He felt compelled to act. He could not hold his tongue. He sensed that if he didn’t step in and say something, all the evils of the past might be repeated. That’s why during a neo-Nazi meeting in the Netherlands about 1960, Heiman de Leeuw demanded entry to the meeting as well as a voice to express his concern.

He felt compelled to act. He could not hold his tongue. He sensed that if he didn’t step in and say something, all the evils of the past might be repeated. That’s why during a neo-Nazi meeting in the Netherlands about 1960, Heiman de Leeuw demanded entry to the meeting as well as a voice to express his concern.

“You don’t deserve to be living in this country,” he told the supporters of fascism assembled in the hall. “I refuse to keep silent.”

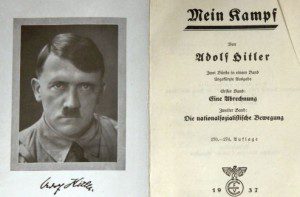

I learned this story from Heiman de Leeuw’s son Fred, this week, as Fred drove me back to Amsterdam after we had both attended the 70th anniversary parade through the streets of the city of Apeldoorn, commemorating the liberation of the Netherlands by Allied armed forces, principally Canadians in that part of the country, in 1945. In 1929, Fred’s father had read “Mein Kampf,” the autobiographical manifesto of Adolf Hitler, and predicted horrific events should Hitler come to power. In 1941, Heiman de Leeuw became one of thousands of “onderduikers,” people who went into hiding until the war was over. That experience ensured he would never allow himself to be marginalized or hunted again.

At that same Apeldoorn event, last Saturday, about 100 veterans and several thousand Dutch citizens gathered inside the city’s major velodrome to hear a military band concert as well as remembrances of Canadian soldiers’ wartime service and sacrifice in the long, last winter of the war. As part of the event, Sasha Kadiks, a 16-year-old Dutch high school student, recounted the pivotal moment in Apeldoorn’s liberation in April 1945.

“Canadian officers were under the impression that Apeldoorn was defended by 3,000 German soldiers,” she recited. “That’s why the Canadians planned a massive artillery attack on the city.”

I learned later that producers of the event had searched across the region for a student to recite this famous liberation story, written by Guus Essers. Because of her bilingual and public speaking skills, Sasha Kadiks earned the right to deliver the story about two Dutch resistance fighters risking their lives to reach the Canadians planning the final assault on Apeldoorn.

They told the Canadians the Germans had secretly withdrawn. An artillery bombardment would injure or kill innocent civilians. To check the claim, that night, 100 Canadian troops – all wearing socks over their boots to muffle their movement – followed the resistance fighters into the city. The Germans had indeed gone.

“An immense uproar followed,” Sasha concluded. “Tanks drove down Deventerstraat and grand columns of Canadian soldiers entered. … Apeldoorn was alive and vibrant again.”

More than 7,600 Canadians died in the campaign to liberate the Netherlands. Nearly a thousand of those Canadian lives were lost during the battle of the Scheldt estuary, the campaign to clear the route to the Belgian port of Antwerp in late 1944; they’re buried in plots at the Bergen op Zoom Canadian War Cemetery, a place that 76-year-old Geert Polak regularly visits. He told me he remembers exactly when he began this ritual of service to Canada’s war dead.

“I was 15 (in 1954) when I saw articles in the newspaper about the Canadians liberating our country,” Polak said. “I decided I’d better do something.”

He credits his teachers and parents for inspiring his regular visits to the Bergen op Zoom cemetery. He tends as many of the graves as he can. Just last week, he came to the cemetery to assist the family of fallen Canadian Pte. Albert Laubenstein bury his remains (found last year by a metal detector hobbyist scanning the area). Polak said, despite the rain, nearly 200 people from the town came to pay their respects. To local residents it’s as much a tradition as going to church or paying their taxes.

“(The Canadians) lost their lives here liberating our country,” Polak said, “and even though I continue to come here, it will never be enough.”

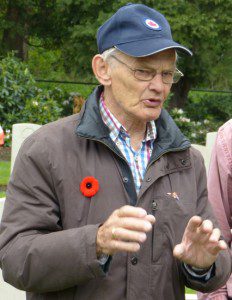

During my car ride with Fred de Leeuw back to Amsterdam last Saturday after the VE Day parade in Apeldoorn, he had told me his life story. The son of a Jewish “onderduiker,” Heiman de Leeuw who had hidden from the Nazis during the war, Fred, born in 1946, had tried his hand at an MBA, and even volunteered time on an Israeli kibbutz. Ultimately, he returned to Holland, became a businessman and now runs a cyber-security company. With the war seemingly so far away, I put a question to my volunteer chauffeur.

“Why did you drive all the way to Apeldoorn today, just to see that parade?” I asked.

Cognisant of his father’s experiences before and after the war and respecting the Canadians’ role in liberating his country, Fred de Leeuw said he’d joined a Royal Canadian Legion branch in Holland a few years ago. He explained that he and his fellow Dutch citizens don’t get the chance to say ‘thank you’ often enough. And guided by his father’s sense of doing the right thing, he added: “I guess I too refuse to be silent.”

It’s the way Dutch citizens continue to express duty in words and deeds.