In the days following 9/11, the West had revenge top of mind. Within days of the terrorist attacks, U.S. President George Bush promised his armies would avenge the deaths of the 3,000 Americans killed, claiming that the perpetrators were “Islamists commanded to kill Christians and Jews” and that they were therefore “wanted dead or alive.” Most in North America accepted his Wild West form of justice.

At the time, however, a professor at Concordia University in Montreal did not. Almost at his peril, journalist and educator Ross Perigoe criticized the powers that be, in particular the Montreal Gazette, for what he called its racist response to 9/11.

“I am in the Place des Arts metro station,” Perigoe cited a Gazette editorialist on Sept. 19, 2011, “I see three men, one wearing a turban. I start to shake.”

The commentary infuriated Prof. Perigoe. He reacted by researching, interviewing and then publishing his response as part of his PhD thesis in 2005. In part he wrote: “The courageous thing to do would have been to have fought the tendency to lash out at the nearest people – Muslims – who were completely blameless.” Remember, the culprits of the 9/11 attacks were not Afghans, nor Iraqis, nor in the truest sense Muslims, but Saudis bent on terrorism above all.

Last Thursday at Ross Perigoe’s funeral, the professor’s son, Evan Perigoe, a law school graduate, remembered his father’s commitment to speaking out for minorities. Ross Perigoe, 62, had died of cancer on Jan. 4.

“He taught me to work hard, have fun and speak truth to power,” Evan Perigoe said eulogizing his father. Coined by American Quakers, “speak truth to power” was the motto of outspoken liberals confronting conservative thinking in the U.S. in the 1950s. For Perigoe’s two sons – Evan and Clarke – the call to action half a century ago represented their father’s life-long raison d’etre.

“My father was uncompromising,” his younger son Clarke Perigoe said. “He led by example and for that he will never be forgotten.”

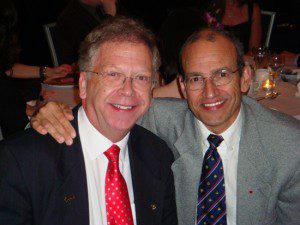

I will never forget Ross Perigoe because he was my oldest and closest friend. We met in 1956 when we were both seven and when my family moved next door to the Perigoes in Agincourt, Ont. After that, he and I did almost everything together – attended the same elementary and high schools, and then enrolled in the same Radio and TV Arts program at Ryerson in the 1960s. That’s where Ross Perigoe (and I) experimented with speaking truth to power. Among other projects, he and I co-produced a series of pointed documentaries for CBC Radio – on noise pollution, rock festivals and dishonesty in advertising. Remarkably, the CBC aired them and gave us an entrée to public affairs journalism.

But Perigoe never stopped advocating and broadcasting critically, especially when he began teaching journalism at Montreal’s Concordia University in 1985. Among other topics, he revealed the problem of journalists traumatized by violence; he examined the censorship of the Japanese-Canadian press during the Second World War; and, with his wife Christina Perigoe, he explored the special needs of children with hearing loss. In 2009, the Radio Television News Directors Association awarded Perigoe an award for excellence in broadcast teaching and mentorship. It was overdue recognition for a quarter century of teaching and inspiring up-and-coming TV anchors, investigative reporters and documentary makers to speak their truth.

But Perigoe also lived by that second ethic noted by his sons at the funeral – to have fun. In 1970, while still attending Ryerson, Perigoe and I responded to a call for freelance writers. We arrived at the rented Etobicoke mansion of Hamilton TV producer Randy Markowitz.

“Tonight,” he announced to us beside his indoor pool, “you guys are going to create a unique children’s program.”

Perigoe and I looked at each other and then improvised out loud for three hours while Markowitz’s secretary took notes. That night, we invented the pilot program for what would become a children’s cult TV show – “The Hilarious House of Frightenstein.” It had few redeeming qualities except, like everything Perigoe put his hand to, Frightenstein defied all the rules and yet proved magically palatable. It married a smattering of education with what kids loved – monsters, castles and corny jokes. It became a hit and – believe it or not – we earned our wages and were paid $3 a joke!

“Ross had a remarkable sense of humour,” said Marnie Malcolm, Perigoe’s sister, at his funeral. “He could captivate you with his stories.”

She noted that in 25 years of teaching at Concordia University, her brother had enriched the learning of hundreds of journalism students with his knowledge of the profession and his passion for telling true stories. “It’s a great gift,” she said.

With Ross Perigoe’s premature death at 62, future Concordia journalism students will never receive that lecture hall gift. Nor will tomorrow’s vulnerable Canadians benefit from his advocacy journalism – speaking truth to power.

It’s tough to do justice to someone like the man you describe, Ted. But I think you’ve come close! Considering the tight bond between you and Ross, this was an impressively warm and clear-eyed rendering of a gifted man and the gift of your relationship. Thank you for sharing it. (And my apologies for misspelling Ross’ last name in a note to our colleagues last week.)