Everybody was buzzing about it. There had been a new arrival. We knew it was a boy. But nobody knew what he would be called. We were all breathless with speculation. Then after a couple of days, we saw the announcement from the parents on social media.

“All right,” the mother said by text. “It’s official. Tell the press and the paparazzi. We have a name…”

Oh, did I neglect to mention that last Wednesday evening, our daughter Whitney Ross-Barris gave birth to a seven-pound-two-ounce boy? I’m sorry. Were you thinking the “new arrival” last week was Prince George Alexander Louis of Cambridge? Actually, no. You see, two days after that other baby was born in London, England, our daughter and son-in-law Ian announced the birth of their son – a brother to Coen – in Toronto, Ontario. And like the new House of Windsor baby, the new Ross-Barris baby didn’t have a name for about 48 hours. But late on Friday, the announcement came through.

“From this day forth,” Whit told us, “the baby will be called Huxley Duncan Ross-Barris!”

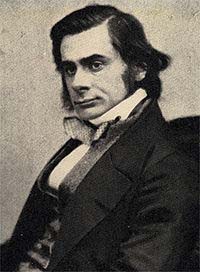

As it turned out, in the case of our new arrival, there were some additional similarities to the Royal arrival. The Canadian parents had thought long and hard about the naming of their newborn boy, much as Kate and William had. They considered names from their families’ past. They pondered their own experience together. They even considered some history. And so, the Royals came up with George (after Elizabeth’s father), Alexander (perhaps after Elizabeth’s middle name) and Louis (after Louis Mountbatten, Prince Charles’ great uncle). Meanwhile, the Ross-Barris parents came up with Huxley (after T. H. Huxley) and Duncan (after Ian’s grandfather).

And there may be more to the naming of our new grandson than perhaps was the case for the new Prince George across the pond… although the pond is actually involved. Contained in our daughter’s unique explanation of the naming of their son, Whitney recalled during her association with Ian, before they were married, that he needed to return to England to await the processing of his landed immigrant papers. Consequently, they were apart for sometime while the Canadian Department of Immigration examined his application to reside in Canada. It turned out that a difficult, but required, separation had kept British biologist T. H. Huxley from his betrothed back in the 19th century.

A naturalist in his own right, Huxley was largely self-taught in the study of invertebrates, fish, birds and mammals. At the age of 20 he passed medical exams at the University of London (1845), but was too young to enrol in the College of Surgeons, so became a surgeon’s mate aboard HMS Rattlesnake on a voyage of exploration and discovery to Australia. His observations and writings drew him closer to the science of “development theory,” as the Charles Darwin thesis of “evolution” was originally known. During his work and travels in Sydney, Australia, he met an English émigrée Henrietta Anne Heathorn. However, the demands of his career and journey meant theirs was a long-distance relationship.

Eventually, convinced by the writings of Darwin (“On the Origin of Species”) and his own research that humankind had evolved from other species, Huxley joined his contemporary in celebrated debates that challenged the pro-creationist theories of the late 19th century. Journalists and the public of the day nicknamed Huxley, “Darwin’s bulldog.” In an extraordinary exchange between Huxley and Samuel Wilberforce, bishop with the Church of England, in June 1860, the religious leader slammed the known “agnostic;” (Huxley had actually coined the term).

“[Are you] descended from an ape on your mother’s side or your father’s side,” Wilberforce jibed.

“[I] would rather be descended from an ape,” Huxley retorted, “than a man who misused his great talents to suppress debate.”

Eventually, Huxley caught up with his lady love from Australia and they were married in Britain in 1855. They had five daughters and three sons. I don’t know how much of the historic T. H. Huxley’s life our children expect of their contemporary Huxley. That’s up to them.

These days, most modern couples tend to flip through books or surf the internet to come up with a newborn’s name. A study from a U.S. website indicates more than half of parents today find it easier to name a girl than a boy. Parents deciding a girl’s name want the name to reflect individuality and femininity, while those deciding a boy’s name think it should convey strength. I know when we considered names for our daughters we flipped through books, soul searched for names in our own parents’ past and even made lists on paper before deciding.

I think it’s refreshing that Huxley’s parents have considered their own experience and a strong dash of history before bestowing a name on their son. As for his grandmother and grandfather, we’re just glad he’s here and that the paparazzi have kept their distance from the new prince in our lives.