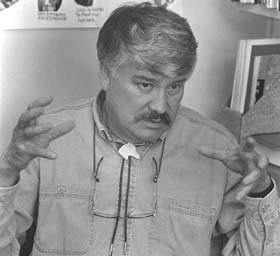

It’s about 30 years ago now that I met Elmer. Born in 1947, he was about my age. Like me he’d grown up searching for a place in the world to make a difference. He’d gone to elementary school in the Canadian North, to college to become an engineer and to university to study anthropology and political science. In the 1960s, he poked around Europe hoping to figure things out. Then he found his calling.

“My dad had taken sick and nearly died,” he said. “I decided it was time I returned home to get to know my parents.”

Home was a farm in a place called Paddle Prairie, about 500 kilometres northwest of Edmonton, Alberta. In 1939, Elmer’s father, Adolphus Ghostkeeper, had become the first farmer to break ground at the newly established Metis settlement there. Adolphus had started with 360 acres where he’d grown grain, raised pigs and horses, run a trap line and hunted moose for his family of 14 children. The 11th child was Elmer. But he was the first Ghostkeeper offspring to come home to the North.

Elmer Ghostkeeper has been on my mind this week because, perhaps like a lot of you, I’ve been wondering just how to figure out the turmoil among First Nations people. What was the point of all that posturing going on between the Prime Minister and the aboriginal chiefs? How did the hunger strike of Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence play into the discussions? What should the role of the Governor General be in all this? Where does the “Idle No More” movement fit in? And what, if anything, does the coincidental Federal Court announcement about Metis being considered “Indians” under the Canadian Constitution do to the picture?

It seemed to me that the kerfuffle between Stephen Harper and the National Assembly chiefs had more to do with jockeying for attention on both sides than it did about the health care, housing and supply of safe water to First Nations’ communities. I wondered about the intentions of Chief Spence’s hunger strike, when as one of my journalism students pointed out, a person can survive on that ration of fish broth. I hoped, as the Queen’s representative in Canada, that David Johnston could simply open up Rideau Hall to all the chiefs and just sit down for a civilized chat. But eventually I came back to the wisdom of my 1981 acquaintance, Elmer Ghostkeeper.

You see, when he went home to Paddle Prairie back in the mid-1970s, Ghostkeeper learned to speak his first language, Michif. Then, the Metis man learned how to become a spiritualist, a teacher as well as a learner, eventually a father, an entrepreneur and for the first time in his life a public figure; within a year of his return North, he had become the chairman of his Metis settlement, eventually winning election as president of the eight Metis Federation Settlements of Alberta.

Perhaps most important for his people – and I think for other Canadians – Elmer Ghostkeeper learned a new form of stewardship on the 360 acres of farmland he had inherited from his father.

“The land doesn’t belong to me,” he told me in an interview in 1981.” I belong to the land.” What’s more, he pointed out in his 1996 book, “Spirit Giving,” Canadians have to shift from living off the land to living with it. When he and I got to know each other, in those years in Alberta, Elmer was coming to the realization that aboriginal wisdom and what he called “Western scientific knowledge” needed to build on each other’s strengths and avoid each other’s weaknesses.

“Wechewehtowin,” is the word First Nations use to describe the process. It means “setting off together on a journey.”

There are some who will sneer at such phrases. They’ll say it’s just back-to-the-earth jargon and the mantra of the philosophical and political left. Perhaps, but if one looks at the kind of success Ghostkeeper has had drawing people to his creative thinking, it’s hard to argue.

In 1986, he established a mall corporation full of retail businesses in his home community of Paddle Prairie. In the 1990s he was elected fellow in the Arctic Institute of North America working on the preservation of Northern culture and habitat. He gained the confidence of large Western Canadian timber companies when he became business group leader of the Alberta Pacific Forest Industries. And when his community sought official status, he successfully lobbied the western premiers to secure recognition of the Metis in the Canadian Constitution.

“My daily challenge is to … live in the moment by incorporating yesterday’s experiences into a plan for today’s activities,” he says on his website.

As he was when I met him 30 years ago, Elmer Ghostkeeper remains a voice of reason and calm, amid the political photo-ops, railway blockades, environmental mismanagement and Parliamentary intransigence we see on TV and in the papers.

Hello Ted,

Long time no see. Hope you and your family are well.

I re-read this article today and you did a very good

piece of writing to capture the mood of Idle-No-More

movement and the politics of the day.

By any chance, have you read The Comeback by John Ralston Saul? Saul does good writing to capture the Aboriginal People’s progress during the last 100 years and speculates some to determine where it is going. It was a good read for me to put myself in context with Canada and Canadians.

Elmer