I have listened to it. I have read it. I have asked my friends – both women and men – what they think of it. And because I have a sister, a wife, two daughters and a granddaughter and many female friends of various ages, cultural origins, linguistic backgrounds and religious faiths, in my life, I have agonized over its message.

“Why would Canadians, contrary to our own values, embrace a practice … that is not transparent, that is not open and frankly is rooted in a culture that is anti-women?” Prime Minister Stephen Harper said in Parliament earlier this year, “That is unacceptable to Canadians, unacceptable to Canadian women.”

And I have reached the conclusion that these sentiments are vastly exaggerated, not representative of who we are as Canadians, nor a reflection of the way our citizenship system operates, very much rooted in a xenophobic attitudes, and perhaps worst of all, they are themselves anti-women, the very values that the prime minister claims to be defending. Not only that, but I also believe he fails to understand the plight and wishes of half the country’s citizens – women in Canada.

First let me offer some response to his attitude about the niqab that some women, who practise the Muslim faith, wear. I happen to teach a number of students whose cultural roots include a strong belief in Islam. Most of them tell me that no religious edicts, no men in their lives and no imams (Muslim clergy) dictate that they wear either a niqab or a hijab).

“We wear it because it’s an expression of personal preference and our connection to our culture,” one woman told me recently. And when I pursued the question, inquiring whether their faith demanded it, she said, “No. It’s a choice we make ourselves.”

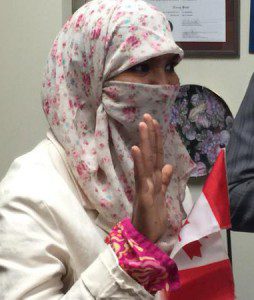

One might expect that the leader of a Conservative party would honour and defend an individual’s right to choice of lifestyle more than other parties. However, it doesn’t appear to be the case. Add to that, the prime minister was quoted in the same exchange about “a culture that is anti-women,” as saying that “we do not allow people to cover their faces during citizenship ceremonies.”

Not according to my sources. A veteran friend of mine, one who has a greater right to wrap himself in the Canadian flag than just about any politician I know, because he served his country in the Second World War, contradicts what Mr. Harper insists is the practice when landed immigrants become Canadian citizens.

Harry Watts, 92, a dispatch rider in the liberation of both Italy and Holland between 1943 and 1945, frequently officiates in citizenship court, congratulating new Canadians as they swear allegiance to their newfound country and sing its national anthem as citizens for the first time. Watts told me that his experience at such events is that women wearing veils must and do reveal their faces to a female adjudicator when signing the official papers. It’s only when those women attend the public ceremony that they feel compelled to keep their faces veiled. In other words, women with head dress are not flouting the rules. They’re abiding by them. And a head of government ought to know that.

But there are issues connected to the respect for Canadian women and the prime minister’s attitudes toward them that disturb me even more. I cannot understand why Prime Minister Harper appears to ignore the fear and anxiety that First Nations women in this country express over the disappearance and murder of so many in their community.

When organizations no less than the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Amnesty International have publicly called for investigations into the cases of no fewer than 1,200 aboriginal women murdered or missing in Canada, why wouldn’t the head of a law-and-order-focused government, jump at the chance to reinforce its political stance that criminals need to face harsher penalties? Why wouldn’t such a tough-on-crime administration relish the potential of appearing to support victims’ not perpetrators’ rights?

Despite such attitudes at the top, I am heartened by what I witness in my classroom, listening to the veterans I respect, and learning from my peers. My daughter, a teacher as I am, told me this week about a recent incident at her elementary school. She said that a friendly team game had just wrapped up in the schoolyard, where someone noted that the losing team “had more girls on it” than the winning one. Reacting to such a knee-jerk, sexist remark, the boys on the losing team, my daughter said, responded this way.

“That’s not a very fair comment,” the boys pointed out. “What do you think your mother would say to that kind of attitude?”

If only heads of state and chief legislators in this country had a better sense of the way their citizens view the rights and stature of women. It might be a more transparent and tolerant place.