Last Saturday night, during the “Coach’s Corner” segment on CBC TV, Don Cherry could barely contain himself. His partner on the Hockey Night in Canada segment Ron McLean asked the one-time coach of the Boston Bruins what he thought of a the hip check delivered by Minnesota Wild defenceman Keith Ballard on Anaheim Ducks’ star winger Corey Perry, earlier in the week. Cherry blurted out that it was perfectly normal, just “a hockey hit.” Seconds later, the HNIC producers showed one of Perry’s teammates dropping the gloves, challenging Ballard to a fight. Why?

“Somebody has to go after (Ballard) and answer the bell,” Cherry bellowed. “And if you don’t understand that, there’s no sense me talking about it!”

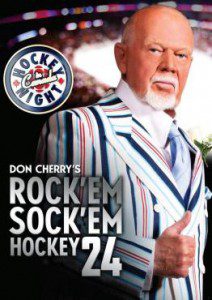

Don Cherry continues to categorize this brand of hit and retaliate hockey as just another basic and long-standing core principle associated with the professional game. He’s made a career (not to mention a pretty healthy cassette/DVD business) of characterizing the get-even hits, the brawling at centre ice and the sucker punching of notoriously non-pugilistic hockey players as some sort of code of honour.

For him and (I’m sorry to say) a sizable constituency of hockey fans, including an otherwise knowledgeable and articulate Ron McLean, retaliation in Canada’s national winter sport is as basic to the game as the wrist shot, skating backwards and a seventh game in the Stanley Cup Final.

For him and (I’m sorry to say) a sizable constituency of hockey fans, including an otherwise knowledgeable and articulate Ron McLean, retaliation in Canada’s national winter sport is as basic to the game as the wrist shot, skating backwards and a seventh game in the Stanley Cup Final.

My problem with his attitude isn’t so much that Cherry rants and raves about it all the time. Nor that he makes a lot of money on the side with his Rock’em Sock’em videos. I just dislike his Newtonian notion that the best way to deal with aggression is to use aggression right back. In spite of (or perhaps because of) my study of war and peace, I’ve never believed in that philosophy.

Fisticuffs, or even worse open warfare, has never seemed sensible to me. From as far back as my own parents’ strongly pacifistic view, if I felt anger rising in my head and heart, they always advised me that I should recognize it, acknowledge that it was irrational, and stop it in myself before I sparked more of it in the person with whom I was angry.

“Two wrongs don’t make a right,” they used to tell us in the playground.

And they were right. How many times have we witnessed that very principle illustrated to greater or lesser degree in a past century riddled with guerilla wars, civil wars and two World Wars? One need only look into the tribal hatreds that emerged from the former Yugoslavia, after the fall of the Soviet Union, or among the warlords of Somalia, Rwanda or even South Africa, to see the devastation that retaliation can bring. And one might argue that the 9/11 terrorist attacks and George W. Bush’s war on terrorism (incorrectly aimed at Iraq in search of weapons of mass destruction) are an even more catastrophic example of that playground moral run amuck.

I remember in that same childhood playground being bullied mercilessly by an older student who found great joy in poking fun at my name. I was too young and naive to realize the more his bullying got under my skin, the more he would bully me. When my mother finally got through to me, that I could beat him at his own game if I showed him his ribbing didn’t appear to affect me, the bullying ended. So did my urge to fight back physically, which would have been even more devastating, believe me.

At the township arena last week, my oldtimers hockey team faced our cross-town rivals. We play them once a month during their regular timeslot at the arena. Generally, each team wins its share of games… unless one or the other oldtimers team decides to invite younger (younger than the majority of us in our 50s and 60s) players into the game. When that happens, whichever side does it, the game inevitably becomes lopsided.

That was the case during our most recent match; our opposition brought out a couple of younger players to help bolster its lineup. Naturally, with the younger legs, they dominated the play. The game didn’t feel as fun as it usually has uring those once-a-month scrimmages. And after the game, in our dressing room, there was the good-natured grousing over our loss. But it still left a bad taste in our mouths. A few days later, one of my teammates suggested by email maybe we should invite some of our equally quick young offspring to play for our side during the next game a month from now.

“That’s called escalation,” I suggested to my teammates. While it might feel good temporarily to make up for our loss-of-face last game, in the end, I wondered what “answering the bell” would ever prove. In hockey and in life, there’s none of Don Cherry’s so-called honour in winning by whatever means, just to get even.