The conversation began much the way many of my chats with men of a certain age do. I got his birth date. The man told me he was born in January 1923. He quickly pointed out he’ll be 91 in the New Year.

Next, I asked about where he’d grown up and because he’d lived through the Second World War, where he’d served. He explained he’d been with the East Yorkshire Regiment on D-Day as part of the Operation Overlord invasion force.

I asked Geoff Leeming if he would be our honorary veteran at the Uxbridge Oilies Remembrance Tournament on Nov. 9 at the arena.

“Fine,” he said, “but you know I didn’t serve in the Canadian Army. It was the British Army.”

“Doesn’t matter to me,” I said. “You’re a veteran in my books.”

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised at Leeming’s concern that I get the details right. It’s typical of a generation that, first, doesn’t want to take credit for something it didn’t actually accomplish, and, second, believes in getting the details of history as accurately as possible. The group Tom Brokaw called “the greatest generation,” saw the threat of Nazism in the 1930s, put civilian life on hold for six years, vanquished the European dictators, and then rebuilt most of what had been destroyed in the interim. Frankly, I don’t think the people liberated by Geoff and hundreds of thousands of his Allied comrades, stopped to look at the shoulder patches on their uniforms. Most oppressed populations of Europe were glad to be free.

What’s unfortunate, however, is that some of us in the generations that followed – in particular the one running things in some government offices these days – have betrayed the gift “the greatest generation” delivered to us.

This week I read in some of the federal Opposition literature that Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) plans to close down nine district offices… offices that provide consultation for vets in need, offices that include case workers trained to listen to veterans’ problems, offices in the remote countryside where former soldiers in Canada’s national army and reserve can feel most adrift. It means that when veterans of the recent 10-year-long Afghanistan war, now home in rural regions of Canada, can only get help via a 1-800 phone number because it’s five hours to the nearest open VAC office.

“Why (is) the Conservative government … turning (its) back on the veteran community?” Jim Karygiannis, Liberal critic of Veterans Affairs, said in the House of Commons this week.

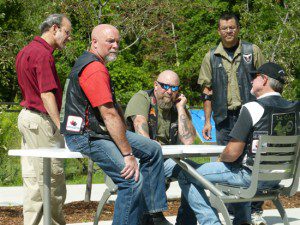

Back in July, I attended the 90th birthday party of Harry Watts, a Second World War dispatch rider who’d served with the 1st Canadian Infantry Division in Italy from 1943 to 1945. During the cutting of the cake, the speeches by local dignitaries and greetings from friends and family in the Kitchener area, another part of Harry Watt’s family arrived on the scene, the motorcycle-riding members of the Canadian Association of Veterans (CAV). Then the CAV bikers drifted off to a patio away from the crowd. Somehow I sensed – having completed their mission of paying tribute to veteran Watts – they went off by themselves to down a few bottles of beer and smoke cigarettes where they wouldn’t bother anybody.

“What makes you guys a cohesive group?” I asked them.

“Our service in Bosnia and Afghanistan for one thing,” one vet said, “and our hatred of the federal government for another.”

When I queried them about that hatred, they explained that the pension structure that Veterans Affairs uses today, versus what it was even a year ago, infuriates them. Apparently now, the federal government tries to buy out each vet with a one-time, lump-sum payment – say several hundred thousand dollars – which, when signed by the vet, absolves Veterans Affairs of any further service to that vet. This is the new regime at VAC – pay big now in return for no further dependence on VAC for the rest of the veteran’s life.

“Show me a vet returning from Afghanistan who wouldn’t jump at a lump-sum payment of a couple of thousand dollars,” one of the vets on the patio said. “I would.”

So whether it’s the department’s attempt to remove veterans from their long-term reliance on the federal budget, or the federal government’s appeasing fiscally conservative voters that they’re shrinking government and reducing costs with fewer VAC offices open, this country has clearly changed its view of veterans. In the last days before average citizens and vets acknowledge their comrades’ supreme sacrifice at the town cenotaph or the pay tribute to them Legion Remembrance Day banquets, the attention to detail that the veterans’ generation taught us to respect and honour, our leaders have decided – in the name of expediency and fiscal efficiency – is expendable.

And observing the difference between a Canadian veteran and any other, has suddenly taken on negative significance. Our country’s administrators have chosen to forget veterans on purpose at the annual time of Remembrance.

Nice to know canadian history be told correctly… My grandfather ( kenneth beaton ) wrote about ww2 … Wow ! Incredible stories. And he was quite the rebel. I have his memoirs locked up I have not even read them. I would love to see the movie the Great Canadian xscape that would be true an awesome.good luck with everything.