Yesterday afternoon, in the town of Port Carling, Ontario, members of the Royal Canadian Legion, Branch 529, gathered and exchanged stories relating to the Second World War and the Great Escape. Among them, Philip Gunyon remembered, at age 7 in September 1939, that he and his mother had survived the U-Boat torpedo attack against the S.S. Athenia the first British ship sunk by Nazi Germany in the war. And Jack Patterson, a veteran of the famed Algonquin Regiment from Central Ontario, recalled being captured during the Falaise campaign in July 1944, and ending up at Stalag VII-A near Munich.

Gord Kidder recalled his namesake, Gordon Kidder, the German scholar at Stalag Luft III and the roles he played familiarizing fellow kriegies with the idiosyncrasies of the German language.

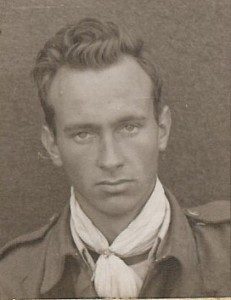

Among his accomplices in the instruction was fellow-kriegie Frank Sorensen. Following his capture during the 1943 North African campaign, in letters home, P/O Sorensen wrote about his melancholy, but not with purpose.

“Although we are rationed to four cards and three letters, I think it extremely difficult to fill in a letter to you,” Sorensen wrote in May 1943. “The last letter I wrote to you from North Africa was a very short one… Dad, would you send me the Thesaurus, please?” And just two months later he again wrote, “Would like Thesaurus sent out.”

Examination of an average thesaurus, first published by English physician Peter Mark Roget in 1852, reveals that each dictionary of synonyms contains a section called “Foreign Phrases,” which translated common expressions of the street in such languages as French and German.

And since German Luftwaffe guards at the North Compound encouraged their imprisoned enemy officers to spend their leisure time listening to music, watching theatre or reading in the library, the arrival of numerous volumes of Roget’s Thesaurus among the POWs’ packages from home seemed completely innocent.

In the hands of scholar Gordon Kidder, his nephew Gord Kidder reinforced yesterday, the thesaurus wasn’t so much a celebration of German culture, but tangible preparation. When the designated escapers of the planned breakout reached railways stations, border crossings or seaports, it was hoped they could rely on Kidder’s “Foreign Phrases” classes to help get them through.