Early in the celebration of Bill Cole’s life, last Sunday afternoon at Wooden Sticks, his son Rob talked about the periodic disconnect that had existed between himself and his late father. Rob said he thought it was much the same as the disconnect between Bill and his father, First World War veteran Thomas Clark Cole. But Rob admitted a reality that many sons and daughters do.

“I was astonished,” Rob Cole said. “The older I got, the wiser Dad seemed to become.”

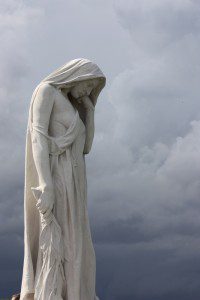

Indeed, I remember walking with Bill Cole, then 81, through the reconstructed Grange Tunnel below the Vimy Ridge memorial in 2007. Bill and Elinor Cole were travelling with us to Vimy for the 90th anniversary commemoration that spring. As we explored the place where 15,000 Canadian troops had waited underground to go over the top on the morning of April 9, 1917, Bill told me that his father Thomas had fought with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders) at Vimy. Bill said he’d never been able to get his father to talk much about the event, and had consequently never understood his father’s war.

“During the battle, my father was hit by machine-gun fire,” Bill recalled finally learning from his father Thomas. “And wounded, he walked five kilometres to the town of Arras before being given a field dressing.”

It was then, that Bill said he realized, as Mark Twain put it so glibly, that – with age – his father had suddenly shown great experience and wisdom.

My guess is that most children – the very famous and the not so famous – learn of their parents’ wisdom the same way. Whether George H. and George W. Bush or Pierre Elliott and Justin Trudeau, no doubt the political learning curve posed a gap that – with time and maturity – was eventually bridged. Whether Lionel and Nicole Richie or John Allan and Stuart Cameron, each generation learned that music could smooth relationships more readily than any other form of communication. In business dynasties – whether the automotive Fords, the oil refinery Irvings, the financier Rothschilds, the food marketing Westons, the realtor wizard Trumps or the broadcasting Rogers – one can bet that never was there familial unanimity across the balance sheets of their lives.

I’ve always been amused that the two American writing giants – father Irving Wallace and son David Wallechinsky – went by different surnames. It wasn’t a family tiff, but apparently a British customs officer who triggered the son’s name change.

“Ah, Wallace,” the officer said greeting David at the customs gate, “a good Scottish boy coming home.” And so David immediately decided to revert to his Jewish roots, changing his name to Wallechinsky.

I was always kind of upset that my grandmother had chosen to blend her family into the American melting pot by changing the original surname from Barbaretis to Barris. (There’s actually a loving cup in our front room with my father’s then name “Alex Barbaretis” inscribed on it.) And my father never seemed to care about the change. I always thought the original name had a lot of character. But, like most fathers and sons, he and I didn’t always see eye to eye.

As a kid, I remember being disciplined for some misdemeanor or another, and until I agreed to apologize face-to-face I was grounded. I proved just as stubborn as Dad in refusing to apologize, but I eventually realized his authority could outlast my principles. I apologized and we were best friends again. I think that’s the part about growing older and realizing each year, as I grew closer to fatherhood, my dad’s wisdom grew more and more apparent. On the other hand, my mother always seemed wise to begin with and she didn’t need any Mexican standoffs to make the point.

“Listen to yourself,” she used to say, “and you’ll hear what’s right and what’s wrong.”

The same European trip, during which the late Bill Cole told me about his father’s wounds at Vimy, a few days later found Bill and I walking over the chert-rock beach at Dieppe. This was, of course, the place where more than 900 Canadians had died in nine hours during the infamous raid against the French seaport in August 1942. As he had never understood the realities of his father’s generation, and in particular the Great War, so, Bill said, his son Rob never appeared to understand the Second World War that had happened during Bill’s youth.

“Then, Rob came for a visit,” Bill said. “Living in Paris at the time, Rob said he’d suddenly taken a side trip to pay homage to the dead of Dieppe. He brought some stones from Dieppe beach. He said they were a fitting tribute to the dead Canadians; when the stones were wet, he said, they turned blood red.”

I guess – given time – sons grow wiser in a father’s eyes, just as a father grows wiser in a son’s eyes.

I am upset about what Remembrance Day has become in Canada. It has become a celebration of war and militarism. The impression I get today is that it is no longer about how horrible wars are. Instead, its about how war can be wonderful character building experience for young. Furthermore, Remembrance Day, today, perpetuates the old lie that it a splendid thing to die in battle. And that death in battle is the highest form of glory a person can aspire to.