Outside the restaurant in Catania, Sicily, the young man and woman were listening to my conversation with Harry Watts. They overheard us talking about the liberation of their country, Italy. What made the moment rather special was that standing right in front of the young couple was one of the thousands of men who had accomplished that extraordinary feat, 70 years ago this summer. But the young couple seemed perplexed.

“We thought the Americans liberated our country,” the woman said.

“No,” Harry Watts said politely, but firmly, “this part of your country was liberated by Canadians.”

On July 10, 1943, the first of nearly 160,000 British, American and Canadian troops began the first concerted effort to liberate mainland Europe from the grip of fascist dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. The first step, Operation Husky, included 26,000 soldiers of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, which initially liberated Sicily, then the southern provinces of mainland Italy, and eventually the cities of Rimini, Ravenna and Rome.

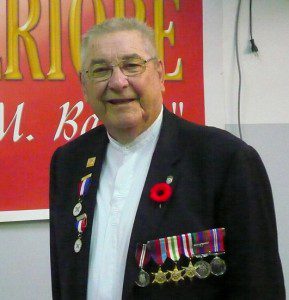

My veteran friend, Harry Watts, joined the First Div at Naples in the fall of 1943. But he felt comfortable speaking on behalf of all Canadians serving in that liberation force seven decades ago. Indeed, on Monday of this week during an assembly at Secondaria Superiore Michelangelo Bartolo (high school) in Pachino, Sicily, not far from where the Canadians landed in July 1943, former dispatch rider Harry Watts answered questions from the students. One of the students was Marco Rudilosso.

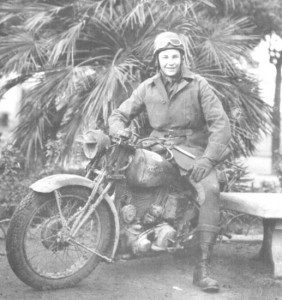

“Why did you decide to become a dispatch rider?” Marco asked.

“Because I was lazy. I was like a king seated on my throne, my motorcycle,” Harry quipped. But then he added, “I carried messages that were too top-secret to be delivered by telephone or telegraph.”

In fact, there was little about laziness or kings in his chosen wartime service. When the Canadian Army pushed its way to a showdown with German paratroops at Ortona, on the Adriatic coast, around Christmas 1943, Watts and his Norton motorcycle became a lifeline on two wheels. Every other day, it seemed, the Canadian was motoring his way along dirt paths, by bombed out towns, through mountain passes, in all kinds of inclement weather. He routinely left Naples at 8 o’clock in the morning, travelled 250 kilometres northeast, and arrived at Ortona late in the afternoon with his military messages.

On most of those cross-peninsula trips, he rode alone. But even in remote areas, there was always the danger his bike might break down, a tire might blow, or a German sniper might spot him. Once, Watts explained, he came to a washed out road with only truck and tank tracks through it. Fearlessly but cautiously, he sped through the mire only to meet a Canadian Army photographer on the other side.

“I missed your crossing,” the cameraman said. “Would you mind doing it again?”

“Sure,” Harry said. “Stay there. I’ll be going back the other way in a few hours.”

Men and women who served Canada during the Second World War often talk about living life on the edge, or as if there were no tomorrow. But Canadians carried with them more than a sense of respect for comrade and enemy. In Italy, Harry Watts indicated, the soldiers’ responsibility went beyond victory or defeat. It included community and (where possible) humanitarian service. In one Italian village the Canadians liberated, the civilian children were barefoot, their clothing in tatters. When Watts and his buddy Reg Cochran found out, they approached divisional headquarters about reprocessing old jeep tires.

“[We] cut them up in small pieces on a band saw,” Watts wrote in his memoirs, “and soon all the kids had something on their feet to keep them out of the mud.”

A few days later Harry Watts’s motorcycle travels took him to an Allied-liberated hospital in Rome (by this time Canadians had forced the capitulation of the Italian Army and had wrested the ancient city from the Germans). He informed hospital nurses that children in remote communities had insufficient clothing to get them through frigid conditions. He soon had scraps of Canadian Army uniforms and blankets repurposed into shirts, pants and jackets for the children.

“[The brigadier] came through one afternoon,” Watts said, “and thought we must have been running a black market in old Canadian uniforms. He soon got the message and said no more.”

Outside the Sicilian restaurant where Harry Watts and I met the young couple unfamiliar with the Canadians’ role liberating Italy, we pinned Canadian flags on their jackets. They went away chuffed they’d met one of their liberators. They thought his past was pretty impressive.

Well, so is his present. He’s still a valued member of the Memory Project, Friends of Veterans Canada, Canadian Army Veterans motorcycle riders and a Canadian Motorcycle Hall-of-Fame inductee. We passed a motorcycle parked in the street in Catania, Sicily, this week. I could see him salivate. He wanted to take it for a spin. Even on the eve of his 90th birthday, I’ve no doubt he could do it.

What a beautiful, evocative story about a man who is truly a Canadian hero. I loved reading this, and felt transported to Sicily along with you and Mr. Harry Watts. His indomitable spirit just shines through here. Thank you for the background on Operation Husky as well.