By Dave Johnson (Erie Media)

On the night of March 24, 1944, 80 Commonwealth airmen crawled through a 400-foot long tunnel, escaping Stalag Luft III, a POW camp near Sagan, Poland.

Of those 80 men, including Canadians, British, Poles, Greeks, Australians and others, only three — two Norwegians and a Dutch pilot — successfully escaped.

The remaining 77 were caught by the Germans, and of those, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo on the orders of Adolf Hitler.

The Great Escape, as it was known, was considered the greatest prison breakout in the history of the Second World War.

And, despite what the Hollywood movie of the same name would have everyone believe, it was not planned and carried out by Americans. No one escaped by motorcycle or plane and the 50 murdered men were not all shot at the same time.

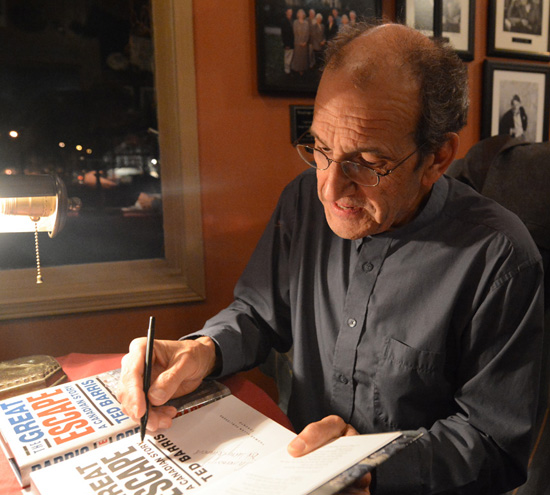

“Hollywood never let facts get in the way of telling a good story,” Canadian author Ted Barris told a packed house at Readings at Roselawn Thursday evening.

Barris wrote The Great Escape: A Canadian Story, and told the real story of how Canadians were behind it all.

The Great Escape, the third most popular war film, has stars like Richard Attenborough as a British soldier who masterminds the whole plan, with Charles Bronson as a Polish trench-digging expert, James Garner as an American with a talent for theft, Donald Pleasence as a master forger, and Steve McQueen as an American rebel.

“Hollywood would have us believe the tunnel king was Charles Bronson … it was Wally Floody from Chatham, Ont., not a Polish RAF officer”

Barris said Floody worked gold and ore mines of northern Ontario, and it was there he learned his tunnelling skills.

The real scrounger in the escape from Stalag Luft III was Barry Davidson, of Calgary, who had offered to fly for Chinese General Chiang Kai-shek against the Japanese.

Davidson had learned to fly well before the Second World War.

Tony Pengelly, of Truro, Nova Scotia, Barris said, was the master forger in the operation, and flew all manner of planes when he was with the RAF.

Barris revealed a local connection to the Great Escape during his talk.

He said Gordon Kidder, of St. Catharines, who was one of the 50 officers murdered by the Germans, was instrumental in teaching other escapees German.

One day before his talk, Barris had been in Poland at the former POW camp with Kidder’s nephew.

“It was a moving time.”

He said the Great Escape was actually years in the making.

Many of those involved in the action had been in other POW camps and had made many unsuccessful escape attempts.

Several of the men, he said, were together in Stalag Luft I near Barth, Germany.

“Escape was a private enterprise then,” said Barris, adding there 47 tunnels dug at Stalag Luft I.

Stalag Luft III was the Luftwaffe’s main POW camp for those prisoners considered to be troublemakers, meaning those who had tried to escape from other camps.

With the German air force running the facility, it abided by the Geneva Convention, which meant officers didn’t have to work. All they had to do was show up for roll call.

Barris said it freed them up to plan the escape.

With the camp built in the middle of a pine forest on powdery white sand, the escapees had to find a way to dispose of the coarse yellow sand found 30 feet below ground where the tunnels were.

One element the Hollywood movie got right, the author said, was how soil was disposed of. Prisoners, called penguins, had bags of sand in their legs and dispersed it near a fire pool that had been dug in the ground and had the same coarse yellow sand.

The sand was later dumped underneath a theatre built on site. The theatre had a basement, and unlike every other building, a solid foundation.

Barris said the POW’s buildings were built on stilts so the Germans could watch and make sure no one was tunnelling below.

The prisoners, however, exploited the one weakness of the buildings – the chimneys, which were built of concrete and went into the ground. They went through that concrete and rebuilt a floor system so perfectly, the Germans never knew it had been broken through.

Barris said the POW’s had a system set up with stooges, basically lookouts, in the camp to alert the men tunnelling.

“They could close up a tunnel in 60 seconds if they had to,” he said.