covering any aspect of the crisis was not allowed. What I didn’t realize was that the WMA effectively imposed martial law and removed all civil rights – free speech, rights of assembly and the freedom of the media.

Of course, I wasn’t aware of that at the time and since there were no repercussions, I guess I’ve discovered how few listeners I must have had back in those tense times.

No matter how many or how few listeners I had on the air that night, however, I learned an important lesson in October 1970: Never take lightly the civil liberties this country has enshrined deeply in its federal statutes.

No matter how deeply, no matter how enshrined, politics of the day can very easily take those liberties away. That’s why I made sure every student reporter in my journalism class exercised the freedom of the press to cover the election Monday night.

No right is too sacred it can’t be taken away.