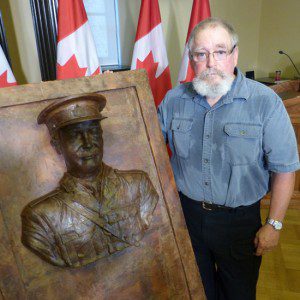

Sam helped Tyler make it through. But when he needed the same kind of assistance – nearly 100 years ago – there was no one there to help Sam through. Tyler Briley, from Port Perry, was in Ottawa last Thursday. The minister of veterans affairs was unveiling Briley’s latest creation, a wax sculpture of Sam Sharpe.

“It’s been a form of therapy,” he said. “I’ve just gotten well in the last year, in part, because of my work on this.”

For most of his adult life, Tyler Briley, now 60, has served in the GTA as a firefighter. He worked for 20 years on a heavy rescue truck responding to alarms for car crashes, apartment fires or to rescue kids who’d tumbled over the edge of the Scarborough bluffs. He said he transferred to the rescue brigade in his first year with the fire department because he wanted “a busier truck.” And that’s exactly what he got – busier and, as it turned out, more stressful.

“I loved every minute of it,” he insisted, “but I’ve seen things people shouldn’t have to see.” In fact, for a good portion of the years he served in the rescue unit, he was incapacitated. Because of the physical nature of the job, Briley sustained numerous injuries, including a severely damaged shoulder. But when he considers his 17 years of coping with the physical injuries, they pale next to the mental strain. “Looking back, I should have been treated for PTSD.”

That’s where the lives of modern day firefighter Tyler Briley and First World War infantry commander Sam Sharpe intersect. That’s how Sam helped Tyler through an illness they both had experienced. You see, in early 1918, after witnessing the slow but unstoppable decimation of his home-grown regiment, the 116th Ontario County Battalion, during the First World War, Lieutenant-Colonel Sharpe was pulled from the front line. Officials called it “shell shock.” But nobody knew how to treat it. Instead, Sharpe was shipped home. Then, in May (just months before the Great War ended), at a convalescent hospital in Montreal, the 45-year-old Sharpe died by suicide.

“It is my firm belief,” Minister Erin O’Toole said at the unveiling of Tyler Briley’s sculpture in memory of Sam Sharpe in Ottawa last Thursday, “that the horrors of war … left Sharpe a deeply injured man.”

The sculpture, actually a three-dimensional projection of Sharpe’s face and shoulders emerging from a flat surface, is not an epitaph to a soldier’s death in the Great War. No. For Tyler Briley, and perhaps even more for Minister O’Toole, it’s righting a wrong.

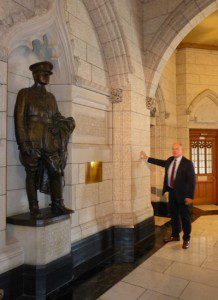

In his remarks prior to revealing the sculpture, the minister recalled arriving on Parliament Hill in 2012. In the foyer of the House of Commons, he said he spotted the bronze statue of former MP George Baker; it commemorated the dedication and sacrifice of what Parliamentary history books recorded as “the only Member of Parliament” to have died in the Great War.

“But we know that there were two Parliamentarians who died in the service of their country in the First World War,” O’Toole said, “George Baker and Sam Sharpe.”

Driven by this apparent oversight and spurred by his own service in the Canadian Armed Forces and those of comrades with PTSD (now recognized by the military, the government and society as a legitimate war injury), O’Toole launched a personal campaign. First, he wanted to ensure that LCol. Sharpe’s legacy became better known.

And second, he hoped by staging (with the help of fellow vet Romeo Dallaire) such events as the annual Sam Sharpe Mental Health Breakfast for Veterans, that Parliamentarians would address the stigma of mental health issues, particularly operational stress injuries in the military.

“You can be injured physically serving your country,” O’Toole said, “and you can be injured mentally serving your country.”

In the latest phase of his campaign to right the wrong of Ottawa’s Parliamentary records, the minister engaged sculptor Briley to fashion the face of LCol. Sharpe for the commemorative plaque. As a boy, Tyler said he took to sculpting his mother’s broom handles into totems. He advanced to soapstone (it reduced the number of gashes in his fingers). A few years ago, he prepared a bronze logo for General Motors and more recently a mounted Canadian cavalryman for the Canadian War Museum. Then came the call for the Sharpe relief.

“I did a lot of research on the man,” Briley said as he considered how to depict LCol. Sharpe. He chose to sculpt Sharpe as the battle-worn soldier he was just before he died. “I know what I’ve been through, but these [First World War soldiers] went through a hundred times worse than anything I ever experienced.”

“I did a lot of research on the man,” Briley said as he considered how to depict LCol. Sharpe. He chose to sculpt Sharpe as the battle-worn soldier he was just before he died. “I know what I’ve been through, but these [First World War soldiers] went through a hundred times worse than anything I ever experienced.”

So, at the ceremony to unveil the Sam Sharpe relief last Thursday, former firefighter Tyler Briley found artistic satisfaction and a feeling he’s on the road to recovery from his PTSD. LCol. Sam Sharpe may have to wait a bit longer. It’s taken 97 years for Parliament to officially recognize his PTSD. Healing the rest of the wound may require more time.

I may be a bit biased, but knowing the story of how this came to be and my dad’s history, this is a wonderful article. Thank you for taking the time to write it.

Hi Kasey… You ARE biased. You are entirely entitled to be biased. Your father’s passion to help right a historical wrong and his strength in overcoming his own inner demons are beautifully captured in his sculpture and his description of it to me. I thank you for taking the time to write a response to my column. I really appreciate it. Tell you dad, I’m proud of him too. Ted.