The project seemed daunting. On paper, it looked as if I could pull it off. I was young. I had ambition. I had no sense of my limitations. And yet, the idea of actually travelling across the Prairies in search of eyewitnesses to help me document a piece of Canadian history, was just that – an idea and little more. It needed somebody, anybody to give it a vote of confidence. That’s when a couple of business associates offered me a lifeline. They knew I planned to begin my research in Winnipeg.

“Well, if you’re going to spend any time in Winnipeg,” brothers Jim and Hal Sorrenti told me, “you have to stay with Auntie Marg.”

“Who’s Auntie Marg?” I asked.

They explained she was their father’s sister, that she was a wonderful person and that of course she would take me in while I conducted my research at the Manitoba archives. That she had no idea who I was, nor how trustworthy, didn’t seem to matter. And to help seal the deal, the Sorrentis, both involved in a national car rental business, offered me a car for the trip from Ontario to the Prairies and back. The fact that I had only known the Sorrentis a few years seemed equally insignificant as far as they were concerned. I was to borrow one of their cars, travel to Winnipeg and stay with their Aunt Marg. No questions asked.

They explained she was their father’s sister, that she was a wonderful person and that of course she would take me in while I conducted my research at the Manitoba archives. That she had no idea who I was, nor how trustworthy, didn’t seem to matter. And to help seal the deal, the Sorrentis, both involved in a national car rental business, offered me a car for the trip from Ontario to the Prairies and back. The fact that I had only known the Sorrentis a few years seemed equally insignificant as far as they were concerned. I was to borrow one of their cars, travel to Winnipeg and stay with their Aunt Marg. No questions asked.

Well, the kindness of strangers doesn’t get much better.

More than 40 years later, the object of that research trip is a book about an odd part of Canadian history. This latest publication of mine – Fire Canoe – documents the little known role that paddlewheel river steamboats and lake steamers played in opening up the territory between what is now Winnipeg and the Rocky Mountains.

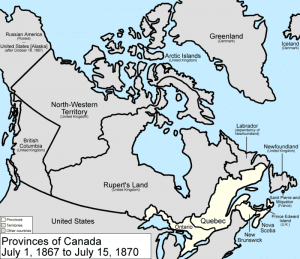

What’s more, at several key moments in Canada’s pre-Confederation era, I learned in my travels, those who ran the lake and riverboats in the territories west of the Great Lakes, more than any other factor, probably ensured that Canada became a nation from Atlantic to Pacific. They and their Mississippi-styled contraptions even preceded John A. Macdonald’s “national dream” (the Canadian Pacific Railway) and probably prevented Prince Rupert’s Land from becoming America’s northern most state. But that’s the content of my book, not how the unexpected gifts of so many helped me complete it.

“Auntie Marg,” as she told us to address her (because everybody did), accommodated me and Jayne (my fellow researcher and later my wife) for the better part of a week. She offered us a place to sleep and a base of operations for those I wished to interview. She rose each morning to have breakfast ready for us and had supper prepared for us when we straggled in after a full day of chasing interview sources or sitting in research rooms at the provincial archives then in the bowels of the Manitoba Legislature.

“I just want to help out,” she said as if she did it every day of the week.

As I say, Marg was just the beginning. Over the course of nearly three months on the road, Jayne and I made dozens and dozens more acquaintances. There was the man in northern Manitoba who allowed me to borrow his unique set of photographs of life on lake steamers. There was the curator of a small, local museum, who kept her doors open late to let us sift through its files. There were the couples who fed us more cookies and tea than we’d ever consumed in our lives. And, in particular, I recall a First Nations man who took me to the banks of the North Saskatchewan River and patiently explained how – as a young man in the 1920s – he had guided riverboats around shoals, snags and sandbars.

“Reading the river,” he called it. “It takes a lifetime to learn.”

There was one additional unexpected and potentially project-ending incident during that summer as we researched across the West. In the middle of the summer, in the middle of an intersection in Edmonton, in the middle of everything going so well, we were t-boned by another car. When our world stopped spinning, and we realized our seatbelts had saved us, there were papers, tape-recording equipment and camping gear strewn over the road. In an instant, however, there were bystanders making sure we were safe, contacting police and even opening their doors.

“If you need a place to stay,” one woman, a total stranger, offered, “you’re welcome to come to my house.”

And now I’m back in Winnipeg, to begin promoting this book. But the kindness continues. Instead of staying with Auntie Marg, as I did as a young, inexperienced writer 40 years ago, I’ve been invited by Marg’s daughter Doreen and her husband to be with them as I launch my tour across the Prairies. The full circle my work has travelled still benefits from unexpected gifts of generosity.