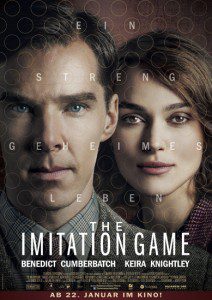

Seventy years ago, Europeans sensed the end of the Second World War was near. VE Day arrived May 8, 1945. A generation later, historians and moviemakers are still discovering how Victory in Europe was achieved. At Bletchley Park, an estate just two hours from London, England, details of the Allied intelligence victory continue to emerge. Last year, the movie The Imitation Game depicted the secret world of Enigma, Alan Turing and war work at Bletchley.

Seventy years ago, Europeans sensed the end of the Second World War was near. VE Day arrived May 8, 1945. A generation later, historians and moviemakers are still discovering how Victory in Europe was achieved. At Bletchley Park, an estate just two hours from London, England, details of the Allied intelligence victory continue to emerge. Last year, the movie The Imitation Game depicted the secret world of Enigma, Alan Turing and war work at Bletchley.

In the March 2015 edition of Zoomer magazine, read Ted Barris’s account of the Canadian angle on the code-breakers who hastened victory.

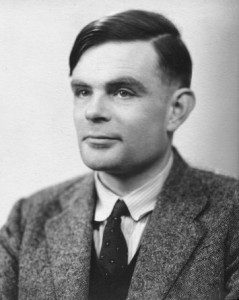

Canadian Nan Wright remembered the night the Allied war effort nearly lost its most valuable counter-intelligence thinker, Alan Turing, recently portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch in the movie The Imitation Game. And the mishap wasn’t because Turing, the brilliant mathematician who secretly broke Germany’s Enigma codes at Bletchley Park, fell victim to a covert plot. There was, however, a fall involved.

“Workers were building cement (buildings) we were about to move into,” Nan Wright (née Adair) said. “They had (dug) these great big ditches with electrical wiring in them. … It was the night shift and this girl came in and said, ‘An animal has just dropped into the ditch outside.’”

Nan and her fellow code-breakers cautiously emerged from Hut 8 at Bletchley Park, that night, peered into the darkness and giggled.

“Of all people, Professor Turing had fallen into the ditch. He was trying to clamber out of the trench. He really was, bless his heart, a very eccentric gentleman.”

In the mid-1930s, as a fellow at Cambridge University, Alan Turing had written a paper on computable numbers and plans for a computing machine. After receiving his PhD at Princeton University in New Jersey, at the outbreak of war in 1939, Turing took a position with the British Government Code & Cypher School (GCCS) at Bletchley, developing the bombe, an electro-mechanical device designed to help decipher German Enigma encrypted signals.

At the beginning of the Second World War, just 90 people from the Foreign Office moved into Bletchley Park, or “BP” as it became known. As the war escalated and Turing’s bombe began breaking thousands of encrypted German messages a day, the population at BP (by June 1941 part of Ultra, Britain’s top-secret signals intelligence branch) grew to nearly 10,000 people – a third of them civilians and three-quarters of them women.

“Our job was to break the German naval codes and keep the Atlantic safe from the U-boats,” Nan Wright told me in a 2006 interview. “I remember in January 1941, we lost 106 ships – not only the men, but all those goods.”

Born in England, but raised in southwestern Ontario, Nan (and her family) emigrated back to Britain just as the war began. At the time Nan’s father, an ex-military man, chafed at the idea that his daughter didn’t sign up for war service immediately. Then 19 and living with her family in the village of Leighton Buzzard, north of London, Nan tried to enlist in the Women’s Royal Naval Service. But the day she was supposed to meet the WREN recruiter in London, the Germans bombed the railway line into the city.

Not long after, she met a Royal Air Force officer working at Bletchley Park. He suggested she might consider joining volunteers at the complex, just nine miles from her home. Even on the day she arrived at the headquarters of the GCCS and met its head of code-breaking operations, Sir Hugh Alexander, Nan had no idea what went on there.

“We understand you would like to join us here,” Alexander said. “We call people here ‘the family.’”

“What will I have to do?” Nan asked. “I’ve never been to university.”

“That’s quite alright,” he said and handed her a copy of the Official Secrets Act to sign. “Would you like a little time to think about it?”

“That would be very nice.”

Alexander got up to leave the room and said, “How about five minutes?”

She signed immediately and started work in a drafty and cramped wooden building, known as Hut 8. She soon learned it was the home of the German naval decoding unit at Bletchley. Each day a civilian station wagon picked up Nan at her home; all she was allowed to say to her frustrated father was that she was “doing office work, but he knew I couldn’t type.”

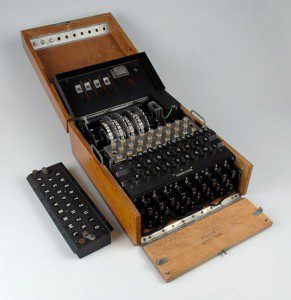

For eight shillings and six pence a week, six days a week for the next five years, Nan Adair moved into the inner circle of cryptanalysts working daily to break intercepted German codes on one of several Enigma encrypting machines secretly captured by Allied intelligence.

In Hut 8, during eight-hour shifts, Nan monitored German U-boat messages. The interception work was code-named “Shark.” She and her fellow cryptographers “got the crypts [through German] weather messages [which] were short. … We were taught the German words to look for in weather … often numbers and bits of messages,” she said. Those fragments were fed into Turing’s bombe in Hut 11 and when the bombe detected a pattern, it was fed into Enigma and the code was broken.

At Bletchley, Nan worked with cryptographers Hugh Alexander, Rolf Noskwith, Shaun Wylie, Joan Clarke and occasionally Alan Turing. In the chill of those long nights, when the cryptographers were allowed a break, they warmed themselves with a hot chocolate drink that Nan’s friends had sent from Canada.

“They used to come and bring their mugs,” Nan Wright said. “But Turing was so frightened somebody was going to steal his mug, that he put a chain on it and locked it to a radiator…the brains of Ultra locking his mug to a radiator.”

Madge Trull (who immigrated to Canada after the war) was also assigned to breaking Enigma codes sent to Kriegsmarine, the German Navy. Living in Bournemouth, England, at the beginning of the war, Madge (née Janes) followed her two brothers and a sister into the services. A series of psychological tests, taken when she joined the WRENS, determined that Madge had an aptitude for intelligence work. It was 1943. Plans for the Allied invasion of Sicily, Italy and eventually Normandy occupied the minds of Allied war strategists. Meanwhile, Madge and her fellow WRENS worked in decoding rooms, cracking codes to protect Allied military operations.

“We were given a (list of codes) brought out of Germany,” she said in 2006. “We fed the information into big machines – called bombes – with all these drums and thousands of little wires on it, each drum breaking the codes. … You’d turn it on, set it and wait.”

The Germans’ encoding machine, Enigma, could encrypt (translate) a message into code in over 15 million billion ways. They changed the encryptions every week, sometimes every day. The job of the drums and wires on the bombe units was to eliminate the majority of improbable codes and spit out the probable ones. Each hut at Bletchley housed five bombe units each with 70 to 80 WRENS working around the clock feeding codes into every bombe. Madge remembered her superior officers breathing down their necks, reminding the WRENS if codes weren’t broken, lives would be lost.

“When the bombe drums suddenly stopped, we went into hysterics. We were beside ourselves,” Madge Trull said. “The (German) code had been broken.”

Leading up to D-Day the bombes averaged 35,000 hours of operation per week, decoding up to 5,000 intercepted German messages each day. With that knowledge, British intelligence helped convince the Germans that D-Day operations would occur at Calais, not Normandy. Wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill paid tribute to the Bletchley Park staff by ensuring their efforts were underwritten by the war office from 1941 on, and by describing the female staff as “the geese who laid the golden egg and never cackled.”

One time Bletchley “goose” Nan Adair returned to Canada after the war and retired near Victoria, B.C. She died in 2007 never having ever told any member of her family that she’d served as a code-breaker throughout the war. Madge Janes married RCAF fighter pilot John Trull during the war and immigrated to Canada as a war bride, living today in Mississauga, Ont. Throughout my interviews with them, neither Nan nor Madge felt comfortable divulging memories of Bletchley, much less what they did. Not because it was painful, but because they sensed it was still against the rules. Nan’s father died before she was ever able to tell him about the vital war work she’d done.

“When we signed the Official Secrets Act, we were pledged to secrecy for 90 years,” Madge Trull added. “We haven’t made it that far yet.”