One day last summer, Laurie Laychak came back to the place where her husband David died. She visits the recently inaugurated cantilevered benches, Crape Myrtle trees and light pools of the Pentagon Memorial several times a month. Yes, it’s a pilgrimage. But she’s also on a mission. This day, the Laychaks’ daughter Jennifer has joined Laurie for the drive over. Just before her mother meets a group of travel journalists from Canada, Jennifer makes a painful admission to her mom.

“I can’t remember Dad’s voice,” the 20-year-old said.

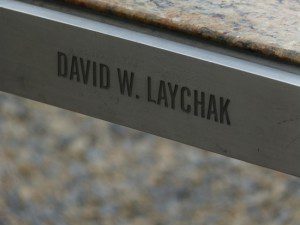

Minutes later, her mother leads the Canadian writers to one of the 184 memorial benches made of stainless steel and inlaid with granite. Before she begins her story, Laurie kisses the fingers of her left hand and touches the ledge engraved with her husband’s name “David W. Laychak.”

“I feel compelled to make sure visitors know these people were not numbers, but actual lives,” Laurie Laychak said. She’s now 52.

On Sept. 11, 2001, just after 9:30 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77, travelling at about 500 miles per hour, roared over a slight rise in Virginia’s iconic Arlington National Cemetery, clipped ground antennae, bounced off the ground near Washington Boulevard and ploughed into the first floor on the west side of America’s (then) 58-year-old defense department headquarters. The resulting explosion killed all 59 passengers and crew on the jetliner (as well as its hijackers) and 125 inside the Pentagon. Standing metres from the point of impact, Laurie Laychak gestures in the air to illustrate the five rings of offices within the Pentagon; the outer-most ring was where David worked that morning in his role as a civilian budget analyst for the U.S. Army.

“He was literally at ground zero, where the plane hit,” she said.

That Tuesday morning 13 years ago, Laurie Laychak worked as a substitute teacher at an elementary school where they lived in Manassas, Virginia. The school office contacted her to say there’d been an attack on the Pentagon. With all Washington-area phone systems jammed she couldn’t reach David by phone; she told their two children – Zachary nine and Jennifer seven – there’d been a fire where their father worked. On Wednesday she began calling area hospitals. On Thursday an impromptu support centre told David’s brother and sister, “if you haven’t heard from your loved ones by now, they’re gone.” Searching for the words to explain to her children Laurie admitted it was the lowest moment of her life.

“I cry over Hallmark cards and Disney movies,” she said. “Not in my wildest dreams would I have thought a plane would fly into the Pentagon.”

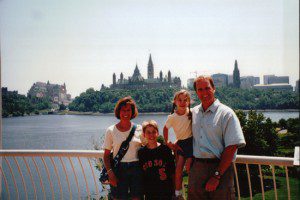

David Laychak and Laurie Miller met at the Pentagon in 1984. They’d both come from families with military backgrounds and according to the alumni magazine for Brown University (David’s alma mater) the two were among the youngest working in the office and fell in love. For Laurie, David’s blond hair and blue eyes were attractive enough, but so was his pickup truck; he’d purchased it because friends always needed help moving. “He just had a gentle soul,” she said. They moved to Arizona for a while, but in 2000 David was offered a promotion back at the Pentagon, and they returned to Virginia.

Weekends became family time. David was an American history buff anyway, but having so many historic locations so close by, gave the Laychak family ample time to explore battlefields and monuments together. On the road, David entertained his wife and children by singing “God Bless America.” There was a lot of teacher in David Laychak too; he’d played football at Brown and took to coaching Zachary’s basketball, baseball and soccer teams. “We were always hearing people request him as their coach,” Laurie said. “He was just so patient.”

Son Zachary had no patience with his father’s death. Just disbelief. Why would someone do this to his dad? How could someone as strong as his dad be gone? On the 10th anniversary of 9/11, he told American Forces Press (AFP) that on the night of Sept. 11, he’d gone for a sleepover at a neighbour’s house. He woke up at 6 a.m. on Sept. 12, saw his father’s parked car in the driveway and felt relief. He didn’t realize that a friend had driven his dad’s car home. Denial turned to anger. Zach wore a bracelet with his father’s name engraved on it and never took it off. He became a fan of America’s war against terror and even years later “felt pure joy” when Osama bin Laden was killed. Zachary has nearly completed a degree in political science and communications and is considering law school.

When the anniversary ceremonies came along, Laurie gave her children the option of attending. Both did initially. Laurie said her daughter Jennifer – seven at the time of David’s death – responded differently from Zach. At first she cried a lot and slept with her mom. Then she took to writing down her thoughts. “Mommy, you should write a journal,” she told her mom. “You can copy mine.” Today, Jennifer Laychak studies psychology and the neuro-sciences at university.

“To this day,” Laurie Laychak said, “it’s still hard for them both.”

Nor is the way through any simpler for their mom. Along her road to recovery she joined the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS) to help others coping with the post-traumatic stress disorder. She has remarried because she didn’t see herself playing the widow role “becoming an old lady in a black veil. How can I be a widow? I was 39,” when 9/11 happened. And despite the tears that inevitably recur, she makes herself available to take visitors to her husband’s memorial bench at least three hours a month.

Leading the visiting Canadian journalists through the Pentagon Memorial garden last summer, Laurie Laychak pointed to the fully repaired west wall of the U.S. defense department headquarters. A salvaged scorched-black stone at the base of what used to be her husband’s office area was the only visible evidence that 9/11 ever happened. Then, a jet taking off from nearby Reagan National Airport, roared overhead. Laurie flinched.

“This is my reality,” she said.

As powerful as the hijacked jet explosion into the first floor of the Pentagon was, some of the 28,000 military and civilian employees inside the 3-million-square-foot building neither heard nor felt a thing on 9/11. They just followed directions to evacuate the building. Even if those inside the Pentagon let the terror of what happened fade and even when that last blackened stone is weathered clean, Laurie Laychak promised she’ll be at the memorial telling David Laychak’s story.

Thanks for this article Ted , it’s an eye opener. People who have no real connection to tragic events can never understand how those who have been touched by tragedy feel. We can take a guess but that’s all it is .

This article is important to make people realize when the crowds thin and your on your own , the pain of loss is forever!