For some of us, Sunday morning holds a ritual that’s nearly religious. I’m talking about my oldtimers’ hockey league. But what with people away on holidays and a flu bug going around, attendance last Sunday wasn’t what it should be. One of my teammates arrived just before the first game, at 7 a.m., and was surprised how few of us were there.

“There were hardly any cars in the parking lot when I came in,” he said. “It’s as if it was Daylight Saving and everybody forgot to reset their clocks.”

As soon as he said it, I did a double take thinking it might well have been the weekend all the clocks go forward in the spring. But then I realized it was this weekend, on Sunday, March 8, the clocks “spring forward.” And that got my curiosity up and I wondered about the origin of Daylight Saving Time (DST), who’d come up with the idea, how the inventor convinced just about everybody much of the world to abide by it, where it’s practised and whether it works. I had a feeling Canadians were involved, but that remained to be discovered.

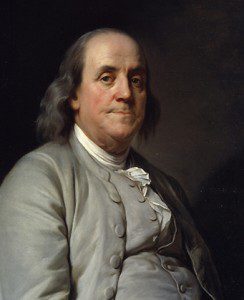

Benjamin Franklin, I discovered, is often credited with the idea of DST, but that’s not entirely true. In fact, in 1784, when he was 78 years old, the American politician was visiting Paris; he found his sleeping habits disrupted by early morning sunshine. He wrote an essay entitled “An Economical Project for Diminishing the Cost of Light,” in which he satirically suggested if Parisians simply woke up at dawn, they could save money with natural light.

“The economy of using sunshine instead of candles,” he called it, but all he really meant was that people should change their sleeping habits, not the hour on their clocks.

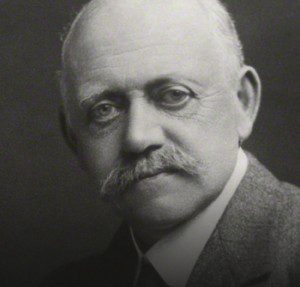

In 1907, William Willett, a British builder and avid horse enthusiast was just outside London one early morning outside London. He lamented that so few Londoners could enjoy the sunrise he’d seen because they were all still asleep. He wrote a brochure entitled “The Waste of Daylight” which recommended that the clocks be advanced by 80 minutes in four incremental steps during April and then reversed the same way in September.

The idea became his life’s passion. And it was Willett who suggested by making better use of daylight, the nation could save money spent on fuel for light and heat. His campaign became more attractive during the First World War when the country needed to conserve coal. But Willett never lived to see DST implemented; he died of influenza in 1915. DST was first enacted in Germany in 1916 and within a couple of years in Britain and North America.

There’s another myth about DST I discovered from reading an essay by Christopher Klein. I’d always thought that European and North American agricultural communities had lobbied in favour of daylight saving so that they could take better advantage of daylight hours to bring higher yields from their crops. Klein points out that DST was actually very disruptive. National DST was actually repealed in 1919.

“Farmers had to wait an extra hour for dew to evaporate to harvest hay; hired hands worked less since they still left at the same time for dinner; and cows weren’t ready to be milked an hour earlier to meet shipping schedules,” Klein discovered.

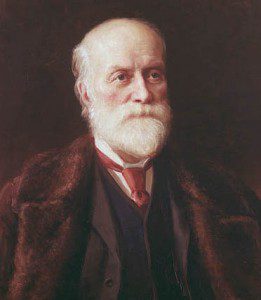

Oh, yes, the Canadian connection. Perhaps the only reason we have daylight saving time at all is because of the work of 19th century Canadian civil engineer, Sir Sandford Fleming. Upon his arrival in Canada from Scotland, Fleming joined the engineering staff of several different burgeoning railways firms. In 1871 he was appointed engineer of the rail line Canada wanted built between Montreal and the Pacific. As well as surveying where the CNR and the CPR would lay track, he advocated that cities adopt a standard or mean time according to time zones.

In 1884, at the Prime Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C., the world adopted his system of “cosmopolitan time” or “time reckoning.” We simply call it international standard time. And, of course, one can’t have Daylight Saving Time to change to, without Standard Time to change from. For that calculation and others Fleming was knighted in 1897.

Oh yes, for all my oldtimers’ hockey buddies, this Sunday is indeed the morning when clocks “spring forward,” which means the 7 a.m. game will really be taking place at what was 6 a.m. the day before. And the team reps won’t be very happy if you forget to turn your clocks ahead to be on the ice at the right time.

And by the way it’s Daylight Saving Time, not Daylight Savings Time. I guess the “s” got lost in the darkness one Sunday morning in March.