My writing staff and I had just completed a production meeting. I had just given our writers – the senior students of our online newspaper at Centennial College – their Remembrance Day assignments. With the recent loss of two reserve soldiers here in Canada, we were all sharply focused on Nov. 11 coming next week. So, I’d gone around the table and assigned stories to our student reporters. One would write about a woman in the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War. Another had an interview with an Afghanistan vet. A third would feature young military cadets.

My writing staff and I had just completed a production meeting. I had just given our writers – the senior students of our online newspaper at Centennial College – their Remembrance Day assignments. With the recent loss of two reserve soldiers here in Canada, we were all sharply focused on Nov. 11 coming next week. So, I’d gone around the table and assigned stories to our student reporters. One would write about a woman in the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War. Another had an interview with an Afghanistan vet. A third would feature young military cadets.

And one reporter, a young man named Jasun, needed a phone number for a D-Day vet I asked him to interview.

“May I give you a bit of background?” I asked him.

He started writing notes on a single sheet of paper with his other hand as the writing surface.

I invited Jasun into my office. He sat at my desk. I stood across from him and gave him as much detail as I could about the 90-year-old veteran he would be interviewing later that day or the next.

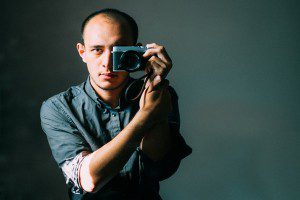

The 21-year-old University of Toronto journalism student dutifully wrote down every historical point I offered. He noted possible questions to ask. I made a note of how thoroughly he seemed to reorganize the information I’d offered, sensing that he could do the interview with ease. One of his classmates, who’d told me Jasun didn’t like doing interviews, later said Jasun felt this would be a relatively easy Q and A. As Jasun and I wrapped up our one-on-one chat, I knew I didn’t have to remind him to take his camera. He has been the best portrait photographer on the student staff. Last summer, he assembled written and photo portraits for a magazine story about lesbian and gay youth in Toronto.

“LGBTQ people suffer the same fate that any marginalized groups do,” he’d written introducing the feature. “The goal of this project is to represent the diversity of young LGBTQ … on their own terms.”

With the details of his D-Day veteran interview seemingly in hand, I asked Jasun if he needed anything else. A young man of few words in just about every situation I could recall, he shook his head, sort of smiled and went on his way. I then called the veteran in question to let him know the young reporter would soon be in touch. I had no idea the veteran would never meet Jasun. His fellow students would never see him again. And I would learn, within an hour or two of that meeting in my office, that Jasun had taken his own life.

“On their own terms…” The phrase kept ringing in my head. When it became clear that the initial police reports of his suicide were accurate, somehow that phrase Jasun had used in the magazine article captured every aspect of that tragic day. It summed up much of the young man’s attitude to work and life. It aptly described the way Jasun had come to his decision. And it seemed to capture the way we would all have to face the emptiness we felt after he was gone. None faced an emptier aftermath than Jasun’s parents and sister, whom I visited later that night.

We sat in the kitchen of their modest Scarborough home into the evening trying to explain what had happened. As calmly as they appeared to be at accepting the end result, they couldn’t connect his recent behaviour around their home with the act of committing suicide.

They considered his seemingly stable family environment, his strong scholastic achievement to date and his past coping skills. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary until that evening when the family recalled that Jasun had reserved a book on suicide from the library, perhaps as legitimate journalistic research. But then after Jasun’s death they said they had also discovered suicide literature in the search history of his computer.

Like everything else in this young man’s life, he’d chosen to do this on his own terms. The next day when college counsellors gathered us to offer support, it became clear that Jasun had done everything to the beat of his own drum. He’d hung out at the gym to consider body-building because he was curious. He’d worked in the photo lab at a discount store, using his keen photographic eye to help pay his bills. He’d photographed everything from forests to political candidates to the felines at a cat rescue centre to make the world a better place.

“We’ve only gotten to know him in death,” one of his classmates commented.

Indeed, in that one meeting in my office, just hours before he chose to end his life, I felt I’d come to know his quiet ability better than at any other time in our teacher-student relationship.

And it will haunt me for a long time that I couldn’t help him do things on his own terms, and still survive.