It was getting late on Saturday afternoon. The chief dignitary at our event, the lieutenant governor of Ontario, had moved on to her next appointment. Most of the remaining dignitaries had left too. Only the volunteers were left cleaning up and chatting with us hangers-on. Suddenly a car pulled up and a couple emerged.

“Has the event already happened?” the woman asked. “Have they unveiled the sculpture?”

“The sculpture of Maud?” I repeated. “Yes, they have.”

“We’ve come a long way,” she said.

“Don’t worry. Just about everybody’s gone,” I said. “But the sculpture’s not going anywhere. She’s just waiting for you.”

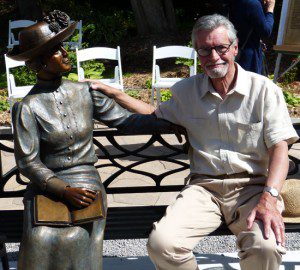

I led the woman and her husband past the front entrance to St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church and there she was – the newly unveiled Wynn Walters sculpture of Lucy Maud Montgomery seated on a bench. And with most of the volunteer hubbub now focused on cleaning up after the unveiling ceremony, indeed the couple did have Maud all to themselves. All I heard from the woman was a sigh of ecstasy as if her long drive from wherever was entirely worth it.

Most of the day, that churchyard garden in Leaskdale had been a hive of activity. Scores of volunteers had set up picnic chairs, canopies and tables full of bite-sized sandwiches, fresh fruit and glasses of rosé to toast the occasion. Politicians from the municipality, Queen’s Park and Ottawa had arrived to speak. Among the guests of honour, Lt. Gov. Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Kate Macdonald Butler, representing Maud’s heirs, Penny Smith, from the Ontario Trillium Foundation, Kathy Wasylenky, past president of the Lucy Maud Montgomery Society of Ontario, and of course Wynn Walters, who’d sculpted the life-sized bronze of Maud on her bench.

It all seemed so low key and local, though, as if Maud Montgomery, the wife of the local Rev. Ewan Macdonald, had simply invited a few close friends to a garden tea.

In fact, there was much more at play here. Though Maud’s early 20th century life in Leaskdale seemed to reach out only as far as the parishioners in her husband’s church or her children’s school mates in rural Ontario, in fact her writing, we have learned since, touched heart strings around the globe and a readership in the millions. To quote Jane Ledwell’s and Jean Mitchell’s work Anne Around the World, Maud’s book Anne of Green Gables (published in 1908) alone “became Canada’s first international best-seller and has now sold over 50 million copies.” Anne went on to be translated into 30 languages helping to “shape the identities of Montgomery’s readers around the world … and the fictional worlds of children.”

Online Web and print biographies attempt to quantify Maud’s worldwide reach. In addition to the millions of fans who followed Maud through her 20 novels (half of them composed while she lived in Leaskdale) among those celebrities who read her fiction were British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and Earl Grey, the Governor General of Canada. Arriving as a childhood refugee from Hong Kong in 1941, later Gov. Gen. Adrienne Clarkson claimed reading Montgomery helped her understand Canada. And no less than American author and humourist Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain) complimented Maud’s creativity.

“(Anne Shirley is) the dearest and most moving and delightful child since the immortal Alice,” he said.

The biographies go on to point out that Maud became the first woman in Canada to be named to the Royal Society of Arts in Britain, and was also invested in the Order of the British Empire. Speaking at the sculpture unveiling on Saturday, Kathy Wasylenky, past president of the LMMSO, explained that by the mid-1920s, Maud’s readership had expanded to Sweden, Holland, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Australia, France, Germany Israel, China, Japan, India, Spain, Russia and Poland. Kathy pointed out that in 1935 Maud was also elected to the Literary & Artistic Institute of France.

“There is not another Canadian author whose work is so universally enjoyed, nor so thoroughly researched and studied,” she said in an emotional tribute to Maud. “Her books have never gone out of print.”

Among those countries giving Maud’s writing a permanent home, we learned from another of the Saturday dignitaries, is Poland. Pickering-Scarborough East MP Corneliu Chisu, who has served in the Canadian Forces, talked about Montgomery’s extraordinary impact on his native country.

He explained that her 1926 novel, The Blue Castle, had become a musical in Cracow, Poland.

I didn’t stick around on Saturday afternoon to see or hear how the late-arriving couple enjoyed their viewing of Wynn Walters’ extraordinary Maud sculpture in the garden. Many at the unveiling said they’d put their smart-phone photos and impressions on Facebook. And that’s nice, but I think Maud’s international impact couldn’t be summed up any better than by MP Chisu.

“Polish soldiers carried her stories to the front lines during the Second World War,” he said. “Montgomery was a hero in Poland.”