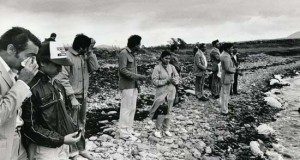

The first he knew of the story, came from a phone call early one Sunday morning in 1985. His producers at CBC told him to get on a passenger jet bound for Shannon Airport in Ireland and then to travel south along the Irish coast to where families from India were assembling.

Actually, they were scrambling to the coastline where they hoped they might find their relatives from Canada. CBC reporter Terry Milewski had been assigned to find these families and report on them.

“It was just a bizarre and horrifying situation,” Milewski wrote. “Most of the bodies (of their loved-ones) were never found. Most of the bodies went to the bottom of the sea still strapped in their seats.”

Milewski had been dispatched to cover the bombing of Air India Flight 182 (30 years ago last spring). And he offered his account of reporting on that story to Mark Bulgutch, a now retired CBC news producer for the latter’s book entitled “That’s Why I’m a Journalist.” The other night, I went to a public conversation in which Bulgutch chatted with CBC Radio producer Jeff Goodes about the book, its content – 44 prominent Canadian broadcast journalists offering insights about a momentous story in their careers – and the state of the profession.

Working as an editor and producer at CBC News since the 1970s, Bulgutch has the greatest respect for the people with whom he worked – camera operators, editors, anchors, producers, directors and studio crews – but he reserves his greatest praise for the reporters who got the stories.

“They are the essence, the lifeblood, the irreplaceable building blocks,” he wrote in his book.

Case in point, in Milewski’s coverage of the Air India story, he recounts the Indian families’ grace in the face of the tragedy, the ignorance of politicians (then prime minister Brian Mulroney called Rajiv Gandhi to express condolences for the loss of so many Indians, when the victims were mostly Canadians) and what Milewski calls the lies told by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the RCMP in their mismanagement of the investigation.

Perhaps most important, Milewski explained why he never let the story drop. “I would have felt that I was part of the problem if I had walked away without giving the families, the seamen who picked up the bodies, and the victims themselves a voice.”

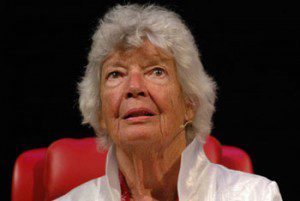

In my own experience, both as a student of her work and as a working colleague, I learned the extraordinary talent and skill of June Callwood, author of 30 books, more then 1,500 magazine articles, and even more newspaper columns. Like Milewski, Callwood believed strongly in advocacy journalism where and when it was needed. Thus, while a professional writer, she helped found the AIDS hospice Casey House, Nellie’s Hostel for Women and Jessie’s Centre for Teenagers, in Toronto. Her friend and former editor of Chatelaine Doris Anderson described Callwood in a Toronto Star obituary in 2007.

“Whenever anything happened, whenever there was a crisis, she just had to get in there,” Anderson said. “Most of us would have said somebody else should do something. Not June. There’s a very big heartbeat there.”

I could never claim the kinds of credentials Milewski and Callwood have as journalists, but I aspire to follow their lead. And I remind my own journalism students about why they chose the profession. I suggest that it’s not about personality, nor about getting it first, but definitely about trying to get it right. I cite H.L. Mencken, Fred Friendly, Betty Kennedy, Lotta Dempsey and my own father, Alex Barris, as models of the profession because they didn’t sit in meetings or at computers waiting for the stories to come to them. They left their offices behind, found unique sources, got them to talk and came back with the grist for stories, what the late New York Times reporter David Carr called “shoe-leather” journalism.

But back to Mark Bulgutch’s talk the other night – about the future of journalism, he’s not particularly optimistic.

“I’m not a fan of incessant opinion chatter on 24-hour news networks. I’m not a fan of cluttering the TV screen with ‘Breaking News’ banners hours after the news is broken.”

As an example, Bulgutch suggested that Canadians should fear what he called “iPhone journalism,” the notion that anybody with a smart phone is a journalist. Sitting in an interviewing theatre at the Burlington Public Library, the other night, he posed a hypothetical example of a fire suddenly breaking out nearby. He asked rhetorically if all those present could become a roomful of journalists covering the fire.

He said that, yes, they could become a roomful of witnesses, but unless they could interview witnesses, firefighters and paramedics – giving the fire a storyline and some context – they would remain just a roomful of witnesses.

“Reporters should go to where something is happening; they should see what is happening and then they should tell us what they saw,” he said.