One spring weekend in 1967, I managed to convince several of my friends to accompany me to the family’s property in the country. The weather forecast promised to be sunny and warm. My mom promised some of her renowned Greek cuisine. My dad said he’d allow us a few beers at the end of the work day.

“Work day?” one of my friends, Michael Clancy, wondered.

“Yeah, just a bit of planting,” I said, “about two thousand evergreen trees.”

But by that time, my folks had comfortably locked my friends and me inside our family car en route to the 100-acre farm north of Pontypool on the west side of Highway 35. I had also convinced an area farmer to cut furrows (about six-feet apart) in the virgin sod on a hilltop at the farm. My plan was that my work crew and I would plant twice as many Scotch pines and blue spruce trees in those furrows as I had the year before (1966) in an adjacent field. I would thus become a big time Christmas tree farmer.

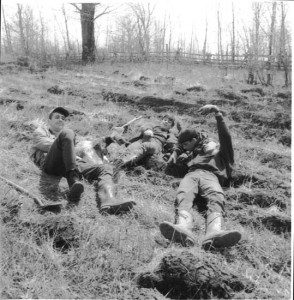

Two days of labour, several of my mom’s home-cooked meals and a few of those illegally dispensed beers later, we had planted all 2,000 trees. While they complained a bit, Michael, Colin Kaiser and Allan Bourne had helped me augment my Christmas tree plantation from 1,000 to 3,000 evergreens.

Now, around the same time – the mid-1960s – in that part of Ontario, many of the trees that lined those same farm fields in southern and central Ontario, were elms. These were truly elegant deciduous trees. Massive trunks with classically rough, ribbed bark rising in their maturity some 50, 60 and 70 feet to massive umbrella canopies comprised of proportional bows and plenty of lush foliage.

I describe them in this detail because many people younger than 30 or 35 will never have seen such a thing. You see, Dutch elm disease – a fungus spread by beetles – invaded Ontario in 1967 and killed up to 80 per cent of elms in the City of Toronto. Indeed, as I cultivated my pine and spruce tree plantation at the farm, our elms began to die around it.

“Fiddling while Rome burns,” is the expression that comes to mind.

If I had spent as much time investigating the potential to save those farm field elms as I did planting my evergreen forest, I might have saved some of the mature trees as the young ones grew. I learned later there was a treatment to save the elms. It was costly. It was painstaking. It was not always effective. But it was possible to have saved some of those majestic giants.

As evidence, by the time Dutch elm disease got to Manitoba in 1975, the City of Winnipeg had launched a program to treat the trees. Today nearly 200,000 elms remain in that prairie city. Albertans were even more aggressive and preservationist, as the province is disease free. In fact, when we lived in Edmonton during the late 1970s and ’80s, it was unbelievable to see so many disease-free elms.

“It’s like a flashback to the farm,” I remember telling my family.

Now, I tell these stories as preface to my feeling of discomfort over Uxbridge Township Council’s recent vote not to treat about a dozen of the mature ash trees threatened by an approaching infestation of emerald ash borers in Elgin Park. Unlike the Dutch elm disease plague of the 1960s, today there is treatment readily available to combat the ash tree infestation. It’s costly ($300 per tree per treatment); so was the anti-Dutch elm disease treatment. Nor is the $300 treatment a silver bullet. But I commend Coun. Jacob Mantle who quite astutely pointed out that the cost of chopping down the ash trees in Elgin Park tomorrow will likely eclipse what it might cost to inoculate them today.

For as long as I can remember – and we’ve lived in this community now more than a quarter century – people have always raved about Uxbridge’s unique tree canopy. In parks and along township streets and roads, we have enjoyed, even bragged about how green this place is. It’s one of our premier natural attractions.

But with recent dry years (as evidenced by dead zones atop some of our most picturesque park vistas) and limb losses in recent ice storms, this additional threat to our tree canopy can’t be taken lightly. Years ago I neglected the elms while planting my evergreens. I never did chop down those evergreens for cash; they remain there yet. But maybe my green-thumb effort missed the forest for the trees.

This week, everybody’s talking about the importance of royalty, respecting heritage and following traditions. Once upon a time, the jewel in the crown of this community was quite literally its tree canopy. If citizens and elected representatives take that heritage too lightly, I think it would be like being disrespectful to royalty. A blight not only on our skyline, but our reputation for respecting nature.

Good stuff, Ted.

Finally. A Branch Manager story that made me smile.

Though dead elms also appear in Italian paintings of the late 15th century, a link between these trees and Dutch elm disease remains largely speculative.