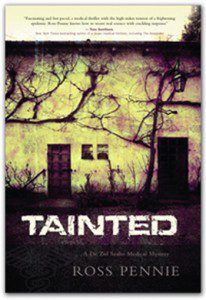

In his 2009 book “Tainted,” Canadian author Ross Pennie explores the hypothetical likelihood of a regional health facility facing a sudden outbreak of mad-cow disease in a small Ontario community without any apparent explanation. The book is a thriller, an entirely fictionalized depiction of a system facing a medical crisis and widespread public panic right in our own backyard.

In his 2009 book “Tainted,” Canadian author Ross Pennie explores the hypothetical likelihood of a regional health facility facing a sudden outbreak of mad-cow disease in a small Ontario community without any apparent explanation. The book is a thriller, an entirely fictionalized depiction of a system facing a medical crisis and widespread public panic right in our own backyard.

But Dr. Pennie admitted to me – and the audience watching our interview at the Whitby Pubic Library, Monday night – that he didn’t write this medical mystery as a slam against doctors or Canadian health facilities. No, he said, it was, in a way, medical teaching universities he was decrying.

“I’m not criticizing doctors or the medical system,” he said, “but I am knocking those in academe who would rather drag each other down than see any one individual scientist get credit for advancing the cause of medicine.”

I found the moment a rather stunning one. His plot line and characterization in “Tainted” were strong enough to make most of us squirm with discomfort at the mention of infectious disease pandemics. Mad-cow disease (or Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease) breaking out is hideous enough a concept to imagine; and in fact it did occur in Britain a few years ago.

And indeed, Dr. Pennie had seen CJD close up during his two years serving the native population on the South Pacific island of Papua New Guinea. But here was an otherwise mild and gentle man, who had perhaps spent more time in the esteemed halls of higher learning than most medical professionals (outside of medical school), calling down the teaching world in which he has spent a majority of his life.

Among other highlights in a colourful medical career, Pennie has coped with outbreaks of malaria and tuberculosis, conducted surgery in the middle of an earthquake, and worked in a society that accepted cannibalism as a form of last rights for its ancestors. All that had occurred when he was in his 20s back in the 1970s and became the foundation for his first book, “The Unforgiving Tides.”

But after his volunteer service on Papua New Guinea, Pennie had come home to North America and spent the bulk of the next 30 years studying, then teaching, evaluating and lecturing to medical students in paediatrics and infectious disease research in such places as Charlottesville, Virginia, and Fortaleza, Brazil, as well as the University of Ottawa and McMaster University in Hamilton.

He called his medical career “an adventure.” He called his desire to write books based on it “a personal writing journey.”

But I was transfixed by his conviction that some doctors at teaching hospitals in this country could be capable of sacrificing a potential medical breakthrough – maybe even life-saving products and procedures – in favour of personal profit and professional interference. Pennie seemed adamant that behind some medical university walls was an evil that had to be exposed. Then again, when I thought about it, I guess I realized that medical teaching wasn’t the only potential place for such human shortcomings.

After all, politics, religion, business and the arts are equally susceptible to such character flaws. All one has to do is watch a political campaign such as the most recent municipal campaign in the GTA to recognize how cutthroat winning and losing can be. It only takes example of the looming hostile takeover we’re witnessing at the Saskatchewan Potash Corporation (by BHP Billiton) to sense the one-upmanship that’s rife in some corporate board rooms. And as gentile as they may seem, I’ve no doubt the upcoming announcements of such Canadian literary prizes as the Giller and Governor General Literary Awards will witness just as much envy and false magnanimousness as might be found at any post-secondary teaching school.

I guess if you scrape at the surface of any workplace or social activity, you will find basic human aspirations and fears at play, avarice not the least among them. The question I guess we often aren’t willing to face – the way Ross Pennie tries to in his latest novel – is how long do we allow those human frailties to circumvent human decency and honesty?

Actually, as I write this column, I am reminded of the story a former ambassador once cited from the writings of Canadian literary giant Northrop Frye. Frye apparently told the story of a Canadian Maritime fisherman carrying a pail of lobsters up from the wharf.

“Hey, there’s no lid on your bucket,” another fisherman warned him. “The lobsters might escape.”

“Oh no,” the first fisherman said. “These are Canadian lobsters. As soon as one makes it to the top, the others will drag him back down.”