Stepping up to a music stand, last Saturday night, I realized it was the worst possible phrase to use. And it was the best possible phrase to use. I wanted to draw the audience in. I wanted to provoke it a bit too. I wondered how best to capture the essence of the evening. Then it hit me. I glanced down at my script on the music stand, and I finally blurted it out in one of my introductions.

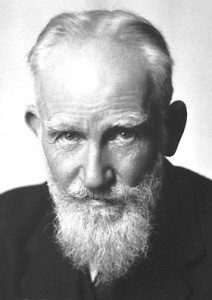

“You know that old George Bernard Shaw quote?” I asked. “It says, ‘Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.’”

The audible groan was entirely predictable. The St. Andrew’s Chalmers Presbyterian Church on Toronto Street was full of music-loving parents, music-practising youngsters and music-teaching instructors. It was the annual winter concert to raise funds for the Uxbridge Music Scholarship Trust, on this occasion featuring some of our community’s top-notch music teachers – including Rebecca and Tim Bastmeyer, Michelle Charlton, Carlie Laidlaw, Susan Luke, Jennifer Neveu-Cooke, Cynthia Nidd, Chris Saunders and Amy Peck. But this time they were performing, not professing. And the partisan audience didn’t like Shaw’s cryptic quotation one bit. Nor did I.

“Frankly, I think that’s hogwash,” I added. And then I went on to introduce Carlie Laidlaw, the lead singer with a group called Parental Discretion Band and another called Saunders Road. I continued by explaining that she’s the vocalist responsible for singing the national anthem at events around town and for recording a CD called “Hummingbird,” whose proceeds fund three hospitals around the GTA. I pointed out that Laidlaw provided warm-up for a concert headlining Murray McLauchlan. Finally, I reminded everyone, she also teaches music.

“Stick that in your pipe, G.B. Shaw, and smoke it,” I thought.

Then, I began to think about all the teachers in my life who’ve offered me those three vital dimensions of the teaching/learning equation. First, they knew what it was they needed to teach. Then, they understood how to explain it to others. Finally, they knew how to show others exactly the way it was done with the simplicity of kindergarten teacher, but with the expertise of a professor emeritus. Contrary to Mr. Shaw’s perception, teachers I’ve known could both teach and do.

Probably the earliest teacher in my life on those counts was the man who taught me both Grade 5 and Grade 7 at elementary school. Mike Malott couldn’t have been more than 10 years my senior, but he knew the pathways to hearts and minds of my classroom of 11-year-olds and then 13-year-olds better than anyone I’ve ever encountered. He inspired our fascination for history by showing us its characters. And on the sports playground, Malott imparted the skills of baseball and soccer by making us believe in each other as teammates and because we knew he could play any one of the positions around the field better than anyone in town. We knew he could show us as well as tell us anything the game had to offer.

At Ryerson, I experienced the brilliance of broadcast writer Christina MacBeth. She taught the craft of writing for advertisers, by showing us how they determined consumers’ needs. She delivered the basics of writing to time, by helping us see the language not just as bits of copy, but as split-seconds of a ticking clock. And she made us respect the vitality of English by forcing us not to write passively, but to construct images actively. I remember the day she came into a class, told us all our assignments were lame and boring, and then took away the best crutch we’d ever known – the passive verb “to be.”

“For the rest of the semester you cannot use any form of the verb ‘to be’ in any script assignment you hand in,” she said.

And we thought she was crazy. She was. Crazy like a fox. By the end of the semester, because MacBeth had forced us to employ words of action and impact, we were writing the best copy of our lives, all because she knew from doing it, how to teach it.

And I guess I need to thank my father – the greatest teacher of my life. I’ll never forget that day in elementary school, when, after typing my umpteenth essay to help me get a passing grade, he put his foot down.

“That’s the last one,” he said. “From now on you do the typing.”

By understanding I needed to learn by doing it myself, he forced me to sit at the practise pads. He showed me the concept of touch-typing. And he illustrated that axiom our entire family of writers has come to live by. “Nothing ever gets done,” he always said, “until the seat of the pants hits the seat of the chair.” Classic words from a man who knew how to teach, but even better, how to do.