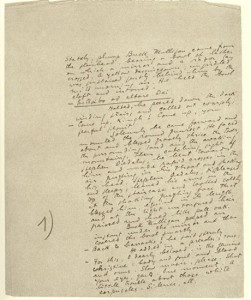

Did you know that the original manuscript for James Joyce’s book Ulysses rests in Philadelphia? That’s because a Philadelphian named Abraham Rosenbach felt he needed to acquire it. In 1924, when he saw the first version of the book, Joyce’s actual pencilled words on paper, Rosenbach bought it.

He paid $1,975 for it. At the time, he felt he was simply helping Joyce raise much needed cash. When Joyce’s fortunes changed and he tried to buy the manuscript back from Rosenbach, he refused. Later, Rosenbach offered to buy the page proofs for Ulysses.

Joyce was incensed, saying “when [Rosenbach] receives a reply from me, all the rosy brooks [a play on Rosenbach’s name] will have run dry.”

Over the weekend, I stood in front of the glass case where several pages of Joyce’s original manuscript lie on display. I was visiting Abraham Rosenbach’s long-time home on Delancey Place, one of Philadelphia’s historic downtown streets. I was drawn there, yes because the principal artifacts of the Rosenbach museum are books, but also to learn about the man who, according to some, was the greatest book collector in America.

While Joyce might not agree with the suggestion, Rosenbach was therefore one of America’s greatest supporters of literature – not only because he might ultimately be supporting writers with his purchases, but also because by preserving such rare books he was creating a museum of the finest first-edition volumes anywhere in the world.

In the Rosenbach collection I saw the first edition of Herman Melville’s famous book Moby Dick, originally called The Whale. I saw the original manuscript of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Underground, which Rosenbach purchased at auction in 1928 for $75,000. There’s the only surviving edition of Benjamin Franklin’s first Poor Richard Almanac, and Bram Stoker’s notes for Dracula, all sought out by a man who wished to create a private library of classics, but which later became one of America’s most vital public collections of rare books.

By coincidence, over the weekend, I met another Philadelphian bent on preserving American history of a different sort. Harry Helms lives in a retirement home, appropriately named Freedom Village. There, the 92-year-old veteran of the Second World War enjoys his neighbours, concerts, movies and conversation with many of the several hundred residents.

In addition, however, Helms serves as secretary-treasurer of the nearly three-quarter-century-old 94th Infantry Division Historical Society. He actually served in the famous military unit, sometimes known as “Patton’s Golden Nugget.” That’s because the 94th was drawn into the bloodiest battle U.S. troops experienced throughout the war – the Battle of the Bulge – from December 1944 to February 1945.

“I was one of the luckiest men in the 94th,” he told me on the weekend, “because before the fighting got bad, I broke my leg behind the lines and was evacuated to England.”

Nevertheless, Helms has guided to the post-war 94th historical society from a series of veterans reunions, to an attempt at establishing a museum at a military fort in Massachusetts, finally to the safe haven of a rare artifacts facility at the University of Georgia, just outside Atlanta. He gave me a copy of the society’s newsletter, which features a photo of Harry’s “G” Company in the 376th Infantry Regiment of the 94th Infantry Division. Seventy years after the fact, Harry Helms believes in keeping alive the stories and traditions of his wartime comrades.

“I don’t deserve the attention,” he said, “but those who fought through the toughest combat of the war do.”

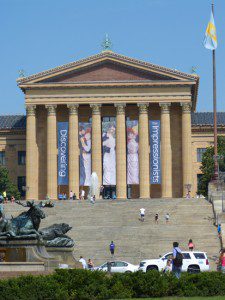

Meanwhile, it turns out that one of Philadelphia’s most iconic of locations, the Museum of Art (you know, where Sylvester Stallone runs up the stairs in the movie Rocky), currently exhibiting a show called “Discovering the Impressionists,” is paying tribute to another patron of sorts. The current exposition focuses on the professional acquisitions of French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel.

Why should one care about the name of a man who bought and sold art? Well, the exhibit goes to great pains to show that had Durand-Ruel not provided support to the painters who emerged in the late 19th century in the genre of impressionism, the world might never have known or admired the genius of Monet, Degas, Manet or Renoir.

Durand-Ruel took a chance on such artists and bought their works for the asking prices so that the struggling painters had the means to continue their unique exploration of the visual world. Late in his life, Durand-Ruel reflected, “at last the impressionist masters triumphed. My madness had been wisdom.”

Last Saturday, as my guide at the Rosenbach rare books museum completed her tour, I asked Cassie MacDonald (a poet) why she liked this job so much.

“When I walked in, it smelled like my grandma’s house,” she said.

When she applied as a docent (guide), she then had to complete a two-month training period in order speak with authority about the museum and Rosenbach.

“This place touches on a lot of life. It’s a privilege to work here.”

That says a lot about those who work to preserve heritage.