The concept was fairly simple. Oscar-winning moviemaker Chris Landreth leads his audience into the recesses of the brain of a character named Charles Langford, who’s attempting to remember the name of a long-ago friend he’s suddenly re-encountered at a party. You know… It’s when you see the face, but you can’t remember the name… Well, Landreth used that premise in an 11-minute short film, called “Subconscious Password,” which we recently saw during the annual Short Film Festival at Uxbridge’s Roxy Theatres. The film becomes a madcap edition of that classic TV game show “Password,” with every contestant knowing that the long-ago friend’s name is “John,” except our hero.

The concept was fairly simple. Oscar-winning moviemaker Chris Landreth leads his audience into the recesses of the brain of a character named Charles Langford, who’s attempting to remember the name of a long-ago friend he’s suddenly re-encountered at a party. You know… It’s when you see the face, but you can’t remember the name… Well, Landreth used that premise in an 11-minute short film, called “Subconscious Password,” which we recently saw during the annual Short Film Festival at Uxbridge’s Roxy Theatres. The film becomes a madcap edition of that classic TV game show “Password,” with every contestant knowing that the long-ago friend’s name is “John,” except our hero.

“Landreth’s spellbinding animation makes anomic aphasia unforgettably entertaining,” explained the Roxy program.

I loved the movie short. But what made this surreal adventure into the deepest corners of Langford’s brain so memorable, I thought on reflection, wasn’t so much the visuals; although some of the effects reminded me of the re-entry scenes from Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

No. What made the travels of our hero from one failed Password round to the next so unique, were the realistic sound effects. Brain storms were the equivalent of atomic explosions. Time travel tore our ears off. And the voices of each new contestant – his mom, Sammy Davis Jr., his babysitter when he was four, and even James Joyce – despite being animated, seemed dead-on real.

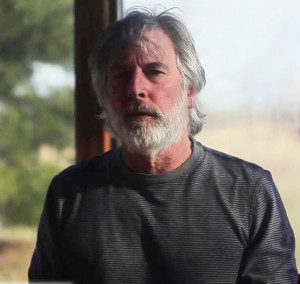

Remarkably, I learned that many of the unique sounds created for Subconscious Password came from the years of experience and studio facilities of an extraordinary Foley artist in our midst – Andy Malcolm – who joined us at the Roxy that evening. Foley, named after 20th century sound technician Jack Foley, is sound production that happens after the film is finished, when sound effects are performed in sync with the edited film. Andy Malcolm’s been doing it professionally for 40 years. Bearded and unassuming, Malcolm shrugged off the genius of his work (and his mantel of Emmy, Genie and Gemini Awards it’s brought him at Footsteps Post-Production Sound Inc.)

“There’s nothing magical about it,” he said. “It’s just sound.”

I spend each fall semester at Centennial College teaching broadcasting and film students why real sound – in radio, movies and television – is so vital. I know it’s obvious. But if you’ve shot the visual of an animal in the jungle, or a battle scene in the middle of a war, or I guess the cast of characters on the set of a 1960s TV quiz show “Password,” it helps if each sounds the way it should. And, as I try to impress upon my students, that’s the way it was done in the golden days of radio, back in the 1930s and ’40s.

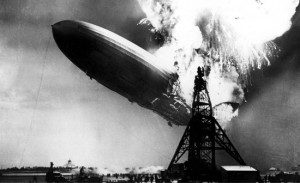

As an example, I show them the way Herb Morrison’s simple on-location WLS broadcast of the apparently uneventful arrival of the German zeppelin “Hindenburg” at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937, suddenly became an historic live account of an air disaster.

“It’s smoke and it’s flames now… and the frame is crashing to the ground… Oh, the humanity,” Morrison wept into his live mike as the airship burned and crumpled to the ground, killing 36 people.

Mind you, back in the 1930s and ’40s it was much easier to walk out your door, set up a microphone and recorder and get the pure sound you needed. But supposing you couldn’t get the actual sound and had to approximate it? Well, that’s when the recreation or Foley production of a Jack Foley or later an Andy Malcolm comes in handy. For example, I mention animals in the jungle; back in 1933 when RKO was about to release the original “King Kong” movie. Among the final elements to make Kong believable was his gorilla-like roar; Foley artists actually created by playing backwards the sound of a lion recorded at the San Diego zoo.

I also mention war sounds. I remember when I assembled research on D-Day, I came across the famous film footage of Canadian troops landing on Juno Beach on June 6, 1944. Through Chuck Ross, a member of the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit during the Second World War, I learned that the 35mm silent film had been shot by cinematographer Bill Grant. In turn, before the film appeared in movie theatres in the U.K., the U.S. and Canada, I discovered that a Canadian film technician named Ken Ewart, in London, England, had edited and mixed sound effects of gunfire into the famous footage.

“One of the reasons I got the editing job,” Ewart told me, “was that I knew what all these weapons sounded like.”

When the Short Film Festival screening of Subconscious Password was over, the other night at the Roxy, I suggested to Andy Malcolm that what he was really doing as a Foley artist was “sweetening” the film’s soundtrack.

“No,” Andy said. “We’re just making the sound, sound real.”

That’s because hearing is believing.