I don’t know which was worse: the hype over last weekend’s so-called sporting match in Indianapolis, the anticipation over the new 30-second commercials (reportedly costing US$3.6 million each for the airtime), or the guessing about what Madonna would do during her half-time show at the Super Bowl. The newspapers, magazines and TV commentators were all atwitter all week.

“Would she employ her thin veneer English accent?” one asked.

“Would she be naked?” hoped another.

My answer was a resounding: “Who cares?”

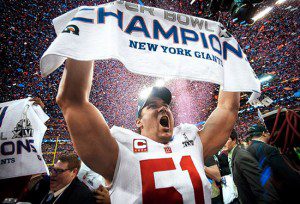

That’s just one example. You don’t have to look far, to see “celebrity” eclipsing real issues, real information or real stories, just because a so-called star’s involved. This week, the show-biz tabloids speculated about Jennifer Aniston’s unborn twins. The stargazing paparazzi caught Elvis Costello and Willem Dafoe carrying shopping bags in the fashion district. Fashion wags stewed over Karl Lagerfeld’s accusation that singing star Adele “is a little too fat.” And after the Super Bowl, it was more about M.I.A.’s finger flip than even Madonna’s show or New York’s victory.

Of course, the big buzz this week, on the eve of the annual music hype-fest, the Grammy Awards, was Whitney Houston’s death. The police spokesman’s statement was barely out of his mouth, last Saturday afternoon, when the spin for attention began. Was it drugs that killed her? Did she drown in her bathtub? And perhaps saddest of all: How much will her music be worth now that she’s dead?

The question I regularly ask myself and (these days) my news reporting students, at Centennial College, is: Why is that stuff news? I often tell them they need to use the filter of their training to decide whether a story deserves to be published/aired. I ask them to determine if a story meets certain criteria that consumers demand when they read, listen or view the results of their work. Is the story timely? Does it have relevance? What is the story’s magnitude or impact on the community or the world? How unexpected is it the event? Is there conflict? Does the story affect us emotionally? Based on that last criterion probably rests my entire argument, because if reporters and editors really believe Houston’s death affects us, then I guess that’s why it’s news.

Over the years, I have openly criticized fellow journalists and editors who, like the paparazzi, follow their sources as if they were prey. When I see poor judgement in “celebrity” stories, I shake the newspaper, bang the dashboard of my car above my radio or shout at the TV. I continue to expect reporters to use those filtering criteria before they publish/broadcast the drivel they call news.

To be fair, when I began reporting for radio and magazines in the late 1960s, I did my fair share of celebrity chasing too. I had stars in my eyes whenever I got the chance to interview, some of my entertainment and sports heroes too – people such as B.B. King, Wayne Gretzky, Maureen Forrester, Billy Harris, Burton Cummings, Bob Feller and Kris Kristofferson, among others. I admit, in those formative years of my career, that I often did not ask tough, risky and sometimes provocative questions.

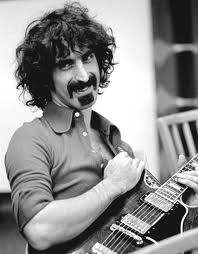

There was one exception. It was about 1970, during the period when the Masonic Temple in Toronto doubled as a rock music concert hall, called The Rockpile. Trying to break into underground radio at the time, I talked my way past a security guard at The Rockpile door and chased down rock musician Frank Zappa between sets in his dressing room. When I found him, he was clothed in a terry-towel robe, seated in a wing-backed chair with a gaggle of reporters poking microphones at him and asking him such mundane questions as: “What do you think of Toronto, Frank?” And “tell us about your latest album, Frank.”

I had prepared myself for this moment. I knew Zappa was full of vitriol about U.S. politics and foreign policy. The trick was to provoke him with just the right question. I waited patiently for the paparazzi and dumb reporters to finish. Then I stabbed my mike at Zappa and gave it my best shot.

“Why do you believe that Sacco and Vanzetti were scapegoats and railroaded to the electric chair in the 1920s?” I asked. I knew he felt the two known U.S. anarchists got the death penalty because they were immigrants and some American officials wanted to make an example of their radical sentiment. Well, Zappa took the bait and gave me five solid minutes of the best political commentary I think I’d ever heard. Unfortunately, the interview never got published or went to air. Nobody cared about Frank Zappa’s view of corruption in U.S. politics and jurisprudence.

Still I would put my amateur Q & A with Frank Zappa next to a discussion of M.I.A.’s finger flip at the Super Bowl any day of the week.